This story is part of a Recode series about Big Tech and antitrust. Over the next few weeks, we’ll cover what’s happening with Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, and Google.

If Microsoft is worried that the anti-Big Tech, pro-antitrust movement will finally come for it, you wouldn’t know it. The company announced on January 18 that it would make the largest acquisition in its history, buying up Activision Blizzard, one of the biggest video game publishers in the world. If the $69 billion deal goes through, Microsoft will become the third-largest gaming company in the world by revenue. Its library of games will expand significantly, potentially giving its Xbox console and Game Pass subscription program an edge over Sony’s PlayStation and rumored Game Pass rival.

Opinions are mixed about how good for the gaming industry the merger will be. You may not be a gamer, but a lot of other people are. It’s a huge business, raking in about $180 billion globally last year. Microsoft says about 3 billion people play video games now, and it expects 4.5 billion will play by 2030.

Some are concerned that Microsoft will use the purchase to monopolize an increasingly consolidated gaming market and exclude rivals; others see it as a way to level an expanding playing field and even promote more competition, not squelch it. Microsoft says it wants to offer as many games as possible to as many people as possible on as many devices as possible — including in new spaces like the metaverse, the virtual world that some companies (most notably, Facebook) see as the next tech frontier. There’s nothing more metaverse-y than games, where people already create virtual versions of themselves and navigate virtual worlds, often interacting with virtual versions of other, real, people along the way.

The timing of Microsoft’s announcement wasn’t ideal. In an unfortunate coincidence, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), which enforce antitrust laws in the United States, announced a few hours later that they are working together on new guidelines for mergers that take the digital economy into account. The FTC and DOJ’s antitrust divisions are headed by prominent Big Tech critics — Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter, respectively — who have advocated for using antitrust laws to curb those companies’ size and influence. Microsoft’s massive merger almost seems to be daring them to do something about it.

Microsoft has had a relatively smooth ride through the scrutiny and criticism that has plagued its four Big Tech rivals — Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google — over the last few years, even though it’s worth more than most of them. This conspicuous merger threatens to upend that. Microsoft knows better than anyone what the consequences of going up against the government are: Twenty years ago, a protracted antitrust lawsuit from the DOJ almost broke up the company. Back then, Microsoft stood alone as the big, bad tech monopoly. Now it stands alone as the Big Tech company that lawmakers and antitrust enforcers don’t have much of a problem with.

“It’s odd how you can fall out of the field of vision, even though you’re an extraordinarily important company,” William Kovacic, who served as chair of the FTC under President George W. Bush, told Recode.

The Activision acquisition will make it that much harder for lawmakers and regulators to ignore Microsoft. There’s no guarantee that the merger will be approved, and it’s all but certain that antitrust enforcers will look at it very closely. But Microsoft also knows better than its Big Tech rivals what to do to appease them, and has been working for years to improve its reputation and image after the beating both took more than 20 years ago. It must think its chances are good enough to take the risk.

Microsoft may well get Activision. Or it may find itself back in the antitrust hot seat it left years ago.

The poster child for Big Tech antitrust grows up

Microsoft was once synonymous with antitrust and Big Tech. Even now, it’s the example in the definition of a monopolization on the FTC’s website, which details how Microsoft used its monopoly on computer operating systems to exclude and harm competitors — especially the nascent web browser market.

Microsoft’s problems with antitrust enforcers began in the early ’90s, when it was investigated by both the FTC and the DOJ over how it used licensing agreements with computer manufacturers to cement the dominance of its Windows operating system. In 1994, Microsoft entered into a consent decree with the DOJ. Among other things, the company said it wouldn’t require computer manufacturers to buy other Microsoft products when they bought Windows licenses.

But the very next year, Microsoft began bundling its new Internet Explorer browser with Windows 95. Not only was Internet Explorer the default web browser on Windows 95 computers (and Macs), but Microsoft also made it nearly impossible to uninstall Internet Explorer and very difficult to install a competitor’s browser. Internet Explorer was far and away the most used browser for years — about 95 percent of the market at its peak — even though it was arguably worse than some others.

The DOJ sued in 1998, accusing Microsoft of violating its consent decree not to force other Microsoft programs on Windows machines. Microsoft said Internet Explorer wasn’t a separate product but an integral part of Windows. The DOJ won, and the penalty to Microsoft was severe.

A judge ordered Microsoft to break up into two different companies: one for the operating system, and one for everything else. That ruling was overturned on appeal. In 2002, the DOJ and Microsoft settled. The terms were better than being broken up, but Microsoft didn’t get off scot-free. The company had to make it easier for third-party software to work with Windows, couldn’t punish manufacturers for including third-party software on its machines, and had to submit to years of government oversight. There were also billions in fines and settlements to end other antitrust cases brought by other companies, states, and countries.

