This is just one incident, but as the idea of building social creditworthiness increasingly seeps into other regulations, it reveals the risks of standardizing a practice wherein the government makes moral judgments for its people.

Just last week, China’s Cyberspace Administration finalized a regulation entirely dedicated to “online comments,” which I covered when it was first proposed in June. The regulation’s main purpose is to place social media interactions, including those in newer forms like livestreams, under the same strict controls China has always had for other online content.

These rules aren’t really part of the broader social credit system, but I still found some familiar language in the document. It asks social media platforms to “carry out credit assessments of users’ conduct in commenting on posts” and “conduct credit appraisals of public account producer-operators’ management of post comments.”

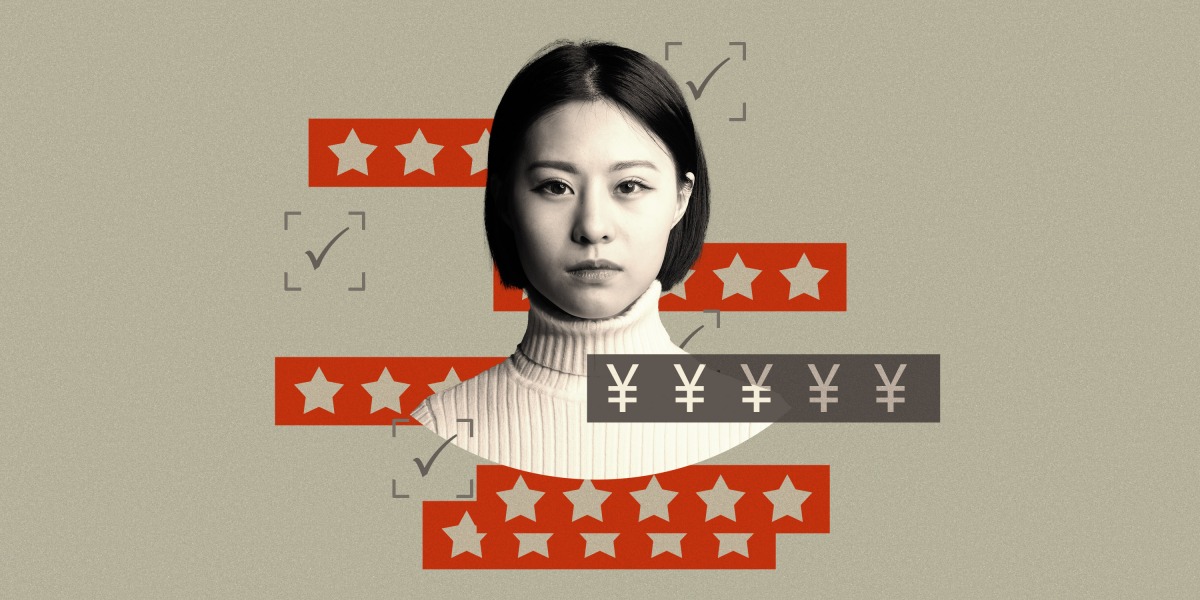

The idea is that if an influencer or a user posts things that are not trustworthy, that should be reflected in the person’s credit assessment. And the results of the credit assessment will determine “the scope of services and functionality” people are offered on certain platforms.

It’s not the only specific example of the Chinese government using importance of “creditworthiness” or “trust” to justify more rules. This was seen when the government decided to establish a blacklist of celebrities who promote “bad” morals, crack down on social media bots and spam, and designate responsibilities to administrators of private group chats.

This is all to say that the ongoing development of China’s social credit system is often in sync with the development of more authoritarian policies. “As China turns its focus increasingly to people’s social and cultural lives, further regulating the content of entertainment, education, and speech, those rules will also become subject to credit enforcement,” legal scholar Jeremy Daum wrote in 2021.

Nevertheless, before you go, I do want to caution against the tendency to exaggerate perceived risks, which has happened repeatedly when people have discussed the social credit system.

The good news is that so far, the intersection of social credit and the control of online speech has been very limited. The 2019 draft regulation to build a social credit system for the internet sector has still not become law. And a lot of the talk about establishing credit appraisal systems for social media, like the one requested by the latest regulation on online comments, looks more like wishful thinking than practical guidance at this point. Some social platforms do operate their own “credit scores”—Weibo has one for every user, and Douyin has one for shopping influencers—but these are more side features that few in China would say are top of mind.