Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook, has shifted its long-term strategy away from its social media apps to focus on the metaverse, a virtual world where people wearing augmented/virtual reality headsets can talk to each others’ avatars, play games, hold meetings, and otherwise engage in social activities.

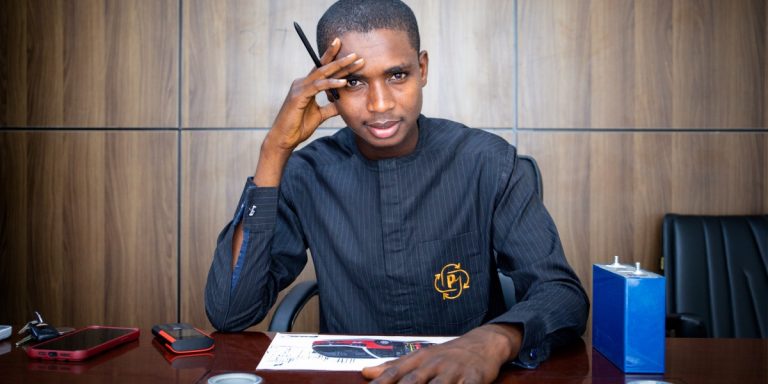

That’s created a lot of questions, such as what this means for a company that has been focused on social media for nearly two decades, whether Meta will be able to achieve its new goal of building a metaverse future, and what that future will look like for the billions of people who use Meta’s products every day. On Wednesday, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg revealed some answers during a keynote speech about the company’s latest developments in AI.

One of Meta’s main goals is to develop advanced voice assistant AI technology — think Alexa or Siri, but smarter — that the company plans to use in its AR/VR products, like its Quest headset (formerly Oculus), Portal smart display, and Ray-Ban smart glasses.

“The kinds of experiences you’ll have in the metaverse are beyond what’s possible today,” said Zuckerberg. “That’s going to require advances across a whole range of areas, from new hardware devices to software for building and exploring worlds. And the key to unlocking a lot of these advances is AI.”

The presentation comes during one of the most challenging moments in the company’s history. Meta’s share prices have taken a historic dip, its advertising model has been shaken up by Apple’s mobile privacy changes, and it faces the looming threat of political regulation.

So it makes sense that the company is looking to the future, in which Meta hopes to roll out sophisticated language-processing AI.

It’s the first time Meta has had an event solely dedicated to showcasing its AI developments, according to a Meta spokesperson. That being said, the company admits this AI is still in development and not widely used yet. The demonstrations are exploratory; Meta’s demo videos on Wednesday included disclaimers at the bottom that many of the images and examples are strictly for illustrative purposes and not actual products. Also: Avatars in the metaverse still don’t have legs.

If Meta is pushing its world-class computer science researchers to develop these tools, though, there’s a good chance it will succeed. And if fully realized, these technologies could change how we communicate, both in real life and in virtual reality. These developments also present significant privacy concerns about how more personal data collected from AI-powered wearable devices is stored and shared.

Here are a few things to know about how Meta is building out a voice assistant using new AI models, as well the privacy and ethical concerns an AI-superpowered metaverse raises.

Meta is building its own ambitious voice assistant for AR/VR

On Wednesday, it became clear that Meta sees voice assistants as a key part of the metaverse, and it knows that its voice assistant needs to be more conversational than what we have now. For example, most voice assistants can easily answer the question, “What’s the weather today?” But if you ask a follow-up question, such as, “Is it hotter than it was last week?” the voice assistant will likely be stumped.

Meta wants its voice assistant to be better at picking up contextual clues in conversations, along with other data points that it can collect about our physical body, like our gaze, facial expressions, and hand gestures.

“To support true world creation and exploration, we need to advance beyond the current state of the art for smart assistants,” said Zuckerberg on Wednesday.

While Meta’s Big Tech competitors — Amazon, Apple, and Google — already have popular voice assistant products, either on mobile or as standalone hardware like Alexa, Meta doesn’t (aside from some limited voice command functionality on its Ray-Bans, Oculus, and Portal devices).

