Arc, a visual artist from Saudi Arabia, was initially skeptical of how cryptocurrency could be adopted in the art world. He didn’t know much about the technology and was doubtful of its reputation. Last year, a representative from KnownOrigin, a digital art marketplace powered on the Ethereum blockchain, approached Arc on Twitter and he agreed to give the platform a try. The representative helped him set up an artist account and a cryptocurrency wallet, and covered the “gas” fees Arc paid in order to upload and “mint” his artwork on the blockchain.

“I started posting on KnownOrigin without knowing what I was doing at all and just experimenting,” Arc told me. “A few days later, I got a notification that one of my pieces sold. I was really shocked because I wasn’t used to the idea of people buying my digital art.”

As of March 2021, Arc has sold more than 270 pieces in the form of non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, with a total value of over $480,000. That amount, he added, is based on current pricing of the cryptocurrency Ethereum, which has increased in value since he began selling his work. Arc is far from the only artist riding the coattails of the lucrative NFT craze. The artist behind Nyan Cat, Chris Torres, sold the tokenized version of the GIF for $590,000 in late February. Digital artist Mike Winkelmann, also known as Beeple, recently sold a $6.6 million video artwork on Nifty Gateway, a virtual marketplace for NFTs. His collage “The First 5,000 Days” is currently up for auction at Christie’s until March 11 and will be the first purely digital work sold as an NFT by a major auction house. Winkelmann will also earn a 10 percent royalty off each consequent resale of his art.

The hype around these digital collectibles is not exclusive to the art world. Independent artists and musicians are championing NFTs as a viable model of digital ownership. Meanwhile, sports, music, gaming, and other fan-driven industries are recognizing the technology’s potential as a burgeoning revenue stream. The NBA launched Top Shot in 2019, a marketplace for NBA highlight reels, which users can collect and trade through blockchain technology. It has since generated over $230 million in sales, with individual clips of LeBron James and Zion Williamson selling for about $200,000 each. Last month, YouTuber Logan Paul sold more than $5 million worth of NFTs, in the form of digital Pokémon cards featuring a cartoon image of Paul. And electronic music producer 3LAU dropped a limited-edition NFT-based album on February 27, generating over $11.6 million in less than 24 hours.

So, what are non-fungible tokens?

These prices might sound mind-boggling, and for the average person, the technical jargon surrounding NFTs is likely confusing or intimidating. Rest assured, you don’t have to be an expert in blockchain technology to understand, purchase, or even create NFTs. Still, getting your hands on an NFT can be more costly and environmentally damaging than one might expect for a digital product. These tokens are based on the economic concept of fungibility, which the Oxford Dictionary defines as the ability “to replace or be replaced by another identical item,” or to be “mutually interchangeable.” Currency is a fungible asset, as are oil and gold.

Non-fungible digital assets are unique goods that don’t have interchangeable value. That definition might seem abstract, but these kinds of assets have existed since the early days of the internet, according to Devin Finzer, CEO of the NFT marketplace Open Sea. “Domain names, event tickets, in-game items, even handles on social networks like Twitter or Facebook, are all non-fungible digital assets,” Finzer wrote in an exhaustive explainer on NFTs. “They just vary in their tradeability, liquidity, and interoperability.”

So what transforms an asset into a non-fungible token? Digital marketplaces like Open Sea and Known Origin have simplified the process for users who don’t want to get in the weeds of blockchain technology. (There is no universal definition of a blockchain, which can be confusing. For the purposes of this article, think of blockchain as “a sequence of records shared among a network, that are both accessible and immutable, meaning no member can change or delete the data within them without invalidating the rest of the sequence.”)

Artists and creators can upload and certify, or “mint,” any digital asset — 3D animations, video clips, tweets, music — on the Ethereum blockchain. This process codifies the NFT, establishing a verifiable record of price, ownership, and transference, and prevents the file from being digitally forged or replicated. Once it’s uploaded, the NFT will exist permanently on the blockchain, so long as the chain remains in operation. As a result, no two NFTs are purely identical, since each piece contains unique digital properties. Even if an artist publishes two artworks with no clear physical distinctions, the metadata encoded in each NFT is different. NFTs have yet to fully protect intellectual property, however; artists must still register copyrights for their work if they ever need to take legal action against counterfeiters.

