Amazon, Apple, Chipotle, REI, Starbucks, Trader Joe’s. It feels like every day brings a new, surprising union.

Workers are organizing at some of the most well-known companies in America and in industries previously thought un-unionizable. They’re also doing so against the tide of a decades-long decline in union membership, which led to eviscerated benefits and wages that haven’t kept pace with the cost of living. Lately, the news has been filled with stories of everyone from baristas to warehouse workers voting for unions and bargaining for contracts — a trend that makes it look like unions are at last on the rise again.

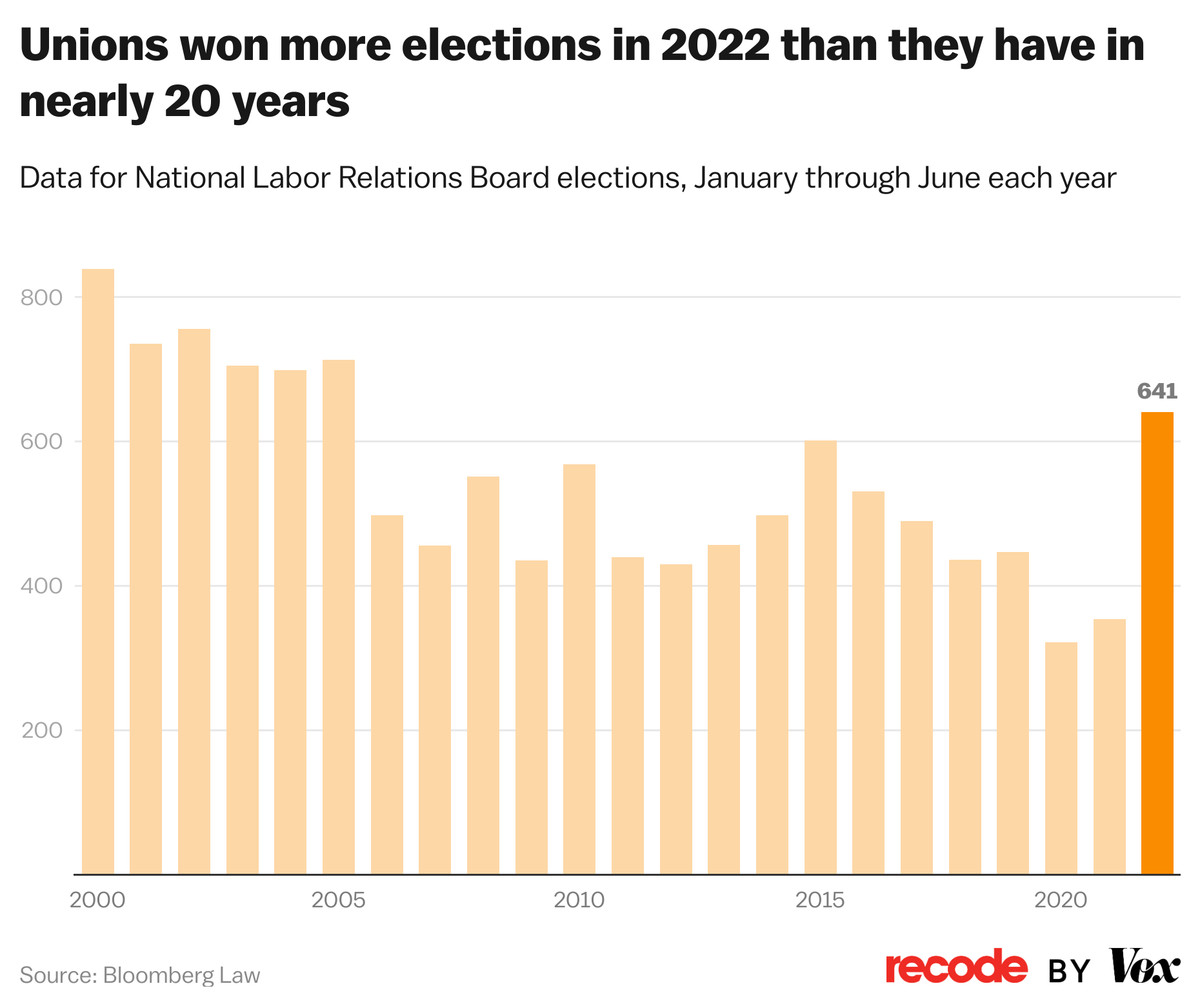

Indeed, a series of recent data suggests that these union gains are more than just headlines. From election wins to collective actions, 2022 has so far been a great year for unions. In the first half of the year, unions won 641 elections — the most in nearly 20 years, according to data from Bloomberg Law, which analyzes National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) data.

