Six years ago, the media heralded Elizabeth Holmes as the next Steve Jobs or Bill Gates. Now, the former CEO of the shuttered blood-testing startup Theranos is on trial for 12 counts of fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud. But the collapse of the company and the indictment of its controversial founder haven’t caused much soul-searching in Silicon Valley. At the same time, it’s unclear if Washington has made the necessary changes to ensure that a company like Theranos doesn’t market defective tests to the public again.

Theranos’s ultimate goal, a printer-sized machine that required only a drop of blood and could process hundreds of blood tests in pharmacies across the country, was always lofty. But in 2018, federal prosecutors accused Holmes of intentionally misleading investors and running faulty tests on patients’ blood samples to fuel her own financial success. Holmes’s lawyers insist that the 37-year-old Stanford dropout truly believed in her company but made “mistakes” in her otherwise noble mission to make faster, cheaper blood-testing. Her legal team is also expected to argue that, while CEO, Holmes was abused by her former partner and former Theranos chief operating officer Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, whose separate trial is scheduled to begin next year.

“This is a case about fraud, about lying and cheating to get money,” Assistant US Attorney Robert Leach said in his opening statements on Wednesday. “It’s a crime on Main Street, and it’s a crime in Silicon Valley.”

While there’s a lot at stake for Holmes, who faces up to 20 years in prison, Silicon Valley doesn’t seem fazed by the trial or concerned about its outcome. Theranos, though inspired by its culture, was not backed by major venture capital firms from the tech industry. Meanwhile, a regulatory gap that allowed companies like Theranos to roll out its tests to patients hasn’t been closed, and amid the pandemic, the FDA is worried that some unapproved diagnostic tests are being used with “limited assurance” that they work.

“First off, hope springs eternal,” Lawton Burns, a health care management professor at Wharton, told Recode. “There is so much money in VC land, and they gotta park it somewhere. And some of the traditional places where they’ve parked it — in, like, Big Tech — those things have gotten saturated, so they had to look for some other place to park it.”

In funding conversations, Theranos is not a major topic these days, according to the Wall Street Journal. While some investors — especially those without health care experience — may be paying more attention to data, there’s no sign that Theranos has broadly changed how investors choose companies to fund, or how those companies approach sharing research. For example, Theranos notoriously kept its data and machine under wraps, citing “trade secrets,” a practice that critics say the company used to cover up fraud and hide shoddy science. But a study published in the European Journal of Clinical Investigation from researchers at Stanford found that most health care companies valued over $1 billion, as of 2017, aren’t publishing much peer-reviewed research.

Walgreens invested more than $140 million into Theranos, and in 2013, the companies announced they would enter a “long-term partnership” to bring Theranos tests into Walgreens pharmacies. Like individual investors, the company saw in Theranos a promising opportunity and the chance to get a leg up against its competitors. But by bringing Theranos machines into its stores without ever fully checking that the technology worked, Walgreens ultimately gave the company credibility. Some might say the companies complicity endangered the patients who used Theranos’s blood tests at their stores. Walgreens declined to comment on whether it had changed its approach.

Some see Holmes’s trial as a day of judgment for Silicon Valley culture and its reckless tendencies. (Phrases like “move fast and break things” and “fake it till you make it” sum up this sentiment.) Certain Silicon Valley leaders, however, have pushed back against the idea that Theranos represents their values at all. Veteran investor Paul Graham, for instance, has criticized the media for characterizing Theranos “as typical of Silicon Valley.” He said in a tweet that “people like Elizabeth Holmes are actually rarer there than in the rest of the business world, or in politics.”

Many of these critics point to the funding behind Theranos and the structure of its board as evidence that the company strays from the traditional Silicon Valley model. Typically, venture capital firms spend a significant amount of time, research, and expertise studying a company before investing in it, and want some proof of initial concept, like research results. More specifically, health care companies often recruit people with significant health care experience to serve on their boards of directors.

That’s not how Theranos worked. The company’s 12-person board was notably light on medical and tech experts. The board did, for some reason, include prominent national security leaders, including former Defense Secretary James Mattis and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Several of the company’s major investors, including former education secretary Betsy Devos, Rupert Murdoch, and members of the Walmart-owning Walton family, also had little medical experience.

Overall, Theranos was mainly propped up by investments from powerful individuals and family friends, not many venture capital funds, several of which actually passed on the chance to invest in the company.

