America’s billionaire philanthropists gave away more of their fortunes during the Covid-19 pandemic than they ever have before. But there’s a catch — one that underscores just how hard it is to follow the money in the world of mega-charity.

The 50 largest donors donated almost $25 billion to charity in 2020, according to the annual report from the Chronicle of Philanthropy, which offers the best yearly snapshot of the largest donations in America. Amid a historic health crisis that was a call to arms for the nonprofit sector — and during a renewed reckoning over racial inequities in the US — these billionaires made some of the largest donations they have ever made. These biggest donors gave away $16 billion in 2019.

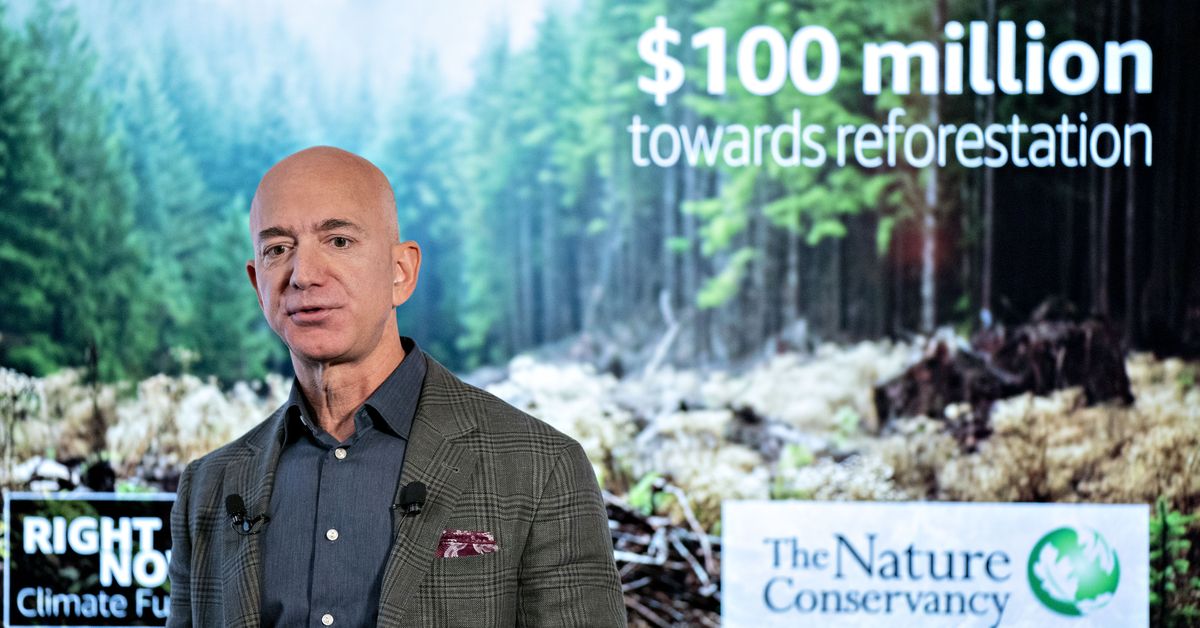

Jeff Bezos pledged $10 billion to combat climate change through the Bezos Earth Fund, one of the largest charitable commitments ever. MacKenzie Scott, Bezos’s ex-wife, donated almost $5 billion to hundreds of nonprofits. And Twitter founder Jack Dorsey set aside $1 billion worth of stock primarily to fund responses to the pandemic. 2020 was the first year with five $1 billion-plus commitments, according to the Chronicle (the other two came from former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg and Nike founder Phil Knight).

Every year, the Chronicle attempts to meticulously monitor gifts, and therefore plays a key role in informing our democracy on questions like the best way to solve income inequality and whether to raise taxes. The publication collects available records and interviews philanthropists’ aides. But its work has self-acknowledged limits that illustrate a bigger trend: The lack of transparency in the philanthropic sector makes it difficult to come to a common set of facts to even debate those policy questions.

For starters, the 50 biggest donors in 2020 would not have broken any records if the $10 billion commitment from Bezos — which is very different from the other donations — wasn’t included on the list. Bezos announced in February that he was promising that sum for grants but has not answered any details about the structure of that gift, including whether the commitment has been irrevocably set aside in some unique pool of money.

