The US coal industry is in a long-term decline, and the recent Supreme Court ruling in the West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency case won’t change that.

The case centers on a 2015 EPA regulation called the Clean Power Plan aimed at limiting greenhouse gases from power plants. The rule never went into effect, as it was halted by the Supreme Court in 2016, then replaced under President Donald Trump with a weaker regulation, which in turn was struck down by a federal court in 2021.

However, the 6-3 ruling on party lines drastically limits the EPA’s ability to form new regulations that have broad economic or political implications. That will likely include rules such as the Biden administration’s proposal to regulate power sector emissions, due out later this summer.

The court’s decision is part of a coordinated years-long legal effort by conservatives to undermine federal regulations. But weakening climate change policies aren’t enough to restore King Coal to its throne, a fact that the industry has begun to acknowledge. “There is no question that US thermal coal is a challenged market, and one that is in secular decline,” said Glenn Kellow, CEO of Peabody Energy, the largest coal-mining company in the US, during an earnings call last year.

The forces behind coal’s downfall will likely get stronger in the coming years, yet its decline could still slow down as broader shocks to the economy hamper its competitors. Coal will likely continue to lose ground, but that may not be enough to meet the United States’ climate change goals.

Economics are hurting coal more than regulations

The reason coal has been steadily losing ground has more to do with economics than regulations. And the Supreme Court can’t change the fact that most of the nation’s coal fleet is too old, too expensive, and too inefficient to keep running indefinitely.

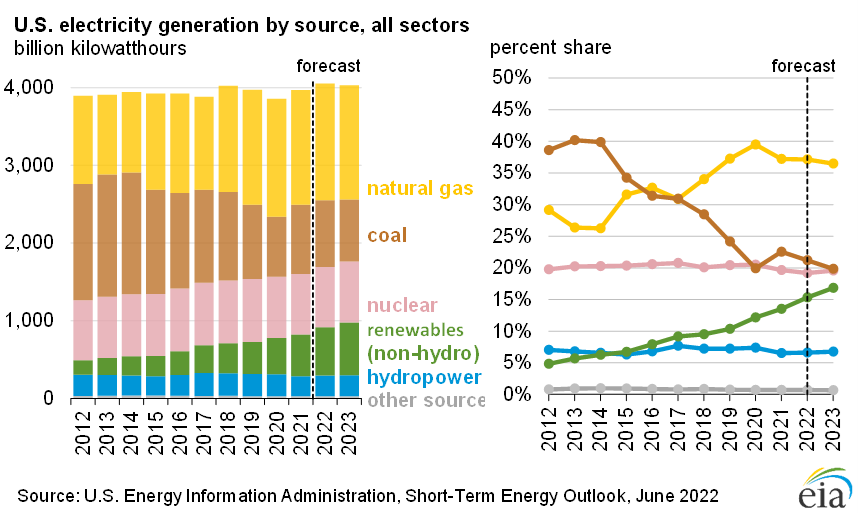

In the US, coal provides about 21 percent of electricity yet accounts for more than half of all carbon dioxide emissions from power production, making it one of the dirtiest fossil fuels.