“It was wealthy individuals, families, people who don’t spend basically every waking hour thinking about business models and problems and breakthroughs in health care,” Bryan Roberts, a partner at the venture capital firm Venrock who focuses on health care investment, told Recode. “In the sort of core early-stage venture investment community, I think there’s been zero impact.”

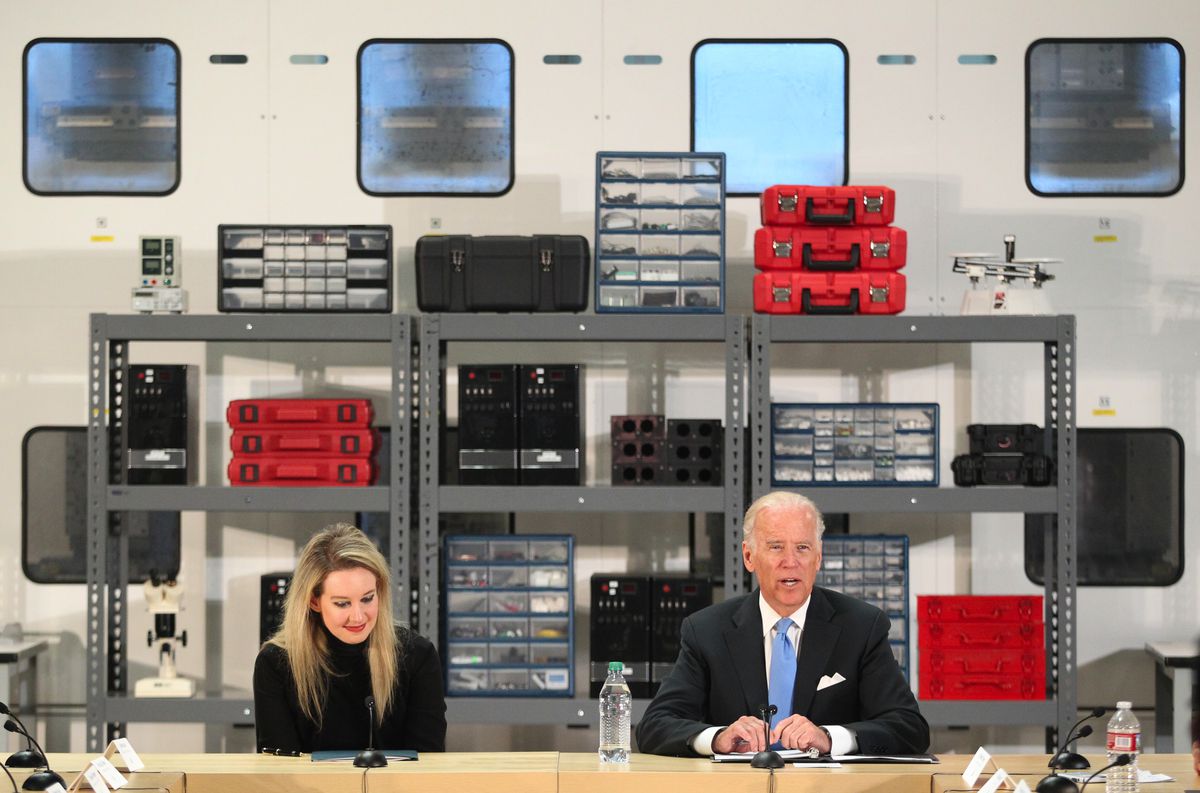

But even if Theranos was not directed and funded much like a Silicon Valley company, Holmes certainly wanted to emulate the “fake it till you make it” mentality that’s often linked to the tech industry. It is this approach that prosecutors now allege led to multiple counts of fraud, and she had support from some prominent tech leaders before her fall from grace.

Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison, who invested in the company, reportedly encouraged Holmes to ignore detractors, for example. Theranos, which was based in Palo Alto, also actively welcomed the association with Silicon Valley, with Holmes sitting down for interviews at tech conferences and even making a black turtleneck her daily uniform in what seemed like an obvious effort to emulate Steve Jobs.

“She is still, in my view, a child of this culture,” John Carreyrou, the former Wall Street Journal reporter who first exposed the problems with Theranos’s machines, recently told the Washington Post. “She surfed on this myth of the genius founder who can see around corners.”