The reason that matters is because the Chronicle’s list doesn’t always focus on donations to nonprofits. It sometimes prioritizes donations to charitable vehicles — such as foundations that in turn donate to nonprofits — as part of an admirable attempt to avoid double-counting. The $10 billion promise to the Bezos Earth Fund is counted as a donation to a charitable vehicle.

But the fact is that we don’t even know where that $10 billion sits. Is the money actually placed in a charitable vehicle like a foundation, a donor-advised fund, or a limited liability company? Or is it more of a rhetorical pledge, similar to Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan’s commitment in 2015 to set aside 99 percent of their money to philanthropy (and which wasn’t counted on the list)?

We don’t know. Bezos’s representatives have consistently declined to share information on the Earth Fund’s structure. They didn’t return a Recode request for comment on Tuesday.

And if you excluded the Bezos pledge, this year’s headlines about American billionaires’ generosity during the pandemic would look a lot different.

“There are actually two related issues. One is that we don’t have a shared understanding of how to define and measure giving,” said Ben Soskis, a historian of big philanthropy. “The other is that a new crop of megadonors are embracing publicity in giving — but are doing so outside the bounds of traditional philanthropic organizations and so without any formal degree of accountability. The high profile philanthropic pledge is the embodiment of this problem. It divorces the moment of peak publicity from the opportunity for accountability.”

Alternatively, analysts for the Chronicle or elsewhere could look at the amount of money that actually went out the door to nonprofits directly in a year. Bezos would get credit for his Earth Fund donating $790 million to climate groups. The $350 million that Zuckerberg and Chan donated to support American election officials would now be included, rather than being ruled out as a double-count. Bill and Melinda Gates, one of America’s most consistent biggest distributors of cash, would mostly get credit for the roughly $5 billion that their foundation donates each year — rather than just being tagged with the estimated $160 million that they personally donated to their foundation in 2020.

There are pluses and minuses to that approach, which is taken by Forbes in its own philanthropy rankings: It would, in the eyes of some, rightly recognize philanthropists that get money out the door to nonprofits so that it could make a difference today, rather than parking the money in a financial warehouse in order to address some future problem. This different approach would also more accurately reflect billionaires’ true, consistent philanthropic work, instead of inflating their ranking if one year they make a large, lump-sum donation to a foundation, and deflating their ranking when they don’t match it the next year. It would, however, pose its own complications, such as who exactly should get credit for money distributed from foundations that have multiple funders.

But there’s a bigger point here. As these huge sums above make clear, a small change in these methods could very well change our conclusions about billionaire philanthropy.

This would all be for naught if philanthropy had a culture of transparency. Many philanthropists prefer to keep their donations anonymous, and some, like Bezos, seem to bristle at the notion of owing the public any information about their gifts (even though it offers tax advantages and can burnish their reputations). It would also be for naught if there were stronger legal requirements in the sector: Many billionaires use LLCs or donor-advised funds that don’t have to file tax documents that would spell out where their money comes from or what it is spent on. The private foundations that do have to file these tax documents don’t do so until over a year later — long after these rankings come out — and have their own accounting tricks.

And so we’re left with a patchwork system of transparency — dependent on what philanthropists voluntarily disclose and how exactly you choose to analyze the disclosures — that makes it almost impossible to objectively capture and understand billionaires’ charitable gifts.

The conclusion may very well be that the wealthiest people in the world donate more to charity than we think. Some major philanthropists who don’t choose to prioritize or publicize donation figures, such as Laurene Powell Jobs, have never appeared on the Philanthropy 50 over the past two decades.

But it’s essential to have a baseline of shared facts, because billionaire philanthropy is often used as a way to implicitly and explicitly justify American income inequality. Should there be a wealth tax? What types of charity should be tax-deductible? And, at a more basic level, does the US economy just plain work?

These are policy questions that people disagree on. But it’s hard to even stage the debate right now. So the figures and the headlines really matter — at least until the culture and the laws catch up.