At first glance, it might look like the pandemic-era supply chain chaos is nearly over.

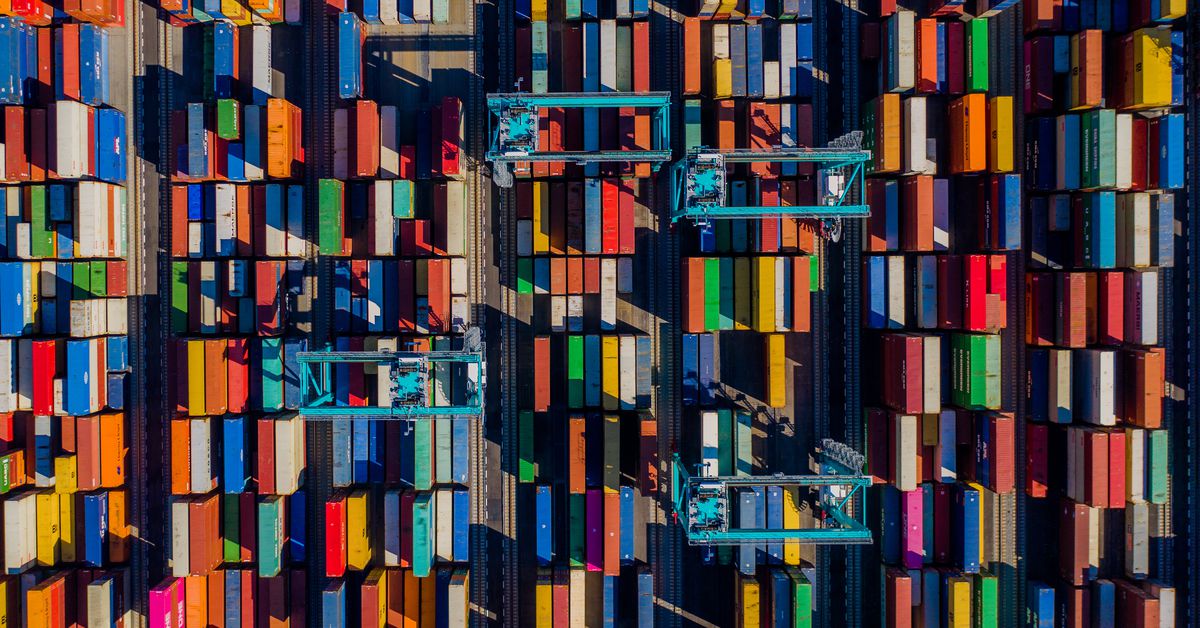

Headlines bemoaning shortages of everything from PlayStations and Care Bears to medical devices are no longer a daily occurrence. Just six vessels were waiting to dock at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach on Tuesday — a tiny fraction of the 109 that were stuck outside the San Pedro Bay back in January. Meanwhile, the cost of sending a 40-foot shipping container from Asia to the West Coast is now under $3,000, far below last year’s high of more than $20,000.

Still, the structural problems that enabled many of the delays, price hikes, and shortages over the past few years haven’t gone away. Shipping prices have not quite returned to their pre-pandemic levels, truck drivers are still in short supply, and some in the logistics industry are already predicting that there will be problems during the upcoming holiday season. More broadly, the capitalist system responsible for manufacturing and delivering goods throughout the world has not been “fixed.” In fact, it remains as vulnerable to disruption as ever. Consumers are still seeing widespread inflation, not only for energy and food but also for products that often depend on Pacific shipping routes, including apparel and new vehicles, according to the consumer price index summary published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics last week.

“If the supply chain is a patient coming into the ER, then it’s not bleeding to death anymore,” said Daniel Maffei, the chair of the Federal Maritime Commission. “But there are still a lot of issues with the supply chain. Some of them and maybe even the bulk of them predate Covid.”

Other problems, including the energy crisis created amid Russia’s war in Ukraine, mean that even if shipping costs continue to fall, those price declines won’t necessarily be passed on to average people. And plenty of products are still hard to find. Covid-19 shutdowns in China, which manufactures much of the goods sent to the US, has delayed the production of products from clothing to contrast media, a special dye needed for medical imaging. Packaging problems at a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant seem to have contributed to a nationwide shortage of Adderall. Disruptions in the US’s supply of carbon dioxide have made it more difficult to produce certain types of beer, while low water levels have slowed shipping on the Mississippi River and raised the cost of delivering corn and soybeans.

These challenges highlight the complexities and sheer vastness of the supply side of global economics. Although some refer to this system broadly as the supply chain, it’s actually made up of many interconnected and interwoven supply chains. A single company can rely on hundreds of different supply chains that each depend on many different products, components, and companies, sometimes located throughout the world. Every supply chain has its own strengths and vulnerabilities, and resolving bottlenecks in just one isn’t enough to eradicate shortages or bring down overall prices for consumers.

Recode asked eight experts to evaluate the state of the supply chain. Some acknowledged ongoing efforts to make different industries more resilient, but they said many of these projects are years in the making or rely on machinery and products that are affected by the same manufacturing and shipping problems that are impacting consumer goods. Companies aren’t necessarily financially incentivized to change their long-term approach, either. Others defended the supply chain and said that, while there certainly were delays, the system never really “broke” at all.

“Supply chains just adjust, but they were hit with a global pandemic,” said Chris Caplice, the executive director of MIT’s Center for Transportation and Logistics. “You saw all the warts and everything, but it kept working.”

Still, the vulnerabilities we saw throughout the pandemic could become a problem. While Covid-19 was certainly an unprecedented global event, there’s no reason to think future disasters won’t impact international trade all over again. Potential geopolitical conflict, and the devastating impacts of climate change, are already on the horizon. These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Is the supply chain making inflation less bad, or making things worse?