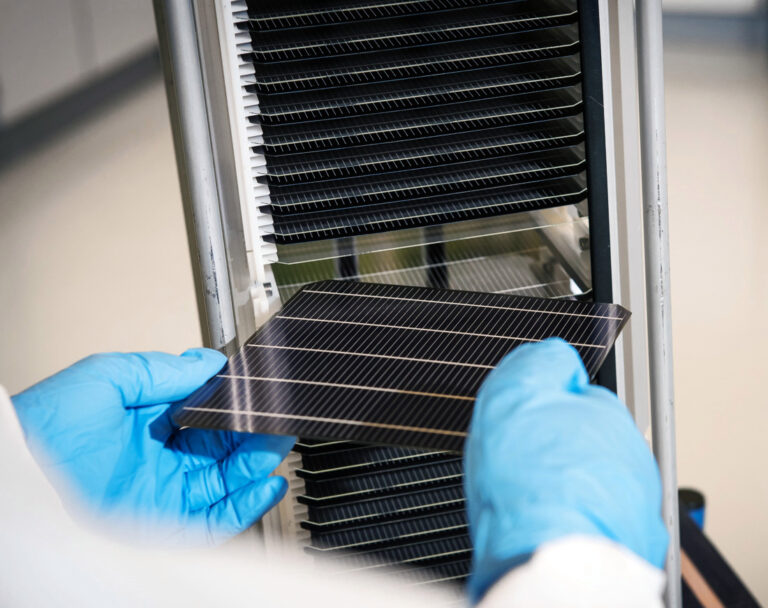

Despite Holmes’s settlement with the SEC and her and Balwani’s court cases, interest in innovative diagnostic testing and technology is only growing, thanks in part to the pandemic. Companies have raced to meet the demands of the pandemic with new Covid-19 tests, some of which have made their way to pharmacy shelves within the less than two years since the pandemic began.

Health startups raced to build their own Covid-19 tests and sell them directly to consumers in the early days of the pandemic. And while the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) took some time to authorize tests, especially at-home kits, the agency told Recode that it’s now issued over 400 emergency use authorizations for Covid-19 tests. Within health care investment overall, the diagnostics and biopharmaceutical sectors showed the largest growth since 2019, according to Silicon Valley Bank, a commercial bank often used by startups.

“Before the pandemic, there was just a lot of reluctance to fund diagnostics because so much of a company’s success is dependent upon whether reimbursement from payers or insurance companies is successfully achieved,” said Heather Bowerman, the founder and CEO of DotLab, which is working on a blood test for diagnosing endometriosis. “Now, there’s more of an appetite for just diagnostic fields overall.”

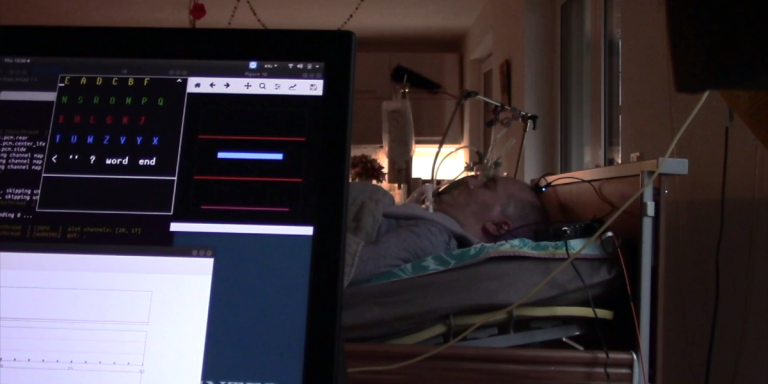

That doesn’t mean the FDA isn’t still concerned about lacking oversight for laboratory-developed tests, which are tests for biological samples that are designed and made in one single lab. Again, the loophole for lab-developed tests that Theranos and other companies have taken advantage of still exists. Last fall, the agency found that 82 of 125 requests for emergency use authorization lab-developed Covid-19 tests had issues with their design or validation process. Most of these were eventually fixed, but some weren’t authorized.

“We have been concerned since the 1990s, long before Theranos, that there are a significant number of unapproved laboratory-developed tests (LDT) being used with limited assurance that the tests works,” FDA spokesperson Lauren-Jei McCarthy told Recode. “Our experience with tests developed by labs for Covid-19 underscores the need for diagnostic reform.”

But despite the FDA’s call for change, the extent to which the agency has the power to provide oversight over these types of tests remains unclear.

We won’t get a verdict in the Holmes case for quite some time, as the trial is expected to last at least 13 weeks. But even if Holmes is found guilty, it’s not clear how well we’re set up to stop the next faulty diagnostic tool from making it to patients, especially as the pandemic continues on.