Among the many grievances people harbor toward Elon Musk, add one more: alleged animal cruelty.

Neuralink, a startup co-founded by Musk in 2016, aims to develop a brain chip implant that it claims could one day help paralyzed people walk and blind people see. But to do that, the company has first been testing its technology on animals, killing some 1,500 since 2018 — and employee whistleblowers recently told Reuters the experiments are going horribly wrong.

Reuters reported this week that the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Inspector General has opened a probe into potential violations of the Animal Welfare Act at Neuralink. It’s a rare corrective for an agency that is generally hands-off when it comes to animal research.

Congressional Democrats are weighing in too. As reported by Reuters, US House Representatives Earl Blumenauer and Adam Schiff wrote in a draft letter to the USDA that they are “very concerned that this may be another example of high-profile cases of animal cruelty involving USDA-inspected facilities.”

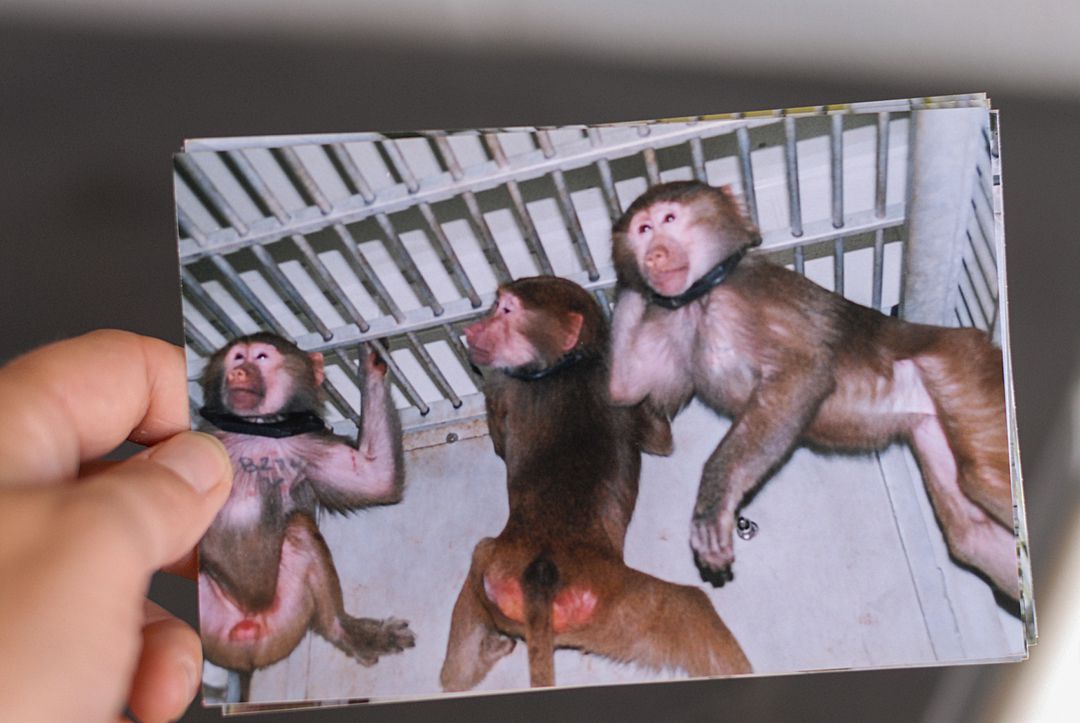

Questions around Neuralink’s treatment of animals date back to 2017, when Neuralink conducted experiments on monkeys at the University of California Davis. The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), a group that campaigns for alternatives to animal testing, obtained public records detailing the experiments. The findings were gruesome: One rhesus macaque monkey’s nausea was “so severe that the animal vomited and had open sores in her esophagus before she was finally killed,” according to Ryan Merkley, PCRM’s director of research advocacy.

Surgeons used an unapproved adhesive to fill open spaces in an animal’s skull, created from implanting the Neuralink device, “which then caused the animal to suffer greatly due to brain hemorrhaging,” Merkley said.

He also pointed to “instances of animals suffering from chronic infections, like staph infections where the implant was in their head. There were animals pulling out their hair and self-mutilating, which are signs of really poor psychological health in laboratory animals and are very common in rhesus macaques” and other primates. (Disclosure: My partner worked at PCRM six years ago and was colleagues with Merkley.)

