Apple’s privacy “nutrition labels” have been in the App Store for just over two months now. Privacy advocates were generally pleased to see these easy-to-read versions of app privacy policies; educating users about the secretive inner workings of their apps is almost always a positive development.

The labels are just one of Apple’s new policies to give users more privacy at the possible expense of the app economy, which largely relies on collecting and selling furtively acquired user data. In early spring, Apple will release iOS 14.5, which will force apps to get user permission to track users across different apps for ad targeting, a move that Facebook has vocally opposed — and its exceedingly long labels may be a good hint as to why. But that update only applies to tracking users across apps; the labels give users more information about the data being tracked as they use the app themselves. That could be useful information, if done right.

“Any additional transparency that companies and especially platforms like Apple can provide, in terms of how apps and companies are collecting and using personal data — that’s good,” John Davisson, senior counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), told Recode. “It’s good for consumers to be able to access that information.”

But in practice, some reviews have said, the labels need a little work. The Washington Post’s Geoffrey Fowler found some apps were not being truthful about their privacy policies in their labels, and that could create a false sense of security for consumers. The New York Times’s Brian X. Chen thought the labels were informative, up to a point. The labels gave him a sense of how much data an app was collecting about him, but not what that data was being used for.

Of course, those reviews have come from the perspective of tech journalists, who know more about data privacy and data collection than the average person. I wanted to know what normal people, who don’t spend their day thinking about Facebook Pixels and the fallacy of de-identified data, thought of the labels. Did they understand them? Did they learn anything from them? Did they change their behavior in any way? Did they even know the labels existed at all?

So that’s what I asked 12 (relatively normal) people: friends, family, and Vox readers. Here’s what I found — and where there’s room for improvement.

The labels only work if people know they’re there

Many of the people I spoke with didn’t even know the privacy labels existed, which is a problem for a feature that’s meant to provide information.

The labels show up on the app’s page in the App Store, and you have to scroll down past several sections — past What’s New, Preview, and Ratings & Reviews — to get to them. Then you have to tap “see details” to get the full label. If you’re just updating an app that you’ve already downloaded to your device, you probably won’t even go to that app’s page to see the label.

“I think that they make it so easy to download that you don’t scroll down to read all of the fine print,” Tyana Soto, a packaging designer in New York, said. “I have never once scrolled down further than that download button. If it’s an app I really want, I don’t read all of the details or investigate further — which I’m now realizing I should.”

Reza Shamshad, a student from New Jersey, did know that the labels existed (he’s been waiting to check them out since they were first announced last June) and says he likes them, except for their placement.

“I fear the average consumer will not have any incentive to scroll down far enough to actually use them, given that one is primarily just interested in downloading the app quickly — especially if it’s free,” he said.

Even the simplest presentations can get complicated

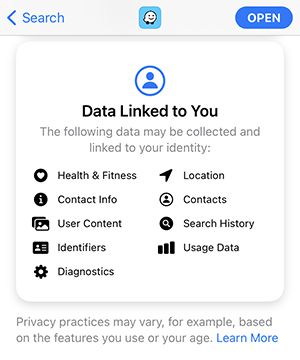

The labels are meant to be as easy to understand and as user-friendly as possible, but the app data collection industry is complicated and secretive. Data brokers want to collect as much information about you as possible (even data you didn’t even know it was possible to collect) without you realizing they’re doing it.

Apple’s labels have to strike a balance between giving the general user enough information to understand what an app is doing with their data, but not so much that the labels become as dense and complex as the privacy policies they’re supposed to summarize. When apps only collected a few types of data, that appears to work pretty well on the labels. But apps that collected a lot of data ended up with very long lists that people found to be less informative.

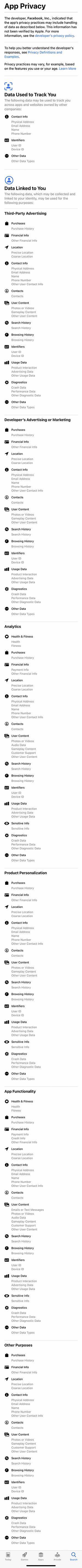

The privacy labels for the Facebook and Instagram apps, for instance, seemingly checked every data collection box that Apple offered. The result was a CVS-receipt-length privacy label that basically says Facebook may collect every category of data about you, including anything that doesn’t fall into a category. Here’s Facebook’s full label — get ready to scroll:

The labels of Facebook’s other apps — WhatsApp, Messenger, and Facebook Gaming — show that they also collect a lot of data, though they said they didn’t use it to track users, as Facebook and Instagram do. That’s an especially bad look for WhatsApp, which has promoted itself as a private, encrypted messaging app.

“Facebook had ‘other data types’ for all the categories of data,” Christine Sica, an account manager from Connecticut, said. “Anything not listed above could fall into that category of data they are collecting. They also use your physical address for all categories of data. I don’t ever recall giving out that information unless they base that on the location of your phone. It also appears they use ‘sensitive info’ for several categories. What constitutes sensitive info? Who would I even ask that question?”

According to Apple, sensitive info includes “racial or ethnic data, sexual orientation, pregnancy or childbirth information, disability, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, political opinion, genetic information, or biometric data.”