Digital artists like Arc are drawn to the technology’s ability to confer uniqueness, permanence, and proof of provenance. Artists and musicians have historically relied on middlemen — auction houses, galleries, and streaming platforms — to sell or host their work. In some cases, they don’t earn royalties from future sales. With NFTs, artists can ensure that they receive a predetermined share of royalties (usually 10 percent) from sales on the secondary market.

“The NFT space feels like it’s set up for the artist,” said Victor, an 18-year-old visual artist who works under the moniker FEWOCiOUS. “Before I began selling NFTs, I knew very little about the art industry and problems with receiving royalties. I don’t know what the future holds, but I think NFTs will become a standard for selling art.”

The emerging market for NFTs is driven by novelty and digital scarcity

For artists and ardent collectors, purchasing and trading one-of-a-kind NFTs can be a means of creative support. There is an inherent feeling of community, Victor added, since the technology has been part of a niche subculture that is only beginning to enter the mainstream. Granted, this isn’t the first time NFTs have captured broad attention: In 2017, CryptoKitties, a blockchain-based game where players breed and trade digital cats, made headlines for generating over $1 million in virtual kitten sales.

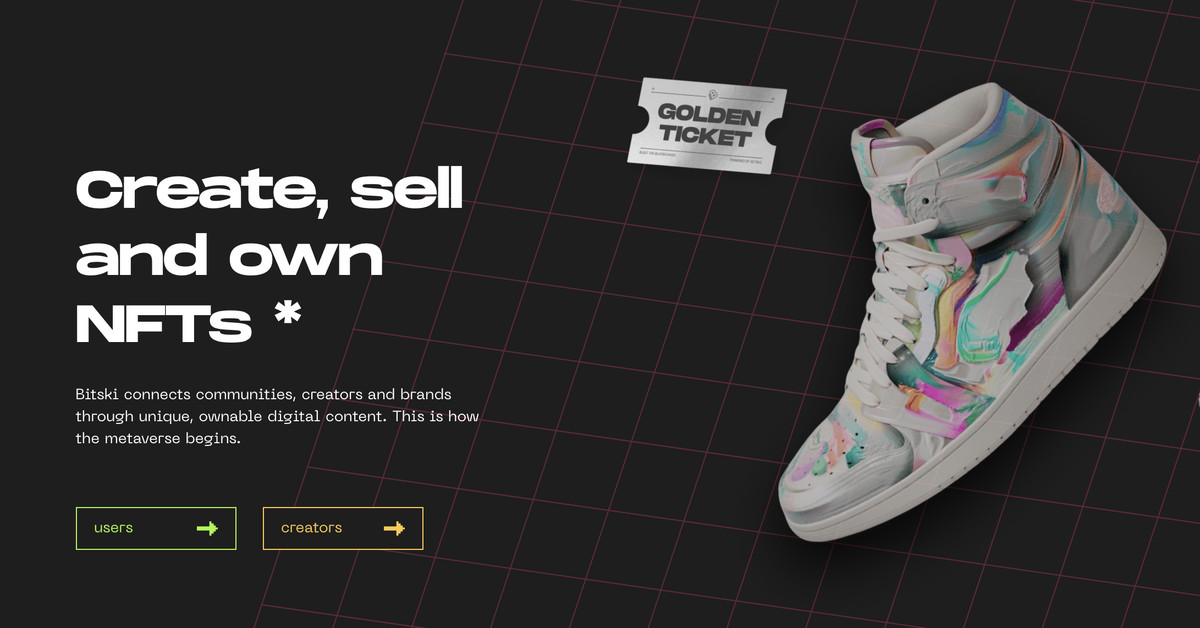

That interest in cryptocollectibles changed what people thought blockchain could be used for, said Donnie Dinch, CEO of Bitski, a Shopify-like storefront for creators to list and sell their NFTs. “Digital ownership, prior to NFTs, is sort of fraudulent and nonexistent,” he told me. “You don’t own anything. There are people trying to sell their Fortnite accounts on Poshmark.” Dinch launched Bitski in 2018 as the “Venmo for cryptocurrency,” but began expanding the platform into a storefront for NFTs last year after meeting with creators who were interested in selling their own tokens.