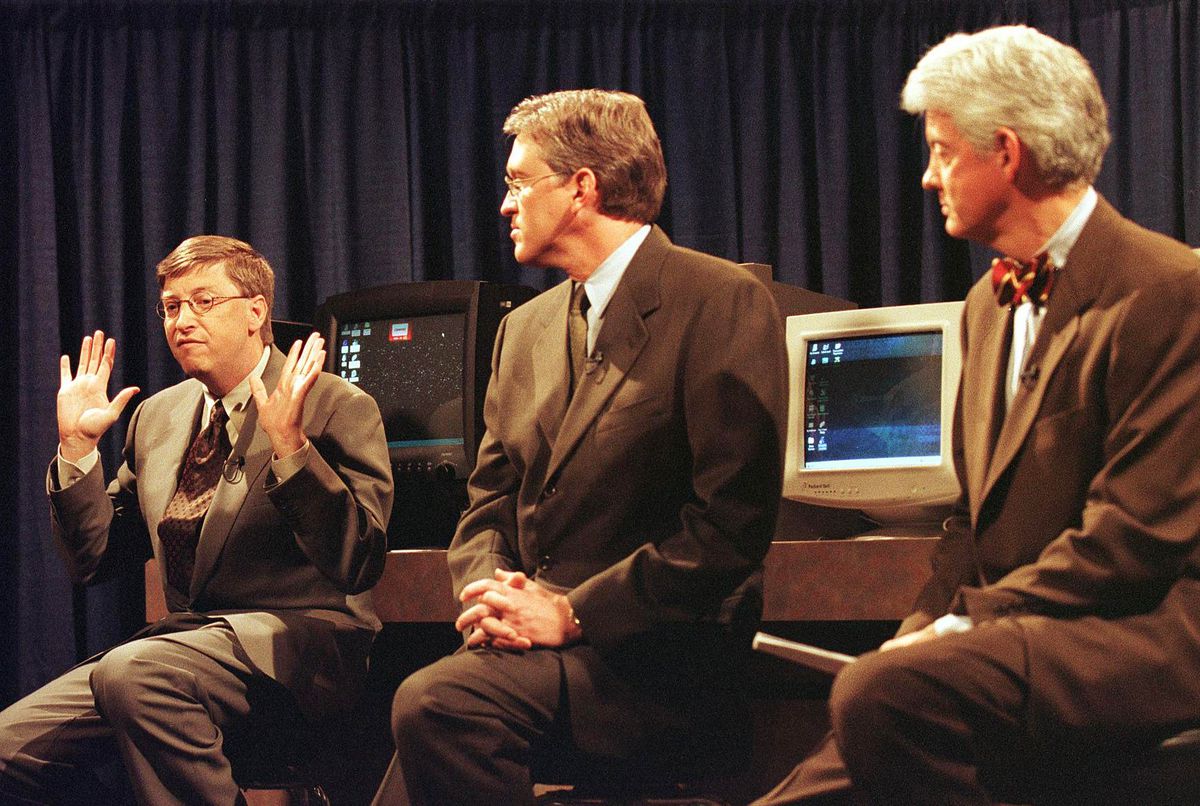

“They learned in a big way, at a time that antitrust really had not put anyone under the microscope like Microsoft was,” Michael Carrier, professor at Rutgers Law School, told Recode. “This was front-page news, every day was what happened in the trial that day. [Then-CEO Bill] Gates did not come across well. It really was a wake-up call.”

The impact on the tech industry was sizable and is still felt today. During the years that the case wound its way through the legal system — and for the ensuing years when Microsoft had to follow a consent decree, which only ended in 2011 — the company didn’t want to do anything that would incur the further wrath of antitrust enforcers. If Microsoft still controlled 95 percent of our access to the internet, it could very well be forcing us all to use Bing and Outlook instead of Google and Gmail, or blocking users from going to Facebook in favor of its own, very similar, social networking site. Other tech companies were able to gain a foothold when Microsoft was scared to move.

“Microsoft has now had more than 20 years to hone its message to try to distinguish itself from the other big tech companies and say we’re different, we’re here to help you, we’re focused on the industry and the economy at large,” Carrier said. “They have been owning that message for years.”

Microsoft president Brad Smith and CEO Satya Nadella have worked for the company for decades, including during its antitrust woes. Now they write books about how technology companies have a responsibility to make sure their innovations aren’t harming society and to make that society better. (Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, by comparison, has been blamed for contributing to everything from eating disorders to genocide.) Microsoft is careful about what it does and how its actions could be perceived. It works hard to build and maintain good relationships with the people and agencies it doesn’t want to get on the wrong side of because it knows better than anyone else how important that is.