Sica wasn’t the only one who was confused over what data was being collected by the app without your permission and what could be collected only if you chose to provide it (or grant access to it). When Sica saw that Facebook collected audio data, she wondered if that meant the app was listening to her. But that’s only supposed to happen if you give Facebook audio permission and are actively using your microphone, for instance if you’re using Messenger’s Rooms feature for a video chat. Facebook isn’t listening to you beyond that (at least, that’s what the company and independent researchers say).

So you have some control over the collection of certain data, but you can’t stop Facebook’s apps from, say, collecting your device ID or IP address. That’s a distinction that might be worth making for users who want to know how and what they can control.

Some people also couldn’t figure out why certain categories of data were being collected from the labels alone. Waze’s label says it collects “Health & Fitness” information for app functionality, which was one of several reasons why Maria, a teacher from New York, found the labels to be “horrifying” — she couldn’t see how fitness information helped the app function, or what fitness information was being collected in the first place.

Waze told Recode that the purpose of this is to detect certain motion activity when a user parks their car. Taking Waze at its word, it’s not as creepy as the privacy label made it seem, but Maria couldn’t have known that from just the label.

Labels alone may not give you all the information you need

While the people I spoke to generally found the labels to be informative on a surface level, they weren’t sure what to make of them beyond that.

“Seemed easily understandable but then afterwards I found myself thinking, ‘Wait, what does that actually MEAN??’” said Sara Morrison (not me; my sister-in-law).

Apple likes to say that its labels are like food nutrition labels, but there is an important difference. While food nutrition labels put that information in context with the daily value percentage, Apple’s labels don’t make value judgments on whether certain data collection is good or bad, if an app is too invasive for the service it provides, or how it compares to other apps. You have to figure that out for yourself, and you may not have enough knowledge to really do that.

Davisson said he thought the labels could be most useful if someone were trying to decide which of two similar apps to download. The more privacy-centric app could get the edge there.

“I think it’s analogous to checking the forecast before you leave in the morning,” Davisson said. “If you see a 10 percent chance of rain, you might not bring your umbrella. If you see a 90 percent chance of rain, you might bring your umbrella. So if you’re looking at a side-by-side comparison and you see one app collects 50 categories of data and the other collects zero, that’s probably a good indication that that one is taking privacy seriously.”

So most people will have to read beyond the labels if they really want to know and understand what’s being collected and how. Here are two guides that should provide more clarity, or you can (shudder) read the app’s privacy policy.

You’re also relying on app developers to be honest about their data collection practices because, as the label says, Apple doesn’t verify them (the company says it does do audits, but those wouldn’t cover every single app). The developers have to submit the label when they upload a new app or update an existing one, and basically just check off the boxes that Apple provides. Citing concerns that developers may not be truthful, the US House Commerce Committee has asked Apple to explain how and when it audits the labels for accuracy. One person I talked to was surprised to discover that Google’s Gmail app had no label yet, because it hadn’t been updated in months.

That said, companies risk being kicked out of the App Store and getting in trouble with the Federal Trade Commission if they lie. You just have to hope that’s enough of an incentive for developers to be honest.

Labels aren’t perfect, but they’re useful

Despite the limitations, everyone I talked to was glad the labels were there, even if they didn’t personally learn anything new from them.

Several people said they would check the labels before downloading apps, now that they knew they existed and where they were. And some were sufficiently freaked out by what they saw on the labels that they adjusted some of their permissions and even deleted some of their apps.

Sascha Rissling, a web developer from Germany, told Recode he was “shocked” by how much information Twitter said it collected, so he deleted Twitter’s and Facebook’s apps from his phone. Several people told me that they turned off (or restricted) app access to their location data.

A few others were pleased to discover that certain apps collected a lot less data than they expected — for instance, Microsoft Solitaire Collection, Among Us, and True Coach. And then there’s Signal, the private messaging app that says it collects virtually nothing. When it comes to making users more aware, at least on a general level, of just how much data apps can collect about them, the labels seem to do the job.

But they also show just how much work consumers have to do if they want to minimize data collection. Everyone I talked to said that privacy was important to them, but many of them didn’t know what to do about it, or where and when it was being invaded, even after reading the labels. Some described privacy as an “uphill” or “losing” battle, and resigned themselves to having very little of it. And they’re not wrong.

They will, at least, have a little more control over some tracking when the iOS update that includes its App Tracking Transparency feature goes live sometime this spring. And it’s very possible the labels themselves will improve with time; Apple has said they are a work in progress.

“It should not be on the consumer to police all of this themselves, and to try to ascertain exactly what’s being collected, how it’s being used, and whether they find the developers’ representations trustworthy,” Davisson said. “We don’t expect people to regulate their own food supply; We should not expect individuals to regulate the use of their personal data by companies and third parties.”

Awareness is good, but empowerment is better. The labels promote the former. I’m not so sure about the latter.

Or, as Maria lamented: “This information has made me slightly more paranoid than I already am.”

Open Sourced is made possible by Omidyar Network. All Open Sourced content is editorially independent and produced by our journalists.