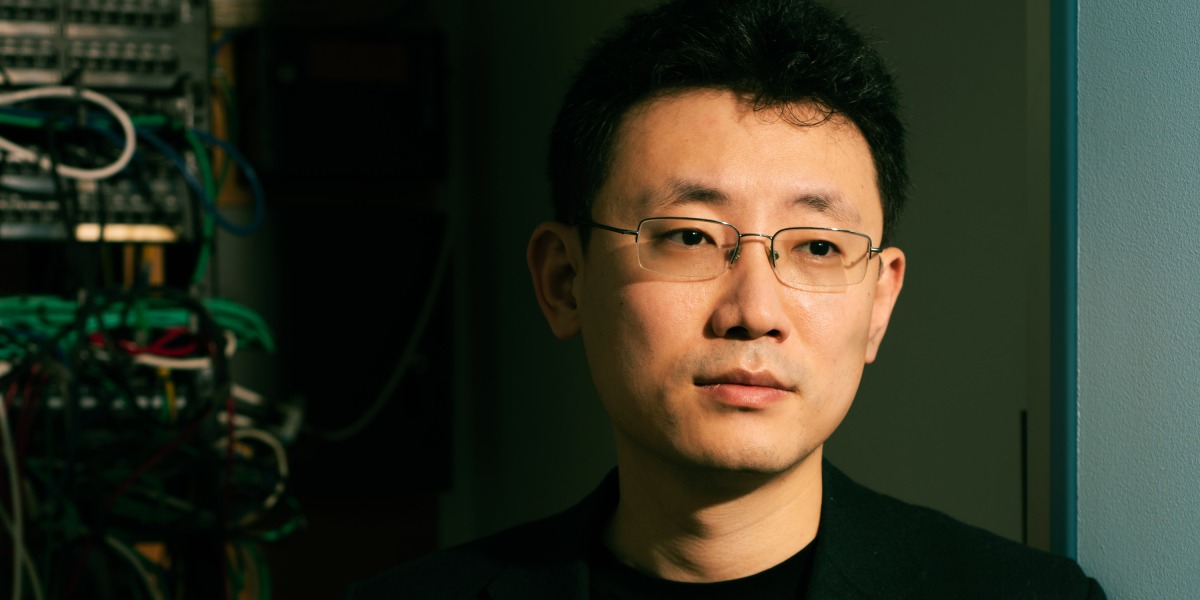

Johnson might wish he’d hired Ronghui Gu.

Gu is the cofounder of CertiK, the largest smart-contract auditor in the fizzy and unpredictable world of cryptocurrencies and Web3. An affable and talkative computer science professor at Columbia University, Gu leads a team of more than 250 that pores over crypto code to try to make sure it isn’t filled with bugs.

CertiK’s work won’t prevent you from losing your money when a cryptocurrency collapses. Nor will it stop a crypto exchange from using your funds inappropriately. But it could help prevent an overlooked software issue from doing irreparable damage. The company’s clients include some of crypto’s biggest players, like the Bored Ape Yacht Club and the Ronin Network, which runs a blockchain used in games. Clients sometimes come to Gu after they’ve lost hundreds of millions—hoping he can make sure it doesn’t happen again.

“This is a real wild world,” Gu says with a laugh.

Crypto code is much more unforgiving than traditional software. Silicon Valley engineers generally try to make their programs as bug-free as possible before they ship, but if a problem or bug is later found, the code can be updated.

That’s not possible with many crypto projects. They run using smart contracts—computer code that governs the transactions. (Say you want to pay an artist 1 ETH for an NFT; a smart contract can be coded to automatically send you the NFT token once the money arrives in the artist’s wallet.) The thing is, once smart-contract code is live on a blockchain, you can’t update it. If you discover a bug, it’s too late: the whole point of blockchains is that you can’t alter stuff that’s been written to them. Worse, code that’s hosted on a blockchain is publicly visible—so black-hat hackers can study it at their leisure and look for mistakes to exploit.

The sheer number of hacks is dizzying, and they are wildly lucrative. Early last year, the Wormhole network had more than $320 million worth of crypto stolen. Then the Ronin Network lost upwards of $600 million in crypto.