“I think the company as a whole learned a lot from our experience in the 1990s,” Rima Alaily, Microsoft’s deputy general counsel for the competition law group, told Recode. “It had a lasting impact on our culture and how we view our role in society and what responsibility we have to take with respect to our technology, and how we have to engage with government, partners, and customers.”

How Microsoft “tried to get ahead” of regulators

While antitrust advocates lambast Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google for being too big, Microsoft has a market cap of about $2.3 trillion, making it the second-most-valuable company in the world (only Apple is bigger). It’s a tech conglomerate with many lines of business, from software to social media. Generally, Microsoft is more enterprise-focused than the others, which makes it easier for the general public to overlook. The company either doesn’t do the things that the other Big Tech companies have been criticized for, or it isn’t seen as a dominant, potentially abusive, presence in those spaces with too much power over large swaths of the economy.

Microsoft has also been careful to keep tabs on public sentiment and avoid (or stop) doing things that get the kind of negative attention that lead to, say, sweeping congressional investigations, bills targeted at curbing specific business practices, and crackdowns from government agencies.

“In many areas, like in how we run our app stores, we’ve tried to get ahead of where regulators and legislators are signaling they’re going, rather than fight needed change,” Alaily said.

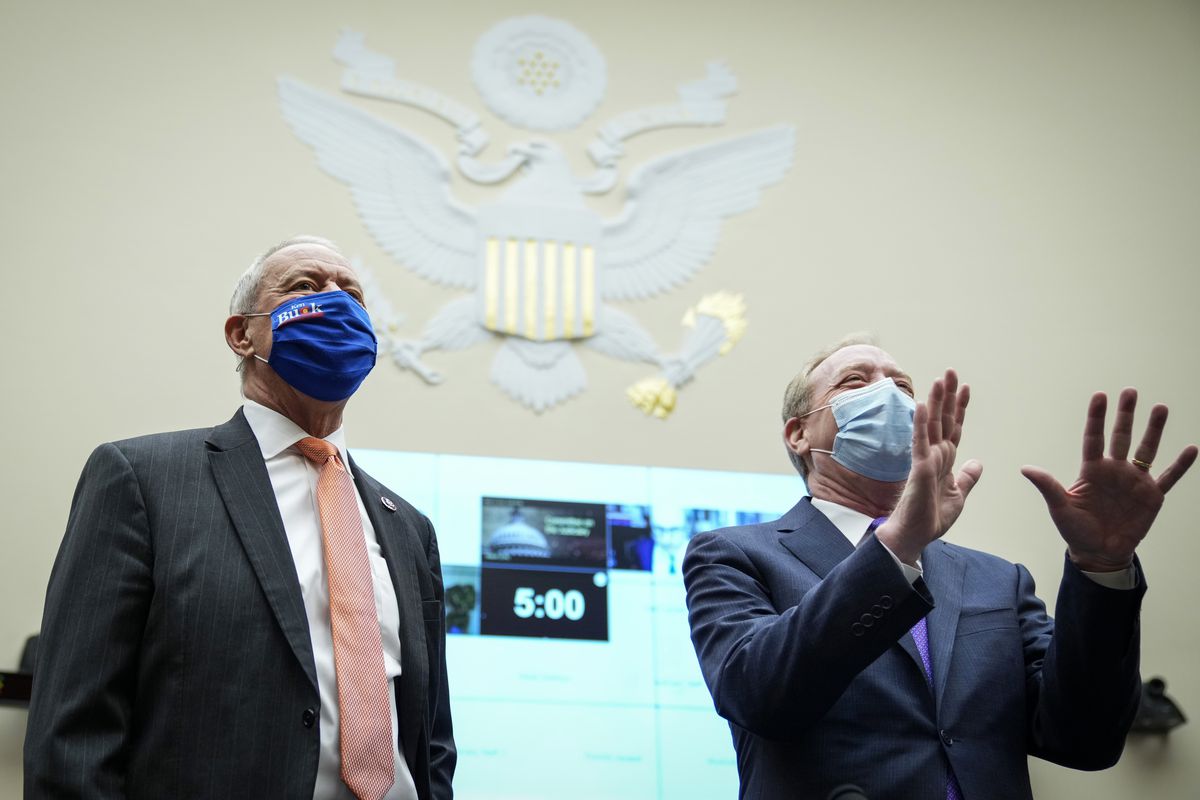

With a few exceptions, lawmakers have skipped over Microsoft in their crusade to curb Big Tech’s power, even using Microsoft as a resource when investigating those companies. Microsoft was not only left out of the House Judiciary Committee Democrats’ report on competition in digital markets, but Smith was also invited to brief the House for it. Smith also testified against Google’s dominance before the House antitrust subcommittee last year. While Microsoft says some of the bills in Congress’s big antitrust package could apply to it as well, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google are very clearly the main targets of it.