And while union wins at household names like Starbucks, which has had more than 230 stores unionize this year, are certainly adding to the total, they’re not the only thing driving union growth. As Bloomberg Law’s Robert Combs pointed out, even without the coffee chain, 2022 still would have beaten last year’s numbers. Retail, service, health care, and transportation industries all saw growth in union formations this year.

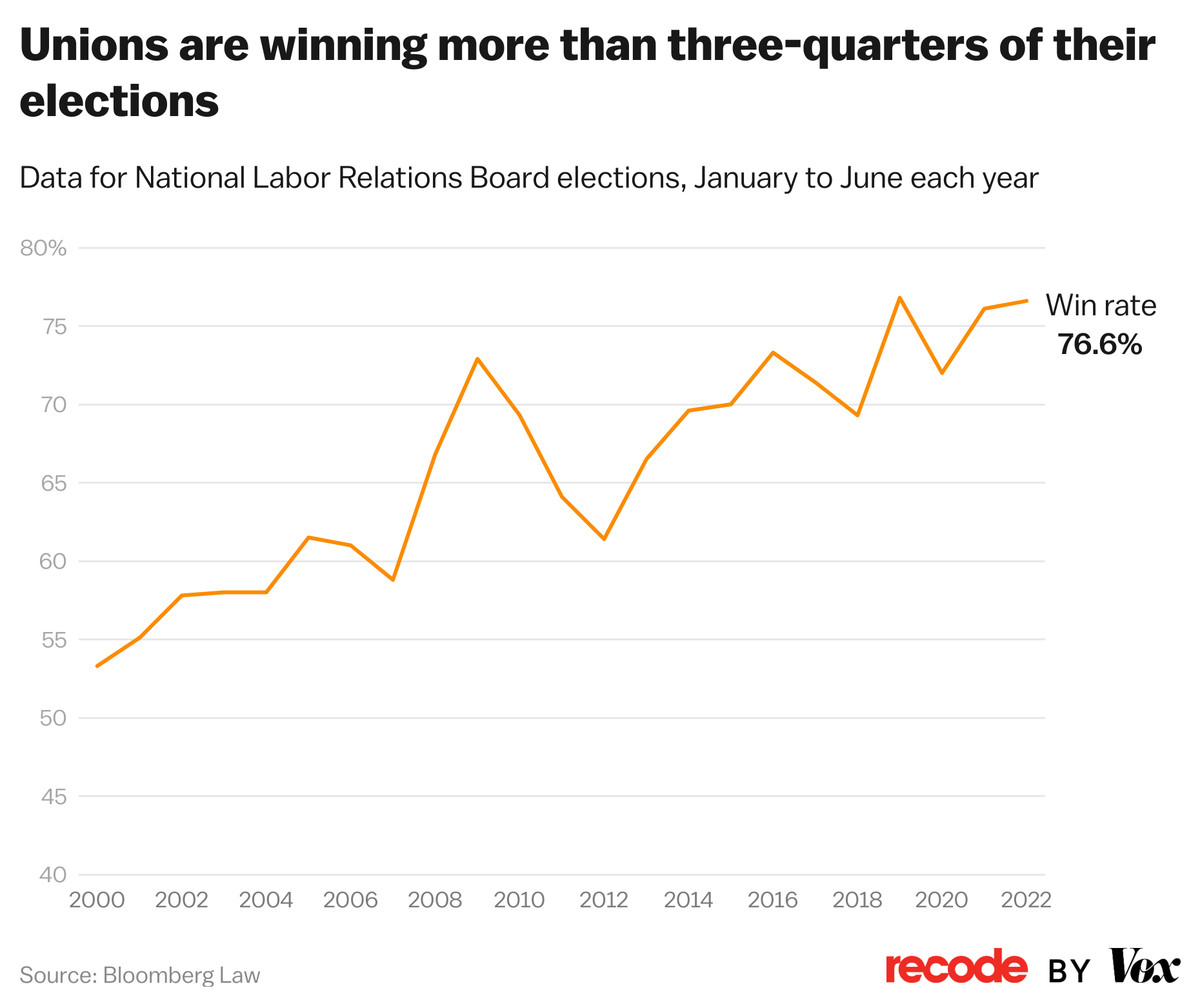

In total, there were 80 percent more NLRB election wins in 2022 than there were in 2021, and those wins represent more than twice as many workers — 43,150 — as last year. Unions have won nearly 77 percent of their elections this year, matching the highest rate in the Bloomberg data going back to 2000.

Petitions for future elections were up nearly 60 percent in the first nine months of the fiscal year, according to the NLRB, so expect more elections — and potential wins — to come in the second half.

