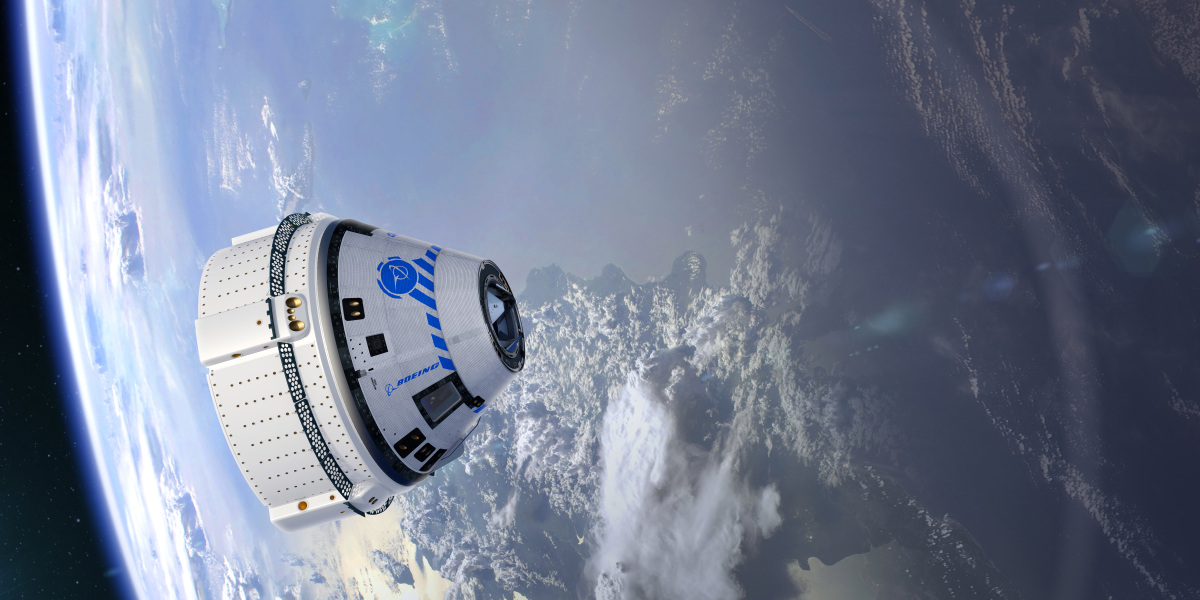

Now, Boeing is going for a high-stakes redo of that mission. On August 3, Orbital Flight Test 2, or OFT-2, will send Starliner to the ISS again. The company cannot afford another failure.

“There is a lot of credibility at stake here,” says Greg Autry, a space policy expert at Arizona State University. “Nothing is more visible than space systems that fly humans.”

The afternoon of July 30 was a stark reminder of that visibility. After Russia’s new 23-ton multipurpose Nauka module docked with the ISS, it began firing its thrusters unexpectedly and without command, shifting the ISS out of its proper and normal position in orbit. NASA and Russia fixed the problem and had things stabilized in under an hour, but we still don’t know what happened, and it’s unnerving to think what could have happened if conditions had been worse. The whole incident is still under investigation and has forced NASA to postpone the Starliner launch from July 31 to August 3.

It’s precisely this kind of near-disaster Boeing wants to avoid, for OFT-2 and any future mission with people onboard.

How Starliner got here

The shutdown of the space shuttle program in 2011 gave NASA a chance to rethink its approach. Instead of building a new spacecraft designed for travel to low Earth orbit, the agency elected to open up opportunities to the private sector as part of a new Commercial Crew Program. It awarded contracts to Boeing and SpaceX to build their own crewed vehicles: Starliner and Crew Dragon, respectively. NASA would buy flights on these vehicles and focus its own efforts on building new technologies for missions to the moon, Mars, and elsewhere.

Both companies hit development delays, and for nine years NASA’s only way of getting to space was by handing over millions of dollars to Russia for seats on Soyuz missions. SpaceX finally sent astronauts to space in May 2020 (followed by two more crewed missions since), but Boeing is still lagging behind. Its December 2019 flight was supposed to prove that all its systems worked, and that it was capable of docking with the ISS and returning to Earth safely. But a glitch with its internal clock caused it to execute a critical burn prematurely, making it impossible to dock with the ISS.

A subsequent investigation revealed that a second glitch would have caused Starliner to fire its thrusters at the wrong time when making its descent back to Earth, which could have destroyed the spacecraft. That glitch was fixed mere hours before Starliner was set to come back home. Software issues aren’t unexpected in spacecraft development, but they’re things Boeing could have resolved ahead of time with better quality control or better oversight from NASA.

Boeing has had 21 months to fix these problems. NASA never demanded another Starliner flight test; Boeing elected to redo it and foot the $410 million bill on its own.

“I fully expect the test to go perfectly,” says Autry. “These problems involved software systems, and those should be easily resolvable.”

What’s at stake

If things go wrong, the repercussions will depend on what those things are. Should the spacecraft experience another set of software problems, there’ll likely be hell to pay, and it’s very hard to see how Boeing’s relationship with NASA could recover. A catastrophic failure for other reasons would also be bad, but space is volatile, and even tiny problems that are hard to anticipate and control for can lead to explosive outcomes. That may be more forgivable.

If the new test doesn’t succeed, NASA will still work with Boeing, but a re-flight “might be a couple years off,” says Roger Handberg, a space policy expert at the University of Central Florida. “NASA would likely go back to SpaceX for more flights, further disadvantaging Boeing.”

Boeing needs OFT-2 to go well for reasons beyond just fulfilling its contract with NASA. Neither SpaceX nor Boeing built its new vehicles to carry out ISS missions—they each had larger ambitions. “There is real demand [for access to space] from high-net-worth individuals, demonstrated since the early 2000s, when several flew on the Russian Soyuz,” says Autry. “There is also a very strong business in flying the sovereign astronaut corps of many countries that are not ready to build their own vehicles.”

SpaceX will prove to be very stiff competition. It has private missions—its own and through Axiom Space—already slated for the next few years. More are sure to come, especially since Axiom, Sierra Nevada, and other companies plan to build private space stations for paying visitors.

Boeing’s biggest problem is cost. NASA is paying the company $90 million per seat to fly astronauts to the ISS, versus $55 million per seat to SpaceX. “NASA can afford them because after the shuttle problems the agency did not want to become dependent upon a single flight system—if that breaks, everything stops,” says Handberg. But private citizens and other countries are likely to plump for the cheaper—and more experienced—option.

Boeing could definitely use some good PR these days. It is building the main booster for the $20-billion-and-counting Space Launch System, set to be the most powerful rocket in the world. But high costs and massive delays have turned it into a lightning rod for criticism. Meanwhile, alternatives like SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and Super Heavy, Blue Origin’s New Glenn, and ULA’s Vulcan Centaur have emerged or are set to debut in the next few years. In 2019, NASA’s inspector general looked at potential fraud in Boeing contracts worth up $661 million. And the company is one of the main characters at the center of a criminal probe involving a previous bid for a lunar lander contract.

If there was ever a time Boeing wanted to remind people what it’s capable of and what it can do for the US space program, it’s next week.

“Another failure would put Boeing so far behind SpaceX that they might have to consider major changes in their approach,” says Handberg. “For Boeing, this is the show.”