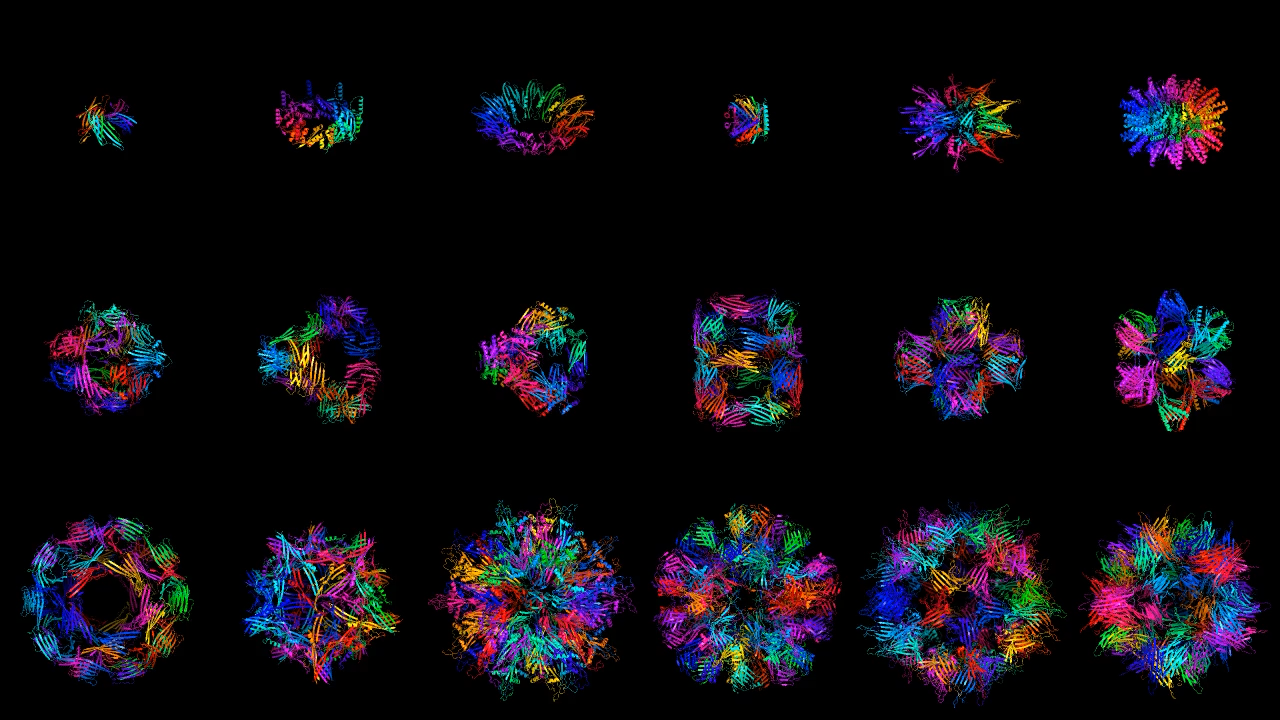

Today, two labs separately announced programs that use diffusion models to generate designs for novel proteins with more precision than ever before. Generate Biomedicines, a Boston-based startup, revealed a program called Chroma, which the company describes as the “DALL-E 2 of biology.”

At the same time, a team at the University of Washington led by biologist David Baker has built a similar program called RoseTTAFold Diffusion. In a preprint paper posted online today, Baker and his colleagues show that their model can generate precise designs for novel proteins that can then be brought to life in the lab. “We’re generating proteins with really no similarity to existing ones,” says Brian Trippe, one of the co-developers of RoseTTAFold.

These protein generators can be directed to produce designs for proteins with specific properties, such as shape or size or function. In effect, this makes it possible to come up with new proteins to do particular jobs on demand. Researchers hope that this will eventually lead to the development of new and more effective drugs. “We can discover in minutes what took evolution millions of years,” says Gevorg Grigoryan, CEO of Generate Biomedicines.

“What is notable about this work is the generation of proteins according to desired constraints,” says Ava Amini, a biophysicist at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

GENERATE BIOMEDICINES

Proteins are the fundamental building blocks of living systems. In animals, they digest food, contract muscles, detect light, drive the immune system, and so much more. When people get sick, proteins play a part.

Proteins are thus prime targets for drugs. And many of today’s newest drugs are protein based themselves. “Nature uses proteins for essentially everything,” says Grigoryan. “The promise that offers for therapeutic interventions is really immense.”

But drug designers currently have to draw on an ingredient list made up of natural proteins. The goal of protein generation is to extend that list with a nearly infinite pool of computer-designed ones.

Computational techniques for designing proteins are not new. But previous approaches have been slow and not great at designing large proteins or protein complexes—molecular machines made up of multiple proteins coupled together. And such proteins are often crucial for treating diseases.