Experts credit the rise in union organizing, in part, to the pandemic. During the global crisis, many of the companies that have since unionized called their employees “essential workers” but didn’t treat them that way when it came to wages, benefits, and safety. The situation galvanized workers to organize, but they have a long way to go before they reap the rewards.

For a union to deliver on its promises, workers must bargain and agree on a contract with their employer, which is no simple task if employers don’t cooperate. Starbucks, for example, has been using a whole host of tactics to delay bargaining. So far, the company has begun bargaining with just three of the more than 230 Starbucks stores that have unionized.

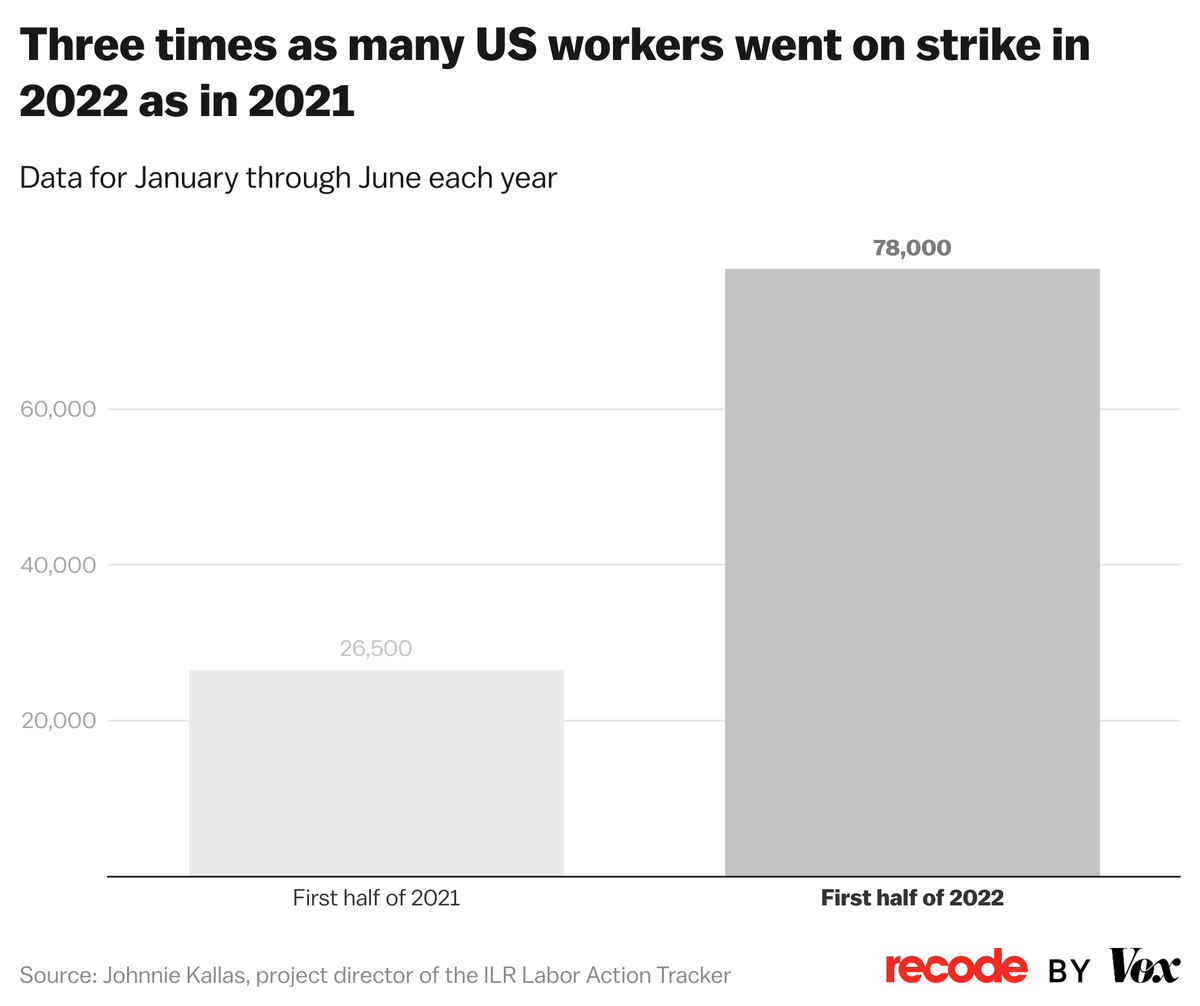

To get companies to bargain in good faith, unions will likely have to turn to collective actions, like strikes. That’s already happening.