A few years later, Neuralink moved its experiments in-house. Current and former employees told Reuters that Musk put staff under immense pressure to speed up animal trials in order to begin human trials, telling them that they had to imagine a bomb was strapped to their head as motivation to work harder and faster. That may have contributed to botched experiments: Through documents and interviews with Neuralink staff, Reuters identified four experiments with 86 pigs and two monkeys that went awry due to employee mistakes. As a result, the experiments had to be repeated. “One employee,” Reuters reported, “wrote an angry missive earlier this year to colleagues about the need to overhaul how the company organizes animal surgeries to prevent ‘hack jobs.’”

The breakneck speed at Neuralink likely caused researchers to test and kill more animals than a slower, more conventional approach would call for. Since 2018, the company has tested on and killed at least 1,500 animals — over 280 sheep, pigs, and monkeys, as well as mice and rats.

“There’s this incredible pressure by these Silicon Valley dudes who want their devices on the market, they want to push things forward, but they don’t understand that these things take time,” said Merkley. “That leads to — as we’ve seen — botched experiments and animals suffering.”

Neuralink did not respond to an interview request for this story. UC Davis declined an interview request and pointed me to its media statement on the issue.

“The research protocols were thoroughly reviewed and approved by the campus’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC),” one part of it reads. “When an incident occurred, it was reported to the IACUC, which mandated training and protocol changes as needed.” The university also said it “follows all applicable laws and regulations,” including those of the USDA and the National Institutes of Health.

In February, PCRM filed a complaint with the USDA alleging violations of the Animal Welfare Act stemming from the earlier Neuralink experiments at UC Davis. In March, the USDA posted inspection reports of both UC Davis and Neuralink facilities and found zero violations. But a federal prosecutor in the Northern District of California sent PCRM’s complaint to the USDA Inspector General (OIG), a federal office charged with investigating and auditing USDA programs, which then opened a formal probe, according to Reuters. When contacted, the USDA OIG responded “USDA OIG can neither confirm or deny any investigation.”

That the USDA found no violations at UC Davis or Neuralink “just shows you how weak the Animal Welfare Act is, and even more so how weak the enforcement of that law is,” Merkley said.

The USDA declined an interview request for this story but said in an emailed statement, “USDA takes its charge to enforce the AWA seriously, and works diligently every day to protect the welfare of regulated animals.”

The “move fast and break things” ethos of Silicon Valley can be dangerous enough when a company is building a new social network, but the stakes are far higher when the life and death of hundreds or thousands of animals is in question, let alone the human patients whom Neuralink hopes will be the ultimate recipients of its technology. But it would be a mistake to think of Musk and Neuralink as a mere bad apple. Cruel animal experiments are taking place not just at private medical companies, but also at universities, commercial research facilities, and government agencies across the country — and regulators are lagging behind.

The Animal Welfare Act, explained

As federal laws go, the 1966 Animal Welfare Act may have one of the weirder and darker origin stories. Starting in the 1940s, the demand for animal experimentation by federally funded scientists exploded, to the point where stray dogs were seized from animal shelters to serve as test subjects, while even pet dogs would sometimes be snatched up and sold to experimenters. The most high-profile case involved Pepper, a 5-year-old Dalmatian in Pennsylvania who went missing in the summer of 1964 and turned up nine days later at a New York City hospital, where she was used in a medical experiment and then cremated. Pepper’s fate — and a Life magazine exposé into dog experiments — caused an uproar. Two years later, Congress passed the Animal Welfare Act.

Despite its exhaustive-sounding name, the law excludes most animals kept in human captivity: the billions of animals we raise for food. It primarily covers the treatment and living conditions of companion animals bred in puppy mills, animals used for entertainment at zoos and circuses, and animals used in research for everything from vaccines to makeup. Even for these covered use cases, there are some big loopholes. Birds, reptiles, fish, and virtually all mice and rats — which make up the vast majority of animals used in vivisection — aren’t protected by the law, nor are animals used in agricultural research.

The Animal Welfare Act also doesn’t say much about what can and can’t be done to animals in experiments. Rather, it sets minimum standards for basic conditions such as food, water, space, and lighting.

The law leaves much of how experiments are conducted to bodies called Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees, or IACUCs. Most research facilities — private or public — must set up an IACUC, which means the research is essentially self-governed. IACUCs are usually composed of employees, in the case of private companies like Neuralink, or faculty at universities.

