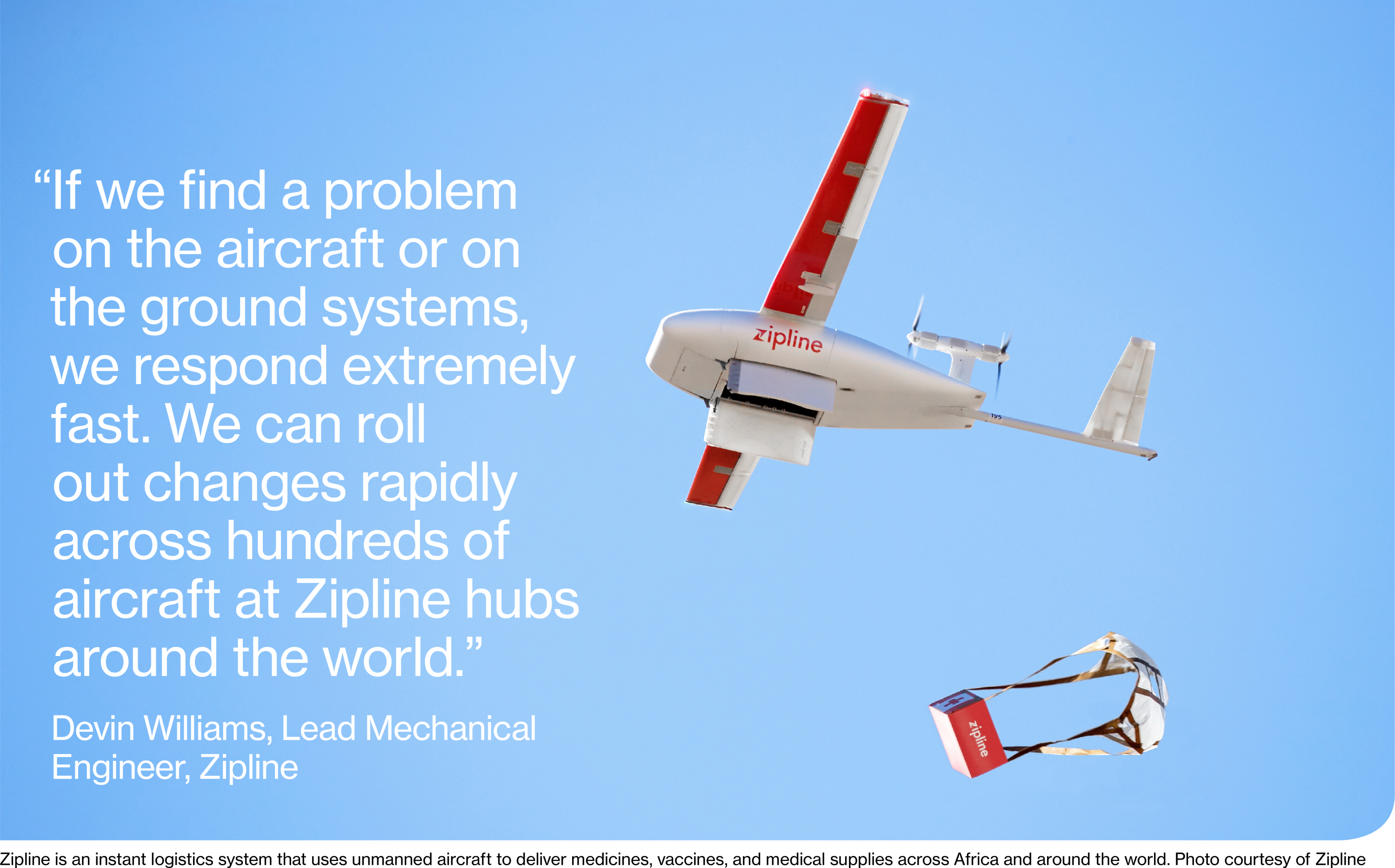

The company concentrated on solving the most challenging problems in the early design phase with sprints as a team and then moved into smaller groups for detailed design efforts. They used fast feedback loops in simulation and testing to improve the design before going into production.

This focus on agile development and manufacturing helped Zipline take its unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) from design to commercialized and scaled operations across Ghana and Rwanda in less than 18 months, a timeline that included six months of hardcore development, another six months of prototype testing, and a final six months in design validation and engineering verification.

“In general, the idea of focusing resources on a specific problem in sprints is something that we are taking from the software world back into the hardware world,” says Devin Williams, lead mechanical engineer on the UAV production platform at Zipline. “One thing we do really well is find the minimum viable product and then go prove it out in the field.”

Using an agile process allows Zipline to focus on releasing changes to the product that address customer needs quickly while maintaining high reliability. The San Francisco Bay Area company now has distribution centers in North Carolina and Arkansas, with another underway in Salt Lake City, and will soon be launching in Japan as well as in new markets across Africa.

Zipline is not alone. From startups to manufacturers with decades of history, companies are turning to agile design, development, and manufacturing to create innovative products at lower costs. Airplane manufacturer Bye Aerospace cut costs by more than half in its development of an electric airplane and sped up the cadence of its prototypes. And Boeing used agile processes to win the T-X twin-pilot trainer jet project with the US Air Force.

Overall, applying agile methodologies should be a priority for every manufacturer. For aerospace and defense companies, whose complex projects have typically followed the long time horizons of waterfall development, agile design and development are needed to propel the industry into the age of urban air mobility and the future of space exploration.