Willy Shih, Harvard Business School management practice professor: Retailers have too much of the wrong inventory, which they’re trying to unload. Demand has dropped, so the shipping rates have dropped, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t still bottlenecks or increased costs, whether it is labor costs or primary materials cost.

Shipping historian Marc Levinson: For many years, the [Federal Reserve] could count on imports to help keep down goods price inflation. We had cheap stuff coming in great volume from China, and that made it very hard to raise prices in the US market. That’s no longer the case. Globalization is no longer restraining inflation in that way.

Elif Akçalı, University of Florida industrial and systems engineering professor: These new numbers are worrisome for their implications for the supply chains in the near future. High inflation rates will not only increase the expenses associated with handling and storing inventory in a supply chain, but will increase the cost of borrowing money to acquire inventory for the supply chain in the first place. Hence, the total costs associated with acquiring, handling, and storing inventory will go up.

Shipping prices are declining, but what’s the overall state of the supply chain?

Daniel Maffei, Federal Maritime Commission chair: The bulk of the problem does seem to be more inland. It’s like a sink, right? If the sink clogs up, you say the sink is broken, but it’s not really the thing that’s broken. You don’t throw away the sink. It’s the pipes!

Our supply chain issues are now deeper in the supply chain — farther inland — and involve things like equipment shortages and lack of ability to get the equipment around, more than they have to do with the ports. Now it’s leading to congestion at some of our ports. We need more [empty containers] in the middle of America, and we have too many sitting at our ports.

Sharae Moore, president of She Trucking, a diversity-focused trucking nonprofit: The supply chain is in a state of transition. We are experiencing the supply chain pivoting into the 21st century of technology! We have noticed more companies testing autonomous vehicles and incorporating automation within their supply chain systems. Within the next five years, automation will dominate the industry. We also see the need for improvement in the area of shipping and receiving products to ensure that they get to the consumer faster. There is an urgent need to educate and train new drivers to meet this high demand.

Fiona Lowbridge, client success vice president at ALOM Technologies: The infrastructure is still struggling — ports, roads, bridges, airports, and other physical elements. We are also hurting from the lack of technology collaboration, more disjointed regulations, and disruptions. I am also troubled by the impact of climate change on the supply chains — for instance, our inability to move freight on barges due to low water levels in the rivers.

Why isn’t the supply chain back to “normal,” compared to before the pandemic? What issues remain?

Chris Caplice, executive director of MIT’s Center for Transportation and Logistics: Did you really not get everything you wanted during the pandemic? I would argue that supply chains never stopped working, even in the heat of the shutdown and lockdown. It took a little longer sometimes. … So we complain about toilet paper being out, but were you really ever that short?

Akçalı: Shipping accounts for only one aspect of supply chain operations. If a supply chain is being operated the way it was being operated prior to the pandemic … then this just means that the system is brought back up “as is,” with the vulnerabilities it had before the pandemic. It is as if the pandemic did not happen. It is as if we learned nothing from our experiences during the pandemic.

Moore: Compared to when the pandemic started, carriers both large and small were battling increased fuel rates, decreased freight rates, high insurance premiums, a lack of truck parking, and an increase in equipment costs. Before the pandemic, we saw mega-carriers going out of business and a driver shortage. I would like to see increased opportunities for professional truck drivers and minorities to advance into higher management positions within the supply chain.

Nick Pinkston, founder and CEO of Volition, an industrial components marketplace: People are trying to make factories to make things here, too. I’m thinking of one particular person right now who is making a sheet metal plant, and they are buying all these motors to make the machines. They’re five months behind. They’re having to either redesign their machine to accept different motors or they have to wait five months. It’s bad either way.

Shih: Some areas are getting better, and I think they’ll continue to get better rapidly. For example, the auto sector, where supplies and parts have been short — chips, in particular — is improving rapidly. There are some sectors where it’s still going to take a while.

Is the supply chain more resilient today than it was at the beginning of the pandemic?

Levinson: It’s hard to generalize about supply chain reliability. In general, yes, our supply chains are working much better than they were. But they’re not working smoothly in many cases.

Pinkston: If the pandemic were to happen today, I think we would actually be only a little bit better. This kicked off a bunch of initiatives that have yet to really play out. It’s going to take years to actually build this resiliency, and it’s always going to be a short-term profit to not do this stuff. … If you build this redundancy, and everyone holds more inventory, all the prices go up permanently. We can’t trust companies alone because they will always underinvest in this stuff.

Akçalı: Structural changes that are needed to truly build resiliency into supply chains — such as diversified supplier pools, increased emergency stockpiles for critical goods, increased visibility into supplier operations, thoughtful sharing of demand and supply risk throughout the entire supply chain, etc. — will not only take time but also require addressing the way business is done, and shifting the focus from cost minimization to the time needed for recovery.

Lowbridge: It has become increasingly clear that some raw materials are only produced in certain countries or regions. I think we should all worry about the impact of this concentration. It makes all of us vulnerable. I continue to be concerned about the physical infrastructure, as it will take a long time to fix it. We need to be able to scale our infrastructure where, right now, the infrastructure is crumbling.

Any advice for consumers?

Caplice: You’re gonna find discounts everywhere. Go to TJ Maxx, go to Marshalls. Target is taking millions of dollars right off inventory because stuff is coming in they couldn’t cancel fast enough. I think Black Friday this year is going to be a non-event. It’s probably already started early because retailers are getting nervous because demand is dropping. The same thing is going to happen with pickup trucks and cars that were mothballed because they didn’t have chips. Chips are going to come, and then there’s going to be a glut.

Go hug a driver or hug a worker in a distribution center. People who work on the front line are severely underappreciated, and they never stopped working.