IACUCs do have some checks and balances — they must have at least one external member, inspect facilities every six months, and follow some record-keeping requirements, like submitting annual reports to the USDA and conducting literature reviews to minimize duplicative research. They’re also charged with minimizing pain in animals during procedures, among other requirements.

Those checks and balances still give scientists wide latitude to conduct research how they see fit, critics say, leading to many cruel and unnecessary experiments.

In 2014, the USDA’s Office of the Inspector General said some IACUCs “did not adequately approve, monitor, or report on experimental procedures on animals.”

One study that looked at a group of IACUCs found a 98 percent approval rate for experiment protocols, and other papers have found similarly high rates.

“There’s a tremendous problem if these IACUCs are populated just with the colleagues of the same institution,” said Thomas Hartung, a biochemist and the director of the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing at Johns Hopkins University. “In Europe, there’s a very different approach where there’s a separation of these bodies that are linked to competent authorities, where conflicts of interest are much more avoided. In general, the bar is much higher to get these experiments accepted.” He added that the more rigorous process leads to better science.

We don’t know the full scope of animal experiments or what exactly happens to the tens of millions of animals estimated to go under the knife in the name of science and product development each year. The USDA inspects each facility at least once a year and publishes those inspections, but they’re only a small snapshot of animal treatment. And labs accredited by AAALAC International, a private veterinary organization, benefit from only being subject to partial inspections. According to Science, 91 out of 322 facilities inspected during one period only received partial inspections.

It’s not uncommon for testing labs to fight to prevent details of experiments from coming to light (PCRM has sued UC Davis to hand over photos from the experiments under California’s public records law). But public records requests have exposed a number of disturbing experiments.

Wayne State University in Michigan has induced heart failure in dogs, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison deafened two cats with an antibiotic to study hearing implants, and the Department of Veterans Affairs implanted devices into cats’ skulls to study sleep disorders (one employee said it gave them nightmares). Last year, Vice reported on the mental health crisis among those who kill animals for science.

A Harvard researcher recently drew condemnation after publishing work about separating mother monkeys from their newborns and replacing them with stuffed animals, and suturing baby monkeys’ eyelids shut to study how they process faces.

There’s also the more mundane but cruel everyday practices, like keeping social animals, including mice and rats, in captivity for weeks, months, or years on end. It’s not uncommon for nonhuman primates to be caged alone, despite the USDA’s acknowledgment, back in 1999, that “… primates are clearly social beings and social housing is the most appropriate way to promote normal social behavior and meet social needs.” Routine toxicity tests required by the EPA force animals to inhale and ingest pesticides.

Even when Animal Welfare Act violations are found, researchers get off easy, according to Delcianna Winders, director of Vermont Law and Graduate School’s animal law and policy institute. The USDA can impose severe penalties against other enterprises governed by the Animal Welfare Act, including criminal charges, confiscating animals, revoking or suspending licenses, or applying for injunctions. But for research facilities, these are generally off the table (there’s a small caveat for confiscation). It’s what Winders calls “animal experimentation exceptionalism.”

Instead, violators might pay a settlement that’s a fraction of the maximum penalty. The USDA “typically offers to settle for a civil penalty that is much lower than the maximum civil penalty authorized in the relevant statute,” according to an agency FAQ. In a 2014 audit, the Office of Inspector General found that the USDA reduced penalties by an average of 86 percent from the AWA’s authorized maximum penalty per violation.

The USDA has also excluded certain violations from public reports. For the past six years, the agency had a policy called “Teachable Moments,” in which it refrained from including minor violations in public inspection reports (the policy ended this summer after years of pressure). Last year, the agency terminated a program that excluded some violations from public inspection reports if the research facility self-reported and corrected them.

In an emailed statement, the USDA said, “When inspectors identify items that are not in compliance with the federal standards, USDA Animal Care holds those facilities responsible for properly addressing and correcting those items within a set timeframe. If the noncompliance is not corrected, or if it is serious enough in nature, USDA pursues appropriate regulatory compliance and enforcement actions.”