Microsoft also has a long-established presence in DC, which it realized the need for when it got hammered decades ago. Its lobbyists have been working for years to build solid relationships with politicians. Smith is seen as an eager ambassador for Microsoft, while other companies had to go on apology tours that arguably came too late. When President Trump needed a company to buy off part of TikTok, he talked to Microsoft — in between tweets lashing out at other Big Tech companies.

“If you were to go back 10, 15 years ago, a lot of other tech companies just had this disdain for Washington and for lobbying in general,” said Nu Wexler, a DC-based communications consultant who worked in policy communications at Twitter, Google, and Facebook. “The other companies didn’t want to invest in their Washington offices. Microsoft … saw the need.”

Microsoft also knows how to play the antitrust compliance game. That yearslong consent decree forced its hand, sure. But even after that expired in 2011, Microsoft has been careful to look as though it’s toeing the line, rather than see if it can get away with crossing it.

Many now see Microsoft as having done its time, learned its lesson, and been punished enough. Even lawmakers who are usually eager to criticize Big Tech seemed almost positive about Microsoft’s Activision acquisition. Rep. Ken Buck, who has led the antitrust movement for Republicans in the House, tweeted that he was “encouraged” by Microsoft’s “assurances” to him that the merger would increase competition.

Microsoft’s antitrust outlook

Of all the acquisitions Microsoft could have chosen to make, the gaming industry — one of Microsoft’s more visible, consumer-facing segments — is the one that could elicit the most passionate responses from a sizable crowd. Including, very possibly, an FTC and DOJ looking for a merger to make an example of.

Microsoft points out that the acquisition would only make it third in the gaming market, which weakens the argument that it would suddenly own the space. But it also has its own gaming platform, the Xbox, and Windows PCs are the hardware of choice for big segments of gamers, too. Because the Activision acquisition would add some of the biggest games in the world (Candy Crush, Call of Duty, Overwatch, and World of Warcraft) to Microsoft’s game library (which already includes Minecraft, Halo, Gears of War, Age of Empires, and Fallout), there are concerns the company will make them all Xbox and/or PC exclusives. Or Microsoft could throw them all on its monthly Game Pass subscription service, which is available for most platforms but not PlayStation.

Daniel Hanley, senior legal analyst at Open Markets Institute, an anti-monopoly advocacy group, told Recode that the merger shouldn’t just be looked at in terms of where it will put Microsoft in the gaming market now, but the potential it has to disadvantage its competitors.

“It’s about what can Microsoft do with its portfolio of products and services, with this company, against its rivals and for the market?” Hanley said. “And what will happen to the market after Microsoft does this?”

Video game industry analyst Michael Pachter doesn’t think Activision will make Microsoft’s gaming arm too big to get enforcers’ approval, pointing out that even with Activision, Microsoft’s cut of the global video game market will only be 10 to 15 percent.

“Zero point zero percent chance that regulators in the US or the EU Competition Commission conclude that this makes them too big with pricing power,” Pachter said.

Pachter added that, to assuage concerns that Microsoft could act anti-competitively, the company can (and likely will) work something out with enforcement agencies. He sees Microsoft agreeing to conditions like not raising Game Pass prices for a set number of years and not pulling existing titles from PlayStation.

Microsoft says it intends to keep existing titles on other platforms, citing Call of Duty and PlayStation as an example. And it wants to move to a “player-centric” model, rather than a “device-centric” one.

“Gamers should be able to play whichever games they want, wherever they want, on whatever device they want,” Alaily said.

That might be a good business plan for Microsoft, as Xbox consoles are infrequent purchases from which the company doesn’t make a profit, while Game Pass is a consistent, monthly payment from 25 million people — a number that the acquisition will likely only add to. Detaching this from the Xbox gaming platform also lets Microsoft claim a much larger gaming market; it’s not just competing with Sony’s and Nintendo’s consoles, but also Apple’s mobile devices, Google’s cloud gaming service, Amazon’s gaming studio, and whatever Facebook is doing with the metaverse. It’s challenging the same Big Tech companies that regulators and lawmakers have been criticizing for years.

Microsoft will likely have to contend with scrutiny from the European Union, which is already looking into an antitrust complaint against Microsoft from cloud software company Nextcloud. The EU’s competition laws are stricter than those in the US, so maybe the people Microsoft really has to appease are across the Atlantic Ocean.

Microsoft expects to close the Activision deal sometime in fiscal year 2023, which starts this July. In US antitrust law, it’s illegal to monopolize; that is, to abuse a monopoly in ways that hurt competition and consumers. But it’s legal to be a big company, and it’s also legal to be a monopoly. Perhaps Microsoft is the best example of that now, after being an example of an illegal monopoly for so long.

“We’re hoping to accelerate this transition to subscription and cloud streaming that puts the player at the center of the experience,” Alaily said. “We feel really good about the deal.”

We’ll see if enforcers feel the same way.