YouTube has more than 2 billion users. It generates $20 billion a year. But those numbers don’t begin to explain the size and impact of the world’s biggest video site.

So let’s try this: YouTube is so big that you almost don’t notice it. It’s just always there, always on. It seems fundamental to digital life, like texting or email. Maybe, like my kids, you actively go to YouTube for entertainment or education. Maybe you’re like a lot of other people and end up watching YouTube without even knowing you’re doing it: You’re just watching a video, which means you’re watching YouTube.

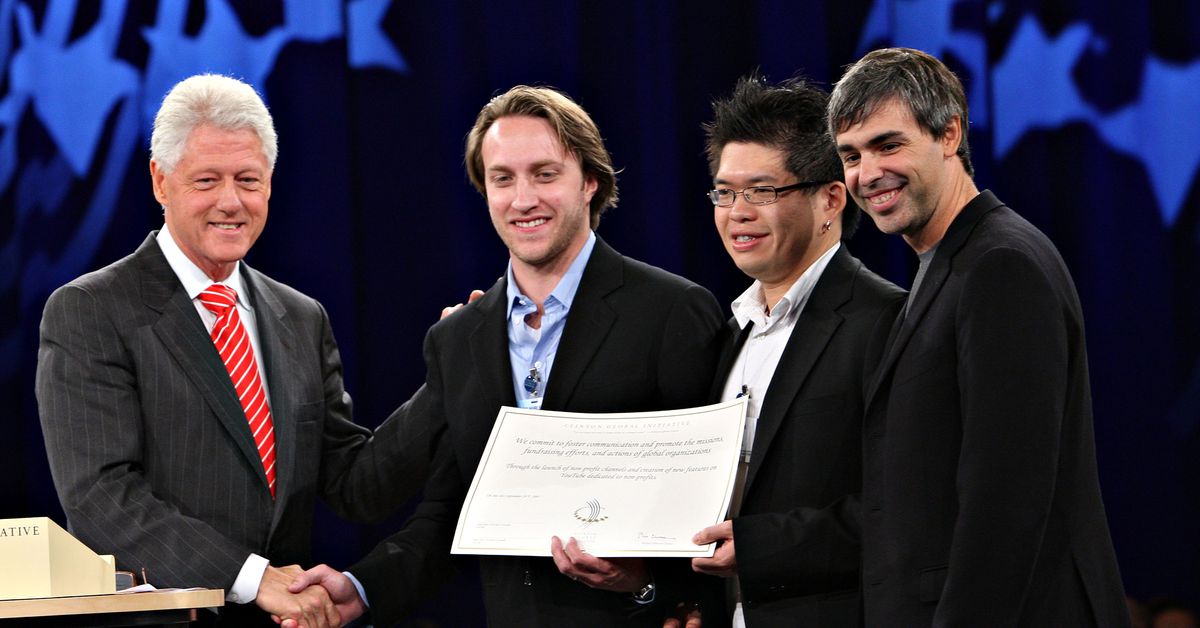

It’s also hard to get your head around how quickly YouTube got to this place: The site didn’t exist until 2005. And when Google bought it in 2006, it still seemed possible that the search giant had just wasted $1.65 billion. Sure, YouTube was a good place to watch dogs on skateboards or pirated “Lazy Sunday” clips, but what else could you do there?

Now we know: YouTube is a place where you can watch everything — great stuff, dumb stuff, useful stuff, dangerous stuff. And it’s a place where you can upload almost anything, if you’re inclined. Google is an open platform, meant to quickly distribute anything and everything, without any friction getting in the way.

Whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, or both, depends on your perspective.

As Shirin Ghaffary and I explore on this week’s episode of Land of The Giants: The Google Empire, YouTube — and Google — didn’t take a linear path to get to this place.

For instance: YouTube started out as a money-losing novelty built by a couple of guys from PayPal, and Google had its own plans to dominate internet video. But Google quickly pivoted and killed off its in-house site (there’s a reason you don’t remember something called Google Video) and snapped up YouTube instead.

Likewise: The first people who succeeded on YouTube didn’t really have a plan to “succeed on YouTube.” They were often just kids, like Smosh’s Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecox, who were doing it for fun and because using YouTube was easy.

But YouTube quickly figured out that it could give the Ian and Anthonys of the world a chance to make money from YouTube by giving them a cut of some of the site’s ad revenue. And now there’s a universe of people uploading videos and using YouTube for profit or power or both — and a constant push and pull within YouTube, which wants all of those videos on its site, except when it discovers that some of them have crossed the line.

What that line is — and how YouTube decides what that line is, and why it decides to ignore other stuff that seems line-crossing to many people — is a source of continual discussion in and outside of YouTube. It can be very difficult trying to figure out how and why YouTube polices its platform — up until June 2020, for instance, David Duke, the former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, had his own YouTube channel.

It also seems cleaning up the site will be a never-ending problem for YouTube and the world that YouTube affects. That’s because YouTube is an open platform, so it seems impossible to imagine a world where some combination of carefully written rules, thoughtful moderation, and robust machine learning keep the site free of odious users — the kind who might want to use the world’s biggest video site to spread misinformation about vaccines or election results or white supremacy.

But YouTube executives continue to insist that the benefits of running the site as an open platform are worth it — that YouTube, just like the internet, is full of everything, and we’re better off in a world where almost everything’s available with a click. It’s a complicated discussion, and an important one, which made it a great subject for a podcast: Listen here, and let us know what you think.

For more stories about Google’s incredible rise, covering everything from the mobile phone wars to the company’s internal tensions to its current antitrust battles, subscribe now to Land of the Giants: The Google Empire.