“Times must be good when a young biotech company can afford to hire people to write unrelated magazine-style articles,” snarked Dirk Haussecker, a savvy biotech stock picker who is active on Twitter.

Kelly says the magazine was inspired by Think, a periodical printed by IBM starting in the 1930s. “Why did they do that? Well, no one knew what the heck a computer was,” says Kelly, who sees Ginkgo playing a similar role as an evangelist for the possibilities of genetic engineering.

During a podcast, journalists with Stat News compared Ginkgo to a “meme stock,” or “stonk,” positioned to appeal to an investing public chasing trends without regard for business fundamentals. When the SPAC deal is finalized—sometime in September—the company is going to trade under the stock symbol “DNA,” once owned by Genentech, an early hero of the biotech scene. “Ginkgo Bioworks does not deserve to use the DNA ticker,” said Stat stock reporter Adam Feuerstein.

SPACs are a Wall Street trend that offers an IPO path with a little less than the usual scrutiny of a company’s financial outlook. Will Gornall, a business school professor at the University of British Columbia, believes that they democratize investor access to hot sectors but can also overestimate companies’ value. Some deals, like the one that took Richard Branson’s space company Virgin Galactic Holdings public, have done well, but five electric-car companies that went public via SPACs were subsequently pummeled with what Bloomberg called “brutal” corrections.

Gornall can see a bettor’s logic to the Ginkgo gamble. In recent years stock market profits have been driven by just a handful of tech companies, including Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft—each now worth more than a trillion dollars. “The valuation could make sense if there is even a 1% chance that biology is the computer of the future and this is the company that achieves that,” says Gornall.

Other people’s products

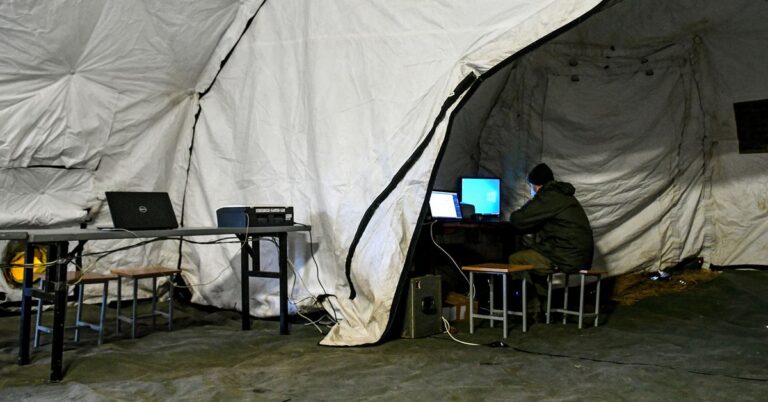

Since it was founded, Ginkgo has spent nearly half a billion dollars, much of it building labs equipped with robots, gene sequencers and sophisticated lab instruments such as mass spectrometers. These “foundries” allow it to test genes added to microorganisms (often yeast) or other cells. It claims it can create 50,000 different genetically modified cells in a single day. A typical aim of a foundry project is to assess which of hundreds of versions of a given gene is particularly good at, say, turning sugar into a specific chemical. Kelly says customers can use Ginkgo’s services instead of building their own lab.

What’s missing from Ginkgo’s story is any blockbuster products resulting from its research service. “If you are labeling yourself ‘synbio’, that is setting the bar high for success—you are saying you are going to the moon,” says Koeris. “You’ve raised so much money against a fantastic vision that soon you need to have a transformative product, whether a drug or some crazy industrial product.”

To date, Ginkgo’s engineering of yeast cells has led to commercial production of three fragrance molecules, Kelly says. Robert Weinstein, president and CEO of the US arm of the flavor and additives maker Robertet, confirmed that his company now ferments two such molecules using yeast engineered by Kelly’s company. One, gamma-decalactone, has a strong peach scent. The other, massoia lactone, is a clear liquid normally isolated from the bark of a tropical tree; used as flavoring, it can sell online for $1,200 a kilogram. Running a fermenter year-round could generate a few million dollars’ worth of such a specialty chemical.

GINGKO BIOWORKS

To George Church, a professor at Harvard Medical School, such products don’t yet live up to the promise that synthetic biology will widely transform manufacturing. “I think flavors and fragrances is very far from the vision that biology can make anything,” says Church. Kelly also sometimes struggles to reconcile the “disruptive” potential he sees for synthetic biology with what Ginkgo has achieved. Church drew my attention to a May report in the Boston Globe about Ginkgo’s merger with Soaring Eagle. In it, Kelly said his firm was an attractive investment because the world was becoming familiar with the extraordinary potential of synthetic biology, citing the covid-19 vaccines made from messenger RNA and the animal-free proteins in new plant burgers, like those from Impossible Foods.

“The article was a list of achievements, but the most interesting achievements were from others,” says Church. “It doesn’t seem to add up to $15 billion to me.” Still, Church says he hopes that Ginkgo does succeed. Not only is the company his “favorite unicorn,” but it acquired the remains of some of his own synthetic-bio startups after they went bust (he also recently sold a company to Zymergen). How Ginkgo performs in the future “could help our whole field or hurt our whole field,” he says.

While Ginkgo’s work has not led to any blockbusters, and Kelly allows it’s “frustrating” that biotech takes so long, he says products from other customers are coming soon. The Cannabis company Cronos, based in Canada, says by the end of the year it will be selling intoxicating pineapple-flavored candy containing CBG, a molecular component of the marijuana flower; Ginkgo helped show it how to make the compound in yeast. A spinout from Ginkgo, called Motif FoodWorks, says it expects to have a synthetically produced meat flavor available this year as well.