Most NFT marketplaces operate on the Ethereum blockchain and require potential buyers to have an existing cryptocurrency wallet. Bitski is one of the few platforms that allows users to make transactions with a credit card, something Dinch thinks will be more common as NFTs enter the mainstream. “Crypto shouldn’t be a barrier for participating in the NFT space,” he said. “The reason we’ve gotten away with digital ownership as it currently exists is probably because there hasn’t been a tech platform to solve that issue.”

Some onlookers are concerned by the huge sums of money being pumped into NFTs, and critics see this concern as a side effect of the speculative nature of cryptocurrency. Bitcoin, for example, is notoriously volatile, and has experienced sudden booms and crashes since 2013. Ethereum, the cryptocurrency that most NFTs are purchased with, catapulted to an all-time high in early February, only to sharply fall by the end of the month. Due to these fluctuating metrics, some have dismissed NFTs as a viral fad, while its loudest champions remain convinced it has the potential to change the future of digital ownership and creative patronage.

One of the most confusing things, for some, is the problem that these digital assets sometimes exist in forms that are readily and freely available to others. Billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban compared his ownership of NBA Top Shot reels to his pastime hobby of collecting stamps and baseball cards. “Some people might complain that I can get the same video [of Maxi Klieber dunking] on the Internet anywhere any time and watch it,” he wrote. “Well guess what, I can get the same picture on any traditional, physical card on the internet and print it out, and that doesn’t change the value of the [actual] card.” Digital goods, Cuban argued, are just as valuable as tangible physical goods, and operate on the same economic principles of supply and demand.

In a way, NFTs seem almost counterintuitive to the digital media age, in which images, videos, sounds, and text can be easily replicated and shared. The technology aims to codify — and enforce — a metric of scarcity that is at odds with the concept of an open internet. This scarcity can theoretically be a good thing; it benefits the creator and the buyer of the artifact. It does, however, take massive amounts of energy to construct and maintain.

Transactions on the Ethereum blockchain are incredibly energy inefficient; one transaction uses more power than the average US household does in a day, according to the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. For years, Ethereum developers have planned to move the blockchain to a different operating model, called proof of stake, which will be less energy-intensive. Still, energy inefficiency — and the novelty factor driving up the price of NFTs — is worrisome to some artists and cryptocurrency critics.

The most vocal crypto advocates — venture capitalists, celebrities, and popular creators — believe NFTs can “democratize art” and creative patronage at large. The technology could theoretically drive the growth of the “creator economy” — a term that describes a growing class of freelance artists and creatives who earn income by distributing and monetizing content on social platforms. But as music writer Arielle Gordon wrote for Stereogum, in their current iteration, NFTs appear to be “tremendously efficient at replicating the most inaccessible paradigms” of the art world, despite the “decentralized, supposedly more democratic nature” of blockchain. There is a hierarchy of creators, and established celebrities and musicians benefit from existing social structures (the musician and artist Grimes recently sold over $6 million worth of digital art on Nifty Gateway).

Thus, the system “theoretically encourages investors to seek out undiscovered talents,” Gordon concluded, “treating artists almost like stock, to be consumed at their lowest possible value to be cashed in after they’ve achieved mass popularity.” This is no different from the art world, which is sustained on whether an artist or artwork will appreciate in value. NFT marketplaces are replicating the auction process for their most coveted pieces, some of which are put to bid again on the secondary market. Of course, paying and bidding exorbitant prices for rare collectible items is not a new phenomenon; there are entire markets of vintage and limited-release goods sustained by the pockets of wealthy people. For now, at least, the space appears to be primarily populated by tech-adjacent buyers with thousands of dollars to spend on Ethereum-based art.

Dinch, the CEO of Bitski, admitted that there is an element of novelty that’s driving some of the extreme pricing. However, he believes the utility of NFTs will extend far beyond a secondary resale market. “The way we’re perceiving this technology is like we’re dealing with web pages in 1996,” he said. “We’re excited to own a unique picture. Not to go all Ready Player One, but it seems inevitable that people will want the means to express and represent themselves, their aesthetics, in the digital space.”