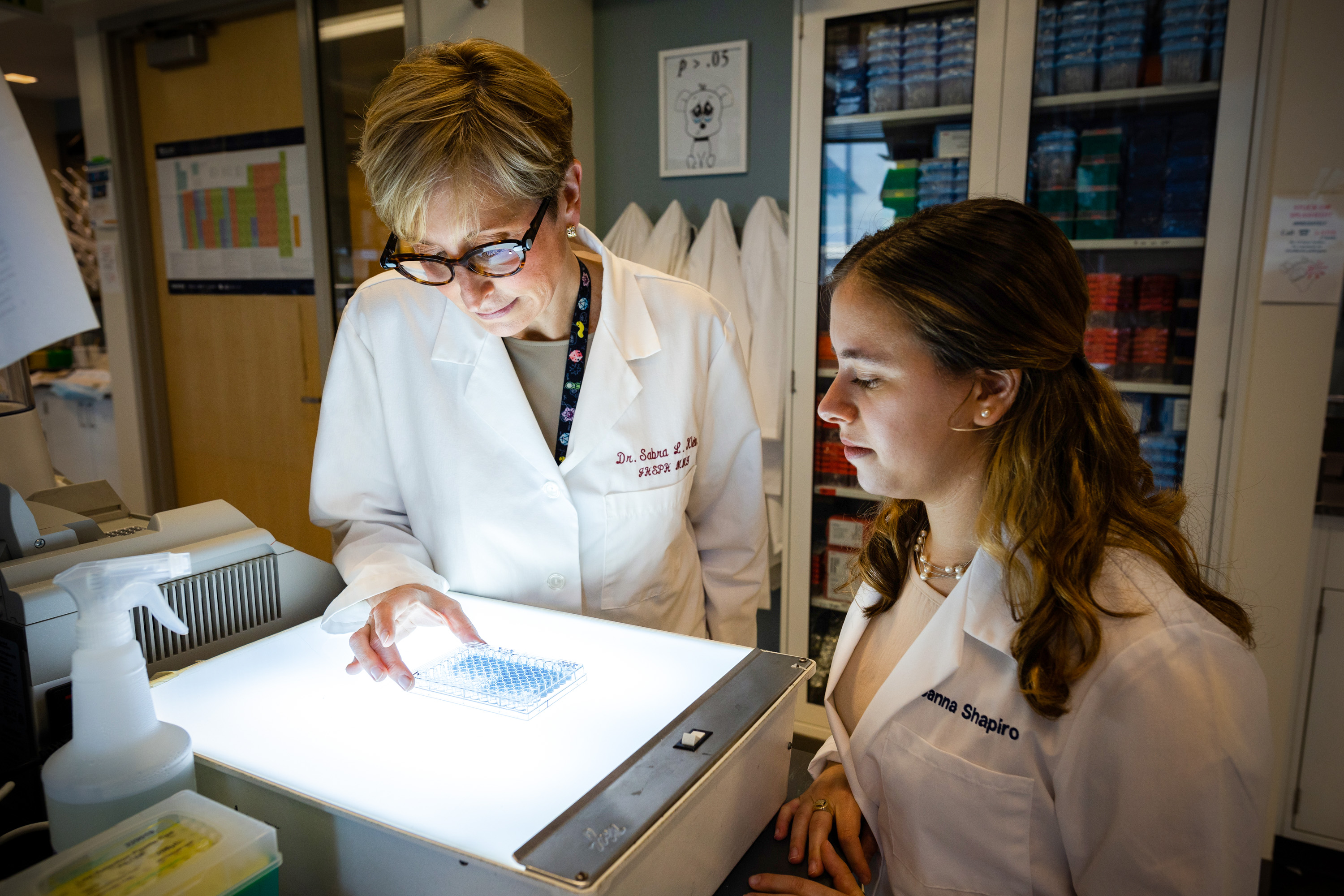

She ultimately found a postdoctoral position in the lab of one of her thesis committee members. And in the years since, as she has established a lab of her own at the university’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, she has painstakingly made the case that sex—defined by biological attributes such as our sex chromosomes, sex hormones, and reproductive tissues—really does influence immune responses.

Through research in animal models and humans, Klein and others have shown how and why male and female immune systems respond differently to the flu virus, HIV, and certain cancer therapies, and why most women receive greater protection from vaccines but are also more likely to get severe asthma and autoimmune disorders (something that had been known but not attributed specifically to immune differences). “Work from her laboratory has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of vaccine responses and immune function on males and females,” says immunologist Dawn Newcomb of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. (When referring to people in this article, “male” is used as a shorthand for people with XY chromosomes, a penis, and testicles, and who go through a testosterone-dominated puberty, and “female” is used as a shorthand for people with XX chromosomes and a vulva, and who go through an estrogen-dominated puberty.)

Through her research, as well as the unglamorous labor of arranging symposia and meetings, Klein has helped spearhead a shift in immunology, a field that long thought sex differences didn’t matter. Historically, most trials enrolled only males, resulting in uncounted—and likely uncountable—consequences for public health and medicine. The practice has, for example, caused women to be denied a potentially lifesaving HIV therapy and left them likely to endure worse side effects from drugs and vaccines when given the same dose as men.

Men and women don’t experience infectious or autoimmune diseases in the same way. Women are nine times more likely to get lupus than men, and they have been hospitalized at higher rates for some flu strains. Meanwhile, men are significantly more likely to get tuberculosis and to die of covid-19 than women.

In the 1990s, scientists often attributed such differences to gender rather than sex—to norms, roles, relationships, behaviors, and other sociocultural factors as opposed to biological differences in the immune system.

For example, even though three times as many women have multiple sclerosis as men, immunologists in the 1990s ignored the idea that this difference could have a biological basis, says Rhonda Voskuhl, a neuroimmunologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “People would say, ‘Oh, the women just complain more—they’re kind of hysterical,’” Voskuhl says. “You had to convince people that it wasn’t just all subjective or environmental, that it was basic biology. So it was an uphill battle.”

ROSEM MORTON

Despite a historical practice of “bikini medicine”—the notion that there are no major differences between the sexes outside the parts that fit under a bikini—we now know that whether you’re looking at your metabolism, heart, or immune system, both biological sex differences and sociocultural gender differences exist. And they both play a role in susceptibility to diseases. For instance, men’s greater propensity to tuberculosis—they are almost twice as likely to get it as women—may be attributed partly to differences in their immune responses and partly to the fact that men are more likely to smoke and to work in mining or construction jobs that expose them to toxic substances, which can impair the lungs’ immune defenses.

How to tease apart the effects of sex and gender? That’s where animal models come in. “Gender is a social construct that we associate with humans, so animals do not have a gender,” says Chyren Hunter, associate director for basic and translational research at the US National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health. Seeing the same effect in both animal models and humans is a good starting point for finding out whether an immune response is modulated by sex.