There were 180 strikes in the first half of this year, which is up 76 percent compared with last year according to data provided to Recode by Johnnie Kallas, project director of Cornell’s ILR Labor Action Tracker. More impressively, those strikes included three times as many people as last year. These actions have the dual purpose of getting unions what they want from their employers and elevating their plight to the public.

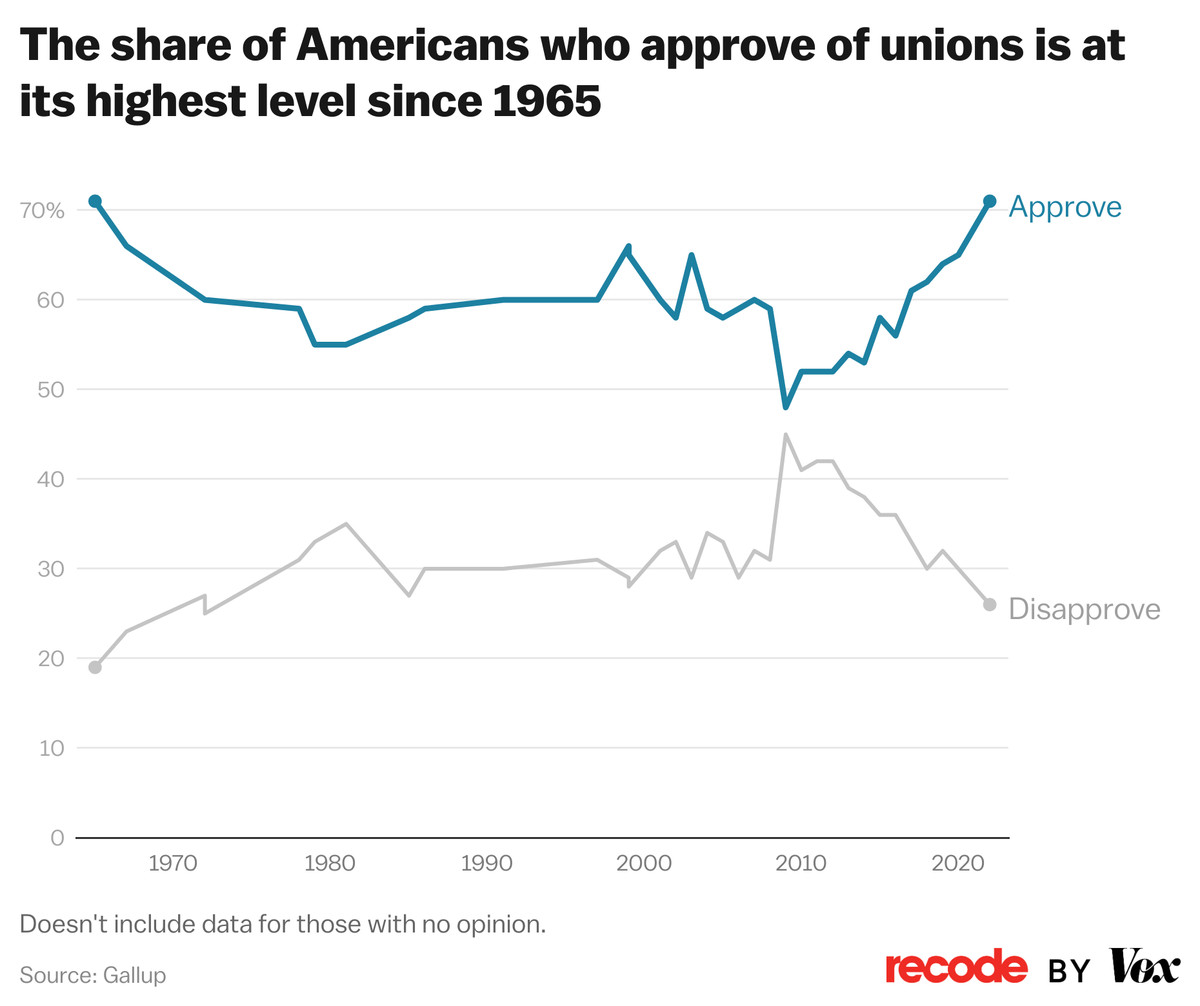

In general, the rise in union organizing is happening amid — and perhaps contributing to — increased approval of unions. Some 71 percent of Americans approve of unions in 2022, according to new survey data from Gallup. The last time union approval was that high was in 1965, when union membership rates were more than two times higher than they are now.

Whether this high approval leads politicians to enact reforms that would make unionizing less onerous in the first place remains to be seen. For now, all signs point to unions doing the best they can in the current situation.