The audio chat app Clubhouse is built for two types of people: the talkers and the listeners. Tesla founder Elon Musk is a talker. So is Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. Robinhood’s Vlad Tenev is a talker, as are many other influential Silicon Valley figures, like investors Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen, who have staked millions of dollars into Clubhouse’s success. A regular user can be a talker too, although there’s no promise anyone (besides a few friends) will show up and stick around.

As a listener, though, the app offers a smorgasbord of chatrooms on virtually any topic you can think of: foreign language practice, wealth management, Instagram marketing tips, therapy, a 24/7 lo-fi music streaming service. Toggling between public rooms on the homepage is simple: A listener can quietly drop, already muted, into rows of audience members and tune into the unfolding conversation.

The catch to Clubhouse is that it’s invite-only, at least in its current beta-testing phase. People have to receive an invitation from an existing user to unlock access to the platform, which is only available for download through the iOS App Store. (Clubhouse’s founders say they are working to scale the app for a general audience, including Android users, but their expansion timeline remains uncertain.)

Despite these built-in functions geared toward exclusivity, the app carries significant potential for growth. Each new user is given four invites to hand out, and already there is an online marketplace for buyers and bidders eager to pay for one. More regular people — including international audiences across Europe and Asia — are now seeking entry following Elon Musk’s live talk on January 31, which maxed out the platform’s 5,000-person chat room capacity. Since then, Clubhouse has surpassed 3 million downloads, with an estimated user base of more than 2 million.

These statistics are a promising sign for the fledgling audio platform, which was launched in March 2020. Influential entrepreneurs and venture capitalists are bullish on crowning Clubhouse the next major social network; it’s reportedly valued at $1 billion after its latest round of funding.

The adoring hype from the tech world, however, has yet to reach most average Americans, who are less likely to be familiar with the platform since access is so limited. To put it into context, at 2 million users, Clubhouse is much smaller than behemoths like Facebook (2.8 billion global monthly active users, including Instagram and WhatsApp, which it owns), TikTok (1 billion), Twitter (330 million), and Snapchat (249 million).

The app’s invite-only system could’ve siloed its burgeoning popularity within certain social circles, but exclusivity became crucial in cultivating general intrigue. Celebrities, Black creatives, and entertainers, for example, were early adopters of the app. So were Silicon Valley insiders, spurred by investor interest. The app’s most vocal converts believe Clubhouse is the future of audio-driven social media, once it becomes accessible to the public. Yet, the platform has not been immune to complaints of harassment, misinformation, and feeble content moderation that have afflicted the biggest social networks. Users are aware of these flaws, but for now, Clubhouse’s novelty has yet to fade.

What is Clubhouse, and how does it work?

Clubhouse is the brainchild of founders Rohan Seth and Paul Davison, who previously collaborated on Talkshow, a now-defunct app that allowed users to have a public text conversation that any number of people could view. Clubhouse was their “last try,” they claim, at building a social app that aimed to be “more human” and driven by conversations, rather than posts.

