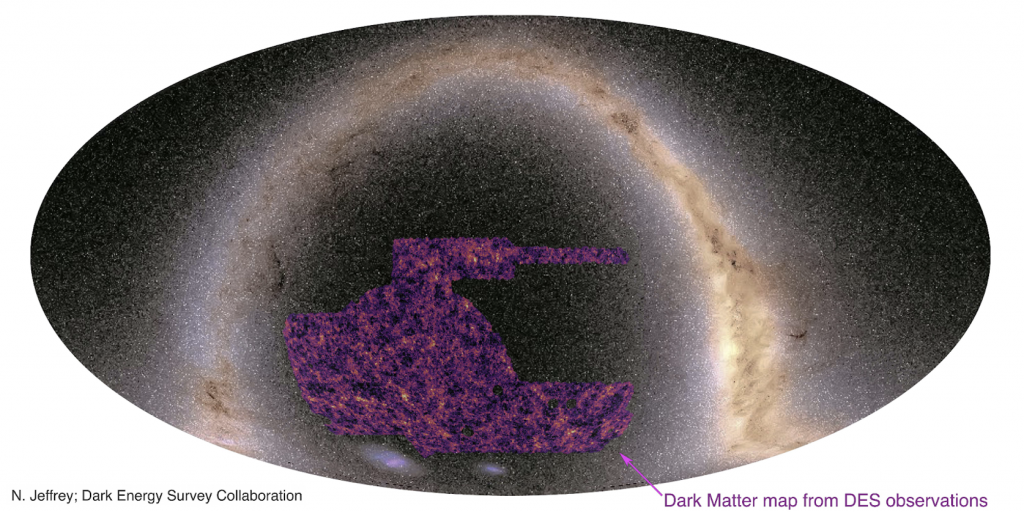

The DES is an effort to image as many galaxies as possible as a proxy for mapping out dark matter, which is possible because dark matter’s gravity plays a strong role in governing how these galaxies are distributed. From August 2013 to January 2019, dozens upon dozens of scientists came together to use the four-meter Victor M. Blanco Telescope in Chile to survey the sky in near infrared.

There are two keys to creating the map. The first is simply observing the location and distribution of galaxies throughout the universe. That arrangement clues scientists in to where the largest concentrations of dark matter are located.

The second is observing gravitational lensing, a phenomenon in which the light emitted by galaxies is gravitationally stretched by dark matter as it moves through space. The effect is similar to looking through a magnifying glass. Scientists use gravitational lensing to infer how much actual space nearby dark matter is taking up. The more distorted the light, the clumpier the dark matter.

The latest results take into account the first three years of DES data, tallying more than 226 million galaxies observed over 345 nights. “We are now able to map out dark matter over a quarter of the Southern Hemisphere,” says Niall Jeffrey, a researcher from University College London and École Normale Supérieure in Paris, one of the DES project leads.

DARK ENERGY SURVEY

In general, the data lines up with the so-called Standard Model of Cosmology, which posits that the universe was created in the Big Bang and that its total mass-energy content is 95% dark matter and dark energy. And the new map provided scientists with a more detailed look at some vast dark-matter structures of the universe that otherwise remain invisible to us. The brightest spots on the map represent the highest concentrations of dark matter, and they form clusters and halos around voids of very low densities.

But some results were surprising. “We found hints that the universe is smoother than expected,” says Jeffrey. “These hints are also seen in other gravitational-lensing experiments.”

This is not what is predicted by general relativity, which suggests that dark matter should be more clumpy and less uniformly distributed. The authors write in one of the 30 papers being released that “though the evidence is by no means definitive, we are perhaps beginning to see hints of new physics.” For cosmologists, “this would correspond to possibly changing the laws of gravity as described by Einstein,” says Jeffrey.

Although the implications are huge, caution is paramount, because we still actually know so little about dark matter (something we’ve yet to directly observe). For example, Jeffrey notes that “if nearby galaxies form in an alignment in a strange way due to complex astrophysics, then our lensing results would be misled.”

In other words, there might very well be some exotic explanations for the results—perhaps accounting for them in ways that are reconcilable with general relativity. That would be a huge relief to any astrophysicist whose entire life’s work is based on Einstein being, well, correct. And let’s not forget: general relativity has stood up remarkably well to every other test that has been thrown at it over the years.

The results are already making waves, even with several more DES data releases pending. “Already, astronomers are using these maps to study the structures of the cosmic web and understand the connection between galaxies and dark matter better,” says Jeffrey. We may not have to wait too long to find out whether the results really are a blip or our understanding of the universe needs some massive rewriting.