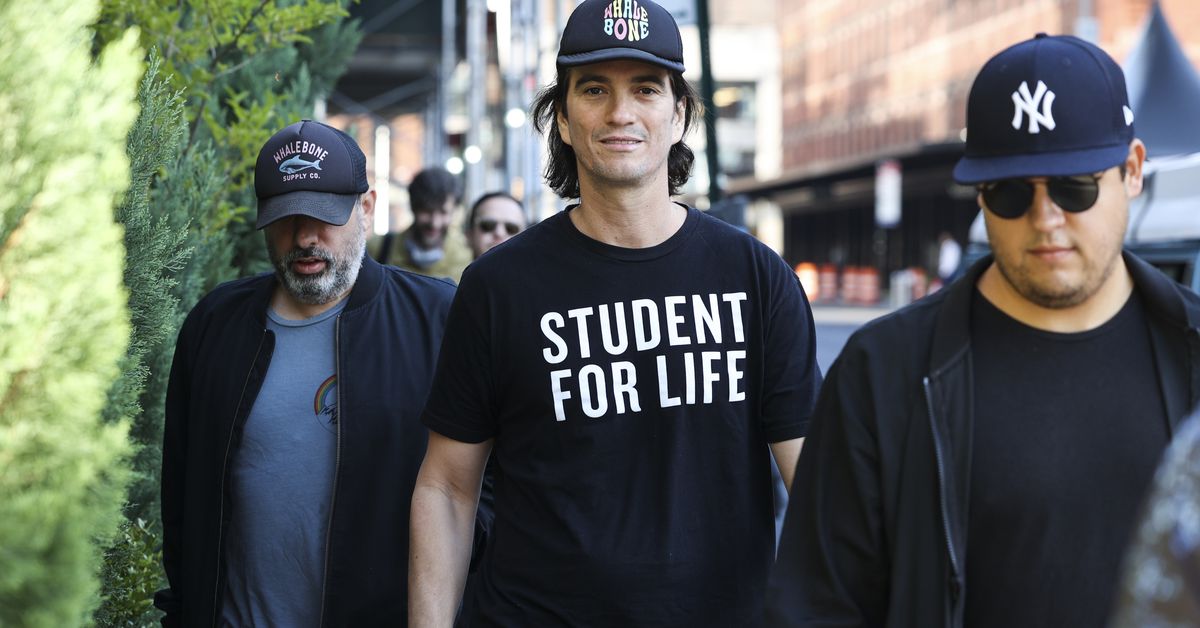

Housing in the United States has a problem. And Adam Neumann, the charismatic founder known for successfully rebranding shared office space as WeWork, and unsuccessfully running it, thinks he has a solution: Flow. This residential real estate startup wants to address a wide variety of issues, including housing availability, a lack of social interactions in a remote world, and the inability of renters to gain equity.

The housing shortage is certainly a big deal. The US was short nearly 4 million housing units as of late 2020, and the problem is spreading across the country. The inability to buy a home has huge repercussions on everything from Americans’ quality of life to their ability to create wealth. The problem is big enough that venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) is writing its biggest check to date — $350 million, valuing the company at $1 billion — to invest in Flow with the hope that the company can disrupt residential real estate through technology.

What any of that means is not exactly clear. What we do know is that Flow plans to operate more than 3,000 apartments that Neumann recently acquired, and that the company will likely add community features and provide the opportunity for renters to gain equity.

The big open question here is whether this failed founder and the veneer of technology will actually do anything to help the housing crisis in the US. It’s notable that one of the main problems with US housing is there’s not enough of it. While the issue there stems from exclusionary zoning, private equity’s mad dash to buy rental homes — like the thousands of apartments Neumann and friends gobbled up — is not making things better.

While offering people the ability to gain some sort of equity stake in their apartments could help people build wealth, Flow’s rentals are probably for those who are already relatively rich. The Nashville property Neumann bought, for instance, features a saltwater pool, valet trash pickup, and a dog park. Add on top of that all the premium services and community-building aspects Neumann’s properties will supposedly offer, and things get even pricier.