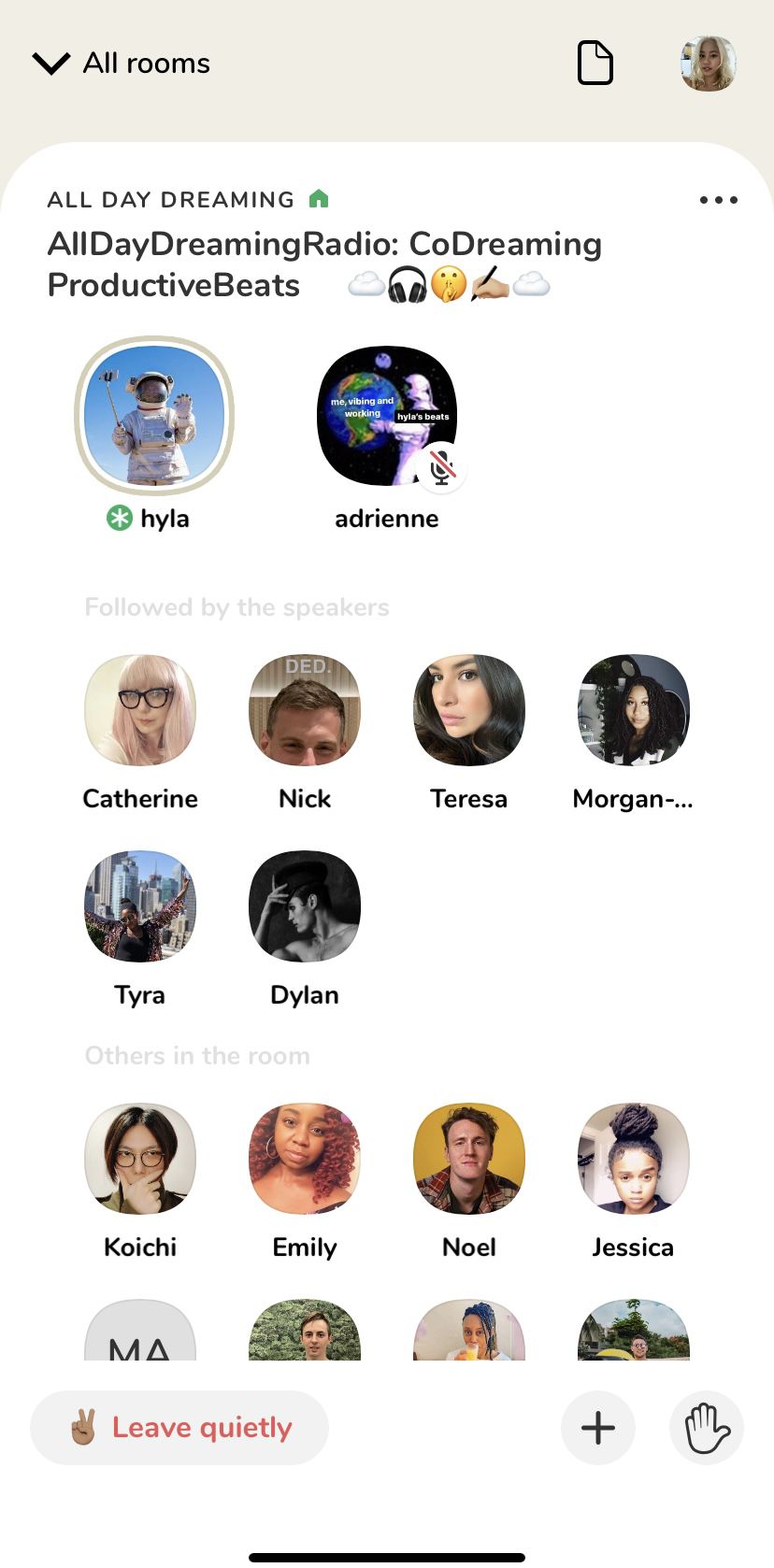

Speaking events on the app are set in rooms, which are organized into a sort of virtual stage. The host and moderators — who are given prerogative to speak — control the flow of conversation, who gets to speak, and when. As a listener, you can use the “raise your hand” function, but the moderator is in charge of handing over the digital microphone, if they choose to. If you’re followed by the moderator or host, your avatar will be “seated” in a special section above general audience members, which makes chiming in much easier. And whereas these chatrooms are temporary one-offs, users can also join public and private clubs, which are loosely categorized into categories like “technology” or “wellness,” that frequently update their schedule of upcoming events.

Vulture’s Craig Jenkins likened the app to “a never-ending trade convention … where the best time is had when you sneak off elsewhere with friends.” The experience on Clubhouse varies by room and subject matter, and can be comparable to tuning into an unedited podcast, an industry-specific panel, or a gossipy conference call. Like most social platforms (and professional conventions), Clubhouse is what you make of it and, ultimately, who you know. It’s also worth noting that the app is inaccessible to deaf people, and has yet to offer any sort of automatic captioning function.

There is a veneer of professionalism from the get-go, even for general users. Popular hosts and speakers tend to have some level of social or professional clout, and large rooms are usually led by established creatives, investors, or entrepreneurs. There are spaces that are more entertaining, informational, or scandalous than others (users have unwittingly stumbled upon NSFW “moan rooms”), but the burden of discovery typically falls on the user. Unlike a platform like TikTok, which heavily relies on algorithmic prodding, Clubhouse is a simulation of existing social hierarchies, which sequesters people into communities they’re already familiar with. The app also encourages the use of full names, rather than usernames, thereby relying on existing threads of recognition to draw in listeners.

Tech reporter Will Oremus argued that Clubhouse is the antithesis of Twitter based on how its social networks are assembled. “The structure of Twitter’s platform is essentially flat and open,” Oremus wrote, “in the sense that pretty much anyone can join, tweet, reply to anyone else, and have at least a remote chance to reach a massive audience.” Meanwhile, Clubhouse is more hierarchical and closed, even by predicating its early model on invitation.

The appeal — and troubling reality — of hosting open conversations

Authentic, nuanced conversation is billed as Clubhouse’s main appeal. Its founders believe that providing space for discussion can “bring people together” and effectively shatter the algorithmic echo chambers perpetuated by most popular platforms. A Bloomberg opinion article in December praised the app for its “niceness” and ability to “restore peaceful discourse and civility rather than exacerbate tensions.”

In early February, Clubhouse made international headlines as Chinese, Taiwanese, Hong Kong, and Uighur users discussed topics that are prohibited in China, like the concentration camps in Xinjiang, garnering thousands of listeners. China soon blocked the app, but the rare instance of cross-border dialogue provided an optimistic pretense for the platform’s lofty goal: becoming the go-to public forum for global conversations and ideas.