“When we have glasses on our faces, that will be the first time an AI system will be able to really see the world from our perspective — see what we see, hear what we hear, and more,” said Zuckerberg. “So the ability and expectation we have for AI systems will be much higher.”

To meet those expectations, the company says it’s been developing a project called CAIRaoke, a self-learning AI neural model (that’s a statistical model based on biological networks in the human brain) to power its voice assistant. This model uses “self-supervised learning,” meaning that rather than being trained on large datasets the way many other AI models are, the AI can essentially teach itself.

“Before, all the blocks were built separately, and then you sort of glued them together,” Meta’s managing director of AI research, Joëlle Pineau, told Recode. “As we move to self-supervised learning, we have the ability to learn the whole conversation.”

As one example of how this technology can be applied, Zuckerberg — in virtual reality avatar form — demoed a tool the company is working on called “BuilderBot” that allows you to speak out what you want to see in your virtual reality. For instance, saying “I want to see a palm tree over there” could make an AI-generated palm tree pop up where you want, based on what you say, your gaze, your controllers/hands, and general contextual awareness, according to the company.

Meta still needs to do more research for this to be possible, and it’s studying what’s called “egocentric perception,” which is about understanding worlds from a first-person perspective, to build this out. Currently, it’s testing the technology from the model in its Portal smart displays.

Eventually, the company also hopes to be able to capture inputs beyond speech — like a user’s movement, position, and body language, to build even smarter virtual assistants that can anticipate what users want.

AI in the metaverse will present ethical challenges

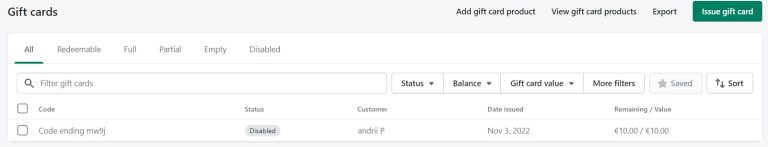

Privacy concerns and failures have haunted Meta and other big tech companies because their business models are built around collecting users’ data: our browsing histories, interests, personal communications, and more.

Those concerns are even greater, privacy experts say, with AR/VR, because it can track even more sensitive data, like our eye movements, facial expressions, and body language.

Some AR/VR and AI ethicists are worried about just how personal these data inputs can become, what kind of predictions AI can make with those inputs, and how that data will be shared.

“Eye-tracking data, gaze data, literally being able to quantify whether you’re feeling stimuli off of sexual arousal or a loving gaze — all of that is concerning,” said Kavya Pearlman, founder of the XR Safety Initiative, a nonprofit that advocates for the ethical development of technologies like VR. “Who has access to this data? What are they doing with this data?”

For now, the answers to those questions aren’t entirely clear, although Meta is saying it’s committed to addressing such concerns.

Zuckerberg said that the company is working with human rights, civil rights, and privacy experts to build “systems grounded in fairness, respect, and human dignity.”

But given the company’s track record of privacy breaches, some technology ethicists are skeptical.

“From a purely scientific perspective, I’m really excited. But because it is Meta, I’m scared,” said Pearlman.

In response to people’s concerns about privacy in the metaverse, Meta’s Pineau said that by giving users control over what data they share, the company can help alleviate people’s worries.

“People are willing to share information when there’s value that they derive out of that. And so if you look at it, the notion of autonomy, control, and transparency is what really allows the users to have more control over how their data is used,” she said.

Aside from privacy concerns, some Meta AR/VR users worry that if an AI-powered metaverse takes off, it may not be accessible to and safe for everyone. Already, some women have complained about encountering sexual harassment in the metaverse, such as when a beta tester of Meta’s social VR app Horizon Worlds reported being virtually groped by other users. Meta has since instituted what amounts to a 4-foot virtual safety bubble around avatars to help avoid “unwanted interactions.”

If Meta reaches its goal of using AI to make its AR/VR environments even more immersive and seamless in our daily lives, more problems around accessibility, safety, and discrimination are likely to surface. And though Facebook says it’s thinking about these concerns at the outset, its track record with its other products isn’t reassuring.