The moral math of animal testing

Animal testing is often justified using a kind of moral math: It’s worth killing X number of animals if it leads to outcome Y, like helping paralyzed people walk or blind people see. But the problem is that we rarely know the number for X — it could take experimenting on one more animal, or millions more, for Neuralink to achieve its goal (even if Musk’s true goal is to use brain-computer interfaces to merge humans with AI). The same goes for inventing important new medical devices, pharmaceutical drugs, and vaccines. And of course, achieving outcome Y is almost always uncertain.

But moral math is hard to do if you’re missing half the equation. We have no idea how many animals are experimented on because federal agencies don’t keep a comprehensive tally. In fiscal year 2018, the USDA reported that 780,070 AWA-covered animals were used in experiments, with an additional 122,717 held in facilities but not used for research. But that number excludes birds, reptiles, and fish, as well as rats and mice, who make up the vast majority of animals used in experiments — over 99 percent according to veterinarian Larry Carbone, who estimates the US experiments on 111.5 million rats and mice per year (though some critics say this estimate is flawed).

Animal testing has led to scientific breakthroughs we all benefit from, but it’s also costly and slow, and it often fails — according to the NIH, 95 percent of pharmaceutical drugs that work in animal trials fail in human trials. But just how much humans benefit from animal experimentation is hard to parse: A 2018 meta-analysis from UK researchers looked at 212 studies from 1967 to 2005, involving over 27,000 animals, and concluded that most studies were poorly designed and didn’t meaningfully advance scientific knowledge. Only 3 percent of the studies mentioned pain relief for animals. Some in the science community wonder why we’re betting so much of the future of medicine on mice and rats.

Public opinion is changing on the issue, with the percentage of Americans who support medical animal testing dropping from 65 percent in 2001 to 51 percent in 2017. There’s also a growing chorus of voices — not just activists and law professors, but also drug developers, researchers, veterinarians, and entrepreneurs — arguing that a new suite of high-tech, non-animal alternative methods could lead to faster, safer, and more ethical drug development and product testing.

“There has been, over the last 40 years, an enormous change,” said Hartung. “Alternative methods are as good or better than animals in many areas.”

Musk has always viewed himself as a change agent, a disruptor, and Neuralink is part of that. But in allegedly mistreating animals in research, his company is all too conventional.

<div class="c-article-footer c-article-footer-cta" data-cid="site/article_footer-1670763617_5136_165758" data-cdata="{"base_type":"Entry","id":23264198,"timestamp":1670760000,"published_timestamp":1670760000,"show_published_and_updated_timestamps":false,"title":"Neuralink shows what happens when you bring “move fast and break things” to animal research","type":"Feature","url":"https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2022/12/11/23500157/neuralink-animal-testing-elon-musk-usda-probe","entry_layout":{"key":"unison_default","layout":"unison_main","template":"minimal"},"additional_byline":null,"authors":[{"id":6907975,"name":"Kenny Torrella","url":"https://www.vox.com/authors/kenny-torrella","twitter_handle":"KennyTorrella","profile_image_url":"https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/thumbor/HEYPm5ktzDxAFF8FOnFeoXT9JKM=/512×512/cdn.vox-cdn.com/author_profile_images/195969/Torrella_Headshot.0.png","title":"","email":"","short_author_bio":"is a staff writer for Vox’s Future Perfect section, with a focus on animal welfare and the future of meat."}],"byline_enabled":true,"byline_credit_text":"By","byline_serial_comma_enabled":true,"comment_count":0,"comments_enabled":false,"legacy_comments_enabled":false,"coral_comments_enabled":false,"coral_comment_counts_enabled":false,"commerce_disclosure":null,"community_name":"Vox","community_url":"https://www.vox.com/","community_logo":"rnrn rn

rnrnReader gifts support this mission by helping to keep our work free — whether we’re adding nuanced context to events in the news or explaining how our economy got where it is. While we’re committed to keeping Vox free, our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism does take a lot of resources, and gifts help us rely less on advertising. We’re aiming to raise 3,000 new gifts by December 31 to help keep this valuable work free. Help us reach our goal

Reader gifts support this mission by helping to keep our work free — whether we’re adding nuanced context to events in the news or explaining how our economy got where it is. While we’re committed to keeping Vox free, our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism does take a lot of resources, and gifts help us rely less on advertising. We’re aiming to raise 3,000 new gifts by December 31 to help keep this valuable work free. Will you help us reach our goal and support our mission by making a gift today?

Yes, I’ll give $120/year