Clubhouse now blocked in China.

The audio drop-in startup was rapidly gaining steam in China last week, the invitation-only US app allows users to listen to discussions n interviews in conference-call style online rooms, attracting users to conversations on a wide range of topics pic.twitter.com/gHKDwkLVUp— Eva 郑 عائشة (@evazhengll) February 8, 2021

The concept is intriguing, and big platforms are eyeing Clubhouse’s ascent. Twitter has hopped on the bandwagon by testing a similar chatroom-like feature called Spaces, and Facebook is rumored to be building a competing product. Yet, Clubhouse’s current format is purposefully limiting, even as more users join the platform. Conversation tends to remain civil — and arguably insulated — due to the level of control hosts and moderators can have over a room, down to who’s able to listen in. A moderator is intended to serve as a sort of micro-gatekeeper or community manager.

Still, some critics are concerned about the possibility of institutional exclusion, and how existing biases are reinforced in the chatroom. On Twitter, the Information’s Jessica Lessin and New York Times’s Taylor Lorenz have argued that certain high-profile guests and hosts have a history of blocking journalists, notably women, which prevents reporters from listening in on potentially newsworthy Clubhouse conversations and shows.

Then there’s the issue of moderation. Self-appointed moderators are not always equipped to handle issues like harassment, hate speech, or misinformation, and Clubhouse has yet to implement guardrails to curtail such behavior. (Users on the app can report harassment or speech that violates community guidelines, but there’s currently little by way of moderation tools available.) In September, a three-hour discussion on anti-Semitism in Black communities eventually devolved into anti-Semitic comments, which frustrated Jewish users who felt the event should’ve been more actively moderated. Critics are wary of the app’s tolerance for casual racism and misogyny; writer Nikki Onafuye recently wrote of how Clubhouse amplifies the toxic interactions Black women experience in their daily lives.

Enters @joinClubhouse. Hears: 1) Non-Jewish folks redefining “antisemitism”, 2) Jews are the face of capitalism, 3) Jews are “weaponizing antisemitism”, 4) Non-Jews asking Jews to tap into unlimited emotional labor to educate. I’m DONE.

— michaela (@MichaelaHirsh) September 29, 2020

The rampant racism, misogyny, and disinformation that plague major social platforms will doubtless migrate to Clubhouse as it gains more users. There are few available models of moderation on a chat app, however. The challenge lies in how interactions are ephemeral, unless a user records a conversation (an act that violates community guidelines). Misbehavior and disinformation can be difficult to document, and so far, complaints and controversy are usually relitigated on Twitter. There is also scrutiny as to who is allowed on the app. Far-right political figures like Roger Stone and Mike Cernovich are on the platform and building audiences, and some users are unhappy that alleged assaulters, like Tory Lanez and Russell Simmons, are participating in chats.

Some skeptics are turned off by Clubhouse’s appeal to a certain type of user, namely the talkers — those who are extroverted, eager to learn, or interested in knowledge-sharing. “Clubhouse is the Linkedin newsfeed with audio,” joked one Twitter user. While those aren’t necessarily bad traits, having too many extroverted talkers could lead to unengaging or self-involved conversations, much like an off-topic conference call. According to the Information’s Sam Lessin, Clubhouse reproduces “the idle chatter of people in the real world,” which leads to lower-quality per-minute content than curated media. But real-life conversations also depend on factors like body language, eye contact, and other visual cues that involve both speaker and listener, none of which have, as yet, been replicated on the app.

Clubhouse plans to invest in influencers, but a post-pandemic world could test users’ interest

Audio-only media, such as podcasts or radio shows, tend to be highly scripted or narrative-driven with specific time allotments to keep listeners interested. On Clubhouse, the freewheeling conversations are the exact opposite. The reason to tune in, according to Sam Lessin, “is not for content but for who is speaking.” A major celebrity or politician could drive a burst of traffic to Clubhouse, but unless there’s a devoted base of long-term users, that could pose a problem for the app’s future.

The company has expressed interest in investing in its creators by launching features like tipping, tickets, and subscriptions. The New York Times reported that Clubhouse is testing an invite-only creator pilot program with more than 40 influencers, some of whom host popular shows on the platform. This financial investment suggests that Clubhouse hopes to bolster its creators as unique personalities who could retain and grow audiences.

But can the app be sustainable by investing in talkers, and trusting that regular users — the listeners — will regularly tune in? Clubhouse has, perhaps, unlocked a late-stage pandemic sense of unfettered FOMO, a feeling that’s been exacerbated by the lockdown. After nearly a year without the comforting routine of daily life, the internet has become many people’s crucial conduit for social interaction. Suddenly, an invite-only app comes along that allows major celebrities and out-of-reach personalities to casually converse with regular people. The idea might sound enticing to our gossip-starved ears. Now that the party has moved online, what else is there to do besides listen?