The evolution of traditional product design

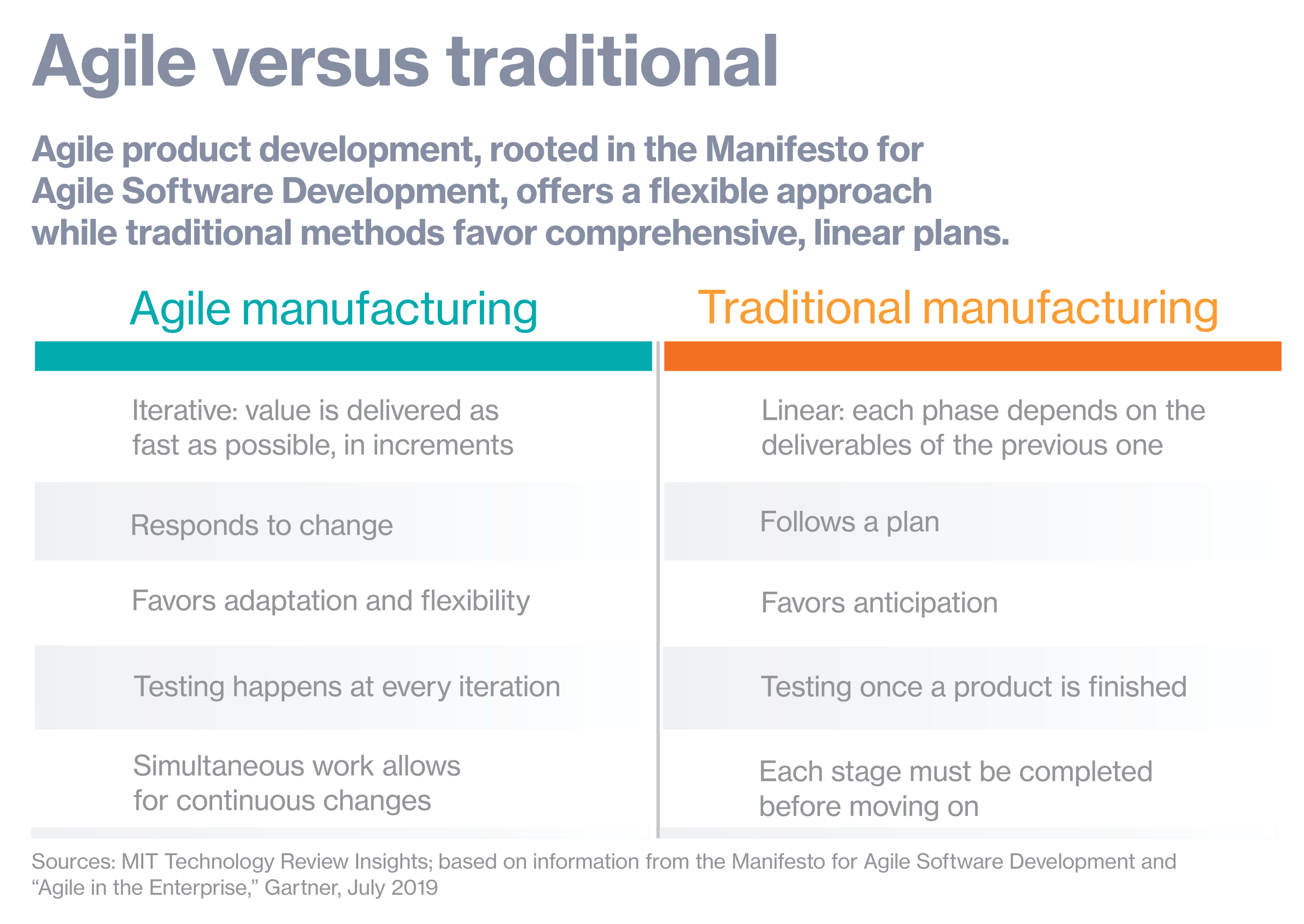

While agile production has its origins in the Kanban method of just-in-time auto manufacturing developed in the 1940s at Toyota, the modern agile framework for development was refined in the late 1990s by programmers looking for better ways to produce software. Rather than create a “waterfall” development pipeline that included specific stages, such as design and testing, agile development focused on creating a working product, the minimum viable product, as early in the process as possible and then iterating on the technology. In 2000, a group of 17 developers drafted the Agile Manifesto, focused on working software, individuals and interactions, and customer collaboration.

Over the past decade, agile software development has focused on DevOps—”development and operations”— which creates the interdisciplinary teams and culture for application development. Likewise, design companies and product manufacturers have taken the lessons of agile and reintegrated them into the manufacturing life cycle. As a result, manufacturing now consists of small teams iterating on products, feeding real-world lessons back into the supply chain, and using software tools to speed collaboration.

In the aerospace and defense industry, well known for the complexity of its products and systems, agile is delivering benefits. In working on the development of the T-X two-seat jet trainer, Boeing committed to developing agile design and manufacturing processes, which has resulted in half the program cost for the US Air Force, a 75% increase in the quality of the initial prototype, half the software development time, and an 80% reduction in assembly time.

“We adopted an agile mindset and a block plan approach to hardware and software integration,” says Paul Niewald, Boeing’s T-X program manager. “This had us releasing software every eight weeks and testing it at the system level to validate our requirements. By doing this, in such a disciplined way—at frequency—it allowed us to reduce our software effort by 50%.”

In the end, the T-X went from design to the building of “production-representation jets” in three years. This is a major departure from the initial development of traditional aircraft programs, which use waterfall development in the initial design and development stages and can require a decade of development.

Download the full report.

This content was produced by Insights, the custom content arm of MIT Technology Review. It was not written by MIT Technology Review’s editorial staff.