It also looks like the project will involve the blockchain. There are a few clues that suggest this, including several trademark applications uncovered by the Wall Street Journal. The filings for an entity related to Flow mention real estate development, co-living space management, and cryptocurrency trading services. We also know that both Neumann and Andreessen recently teamed up on a similarly named project, Flowcarbon, which aims to apply blockchain technology to the market for carbon credits. Additionally, it’s likely Flow will have to use some sort of nascent tech to justify its billion-dollar valuation before the startup has done a thing.

When WeWork filed to go public, many pointed out that the real estate company was going out of its way to convince people it was a tech company — and, by extension, to justify its sky-high valuation. This time around, you can almost see the wheels turning in Neumann’s head. What’s more cutting edge than Web3? The rebranding of crypto and blockchain could purportedly change the internet as we know it, wresting control of the web away from big tech companies, like Facebook and Google, and giving it back to creators.

Sure, that sounds great. But what does that have to do with real estate, community, and giving renters equity?

Arpit Gupta, a real estate expert and professor of finance at NYU’s business school, surmises that Flow might try to combine a number of existing things and market them into one. Those include timeshares (flexibility!), co-ops (equity!), layaway financing (access and equity!), and luxury buildings in trendy areas (well-heeled millennials). Perhaps, Flow wants to offer short-term apartments with company-provided financing where you could grow your ownership stake the longer you live there.

“It’s like WeLive 2.0 combined with some sort of rent-to-equity system,” Gupta imagined. Oh, and they will probably launch a token — for finance and fun — that would allow more people an ownership stake in the business and create a lot of buzz.

Flow would by no means be the only company trying to bring technology to bear on real estate. Venture capital-funded tech startups are tackling everything from real estate investing to helping finance renters into becoming owners. Web3 real estate companies, specifically, tend to involve putting property rights on the blockchain and tokenizing equity shares in buildings, according to Gupta.

We also don’t yet know the full scope of Neumann’s latest plans. In addition to Flow and Flowcarbon, a search of related trademark applications turns up Flow Life (investment and crypto trading services), Workflow (workspace design), Flow Village (online professional networking) and Kibbutz (educational services and social networking platform). Of course, just because you file for a trademark doesn’t mean you’re actually going to do something.

But as we know from the fate of WeWork’s one-time umbrella organization, the We Company, Neumann’s ambitions don’t exactly hew to what’s possible. In addition to running an ever-growing portfolio of coworking spaces, the We Company also branched out into seemingly unrelated businesses, including a school and an engineering firm that makes wave pools. Neumann is also well known for being a profligate spender and a poor manager of money — behaviors that ended up contributing to the downfall of his company.

Nevertheless, Neumann’s reputation and wild ambitions still haven’t curbed his ability to raise money.

“In Silicon Valley, there is always money for the repeat founder,” Eliot Brown, Wall Street Journal reporter and author of WeWork tell-all The Cult of We, told Recode. “Failure doesn’t seem to stop people.”

That’s particularly the case here. Andreessen is partially responsible for the cult of the founder, a term that refers to the mythical status given to founders who are thought to do no wrong. Now, his VC firm is funding Neumann’s return to glory.

“One of the ironies is that the big fuel behind the rise and fall of WeWork was this fetishization of the founder,” Brown said. “Adam became sort of the paragon of the founder gone wild and that was a creation, in large part, of the mystique that Andreessen put out about founders.”

For Andreessen, however, Neumann’s experiences and failures are a virtue.

“We understand how difficult it is to build something like this and we love seeing repeat-founders build on past successes by growing from lessons learned,” Andreessen wrote in his recent blog post. “For Adam, the successes and lessons are plenty.”

Presumably that means Flow will have no wave pool.

This story was first published in the Recode newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one!