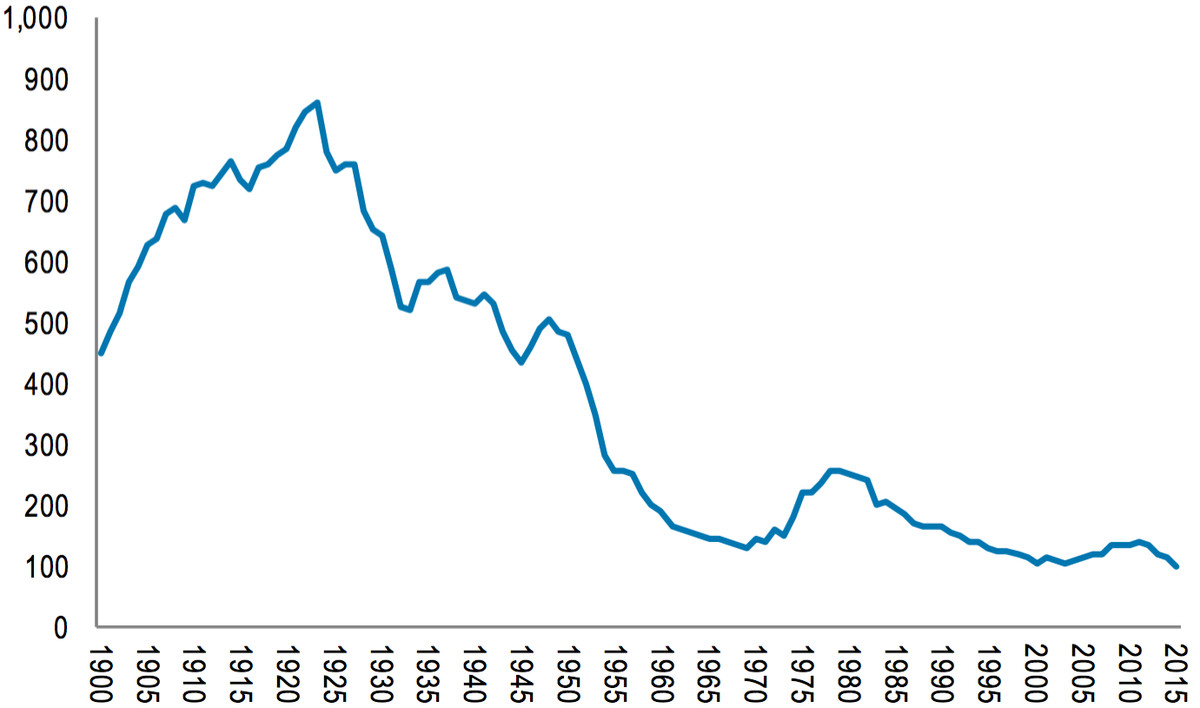

Its share of the power sector peaked in 2013 and has shrunk ever since. The coal industry’s labor force has seen an even more dramatic decline, falling to under 40,000 employees in 2022, a tiny fraction of its all-time high a century ago.

However, coal output still grew for much of the 20th century as mechanization and automation let fewer workers mine more, with output peaking in 2006. But by 2020, coal production in the US fell to its lowest levels since 1965.

There are several factors behind this. Power plants that burn coal are aging, with many built in the 1970s and 1980s and now closing in on retirement. This year, 14.9 gigawatts of electricity capacity is scheduled to retire, with 85 percent of shutdowns coming from coal-fired generators. A decade ago, the power sector was the biggest source of greenhouse gases in the country. It’s in second place today — 25 percent versus transportation’s 27 percent — simply because of coal’s decline.

Another big factor in coal’s demise is competition, chiefly cheap natural gas driven by hydraulic fracturing over the past decade. While natural gas has grown to supply most of the nation’s energy, solar and wind are racing upward too. Renewables are now the fastest-growing energy source in the US. The sector, including hydropower, accounted for 20 percent of generation in 2021, and the US Energy Information Administration expects it to grow to 24 percent by 2023. Wind provides 9.2 percent of electricity and solar 2.8 percent. These generators will account for most utility-scale growth in the coming years. In some parts of the world, building new renewable energy generators costs less than running existing coal plants.

Some regulations have also accelerated coal’s downfall, namely an Obama-era rule targeting mercury and sulfur emissions from coal plants. Back in 2011, when the regulation came out, the EPA didn’t have climate regulations in place yet for existing power plants, but coal-fired generators would have had to upgrade their pollution controls. At the time, it just wasn’t worth it to keep the oldest plants in the country running with expensive new equipment when gas was already far cheaper. That rule was delayed by the Supreme Court in 2015 and rolled back by Trump in 2018, but it still sped along some coal power plant closures.

Coal retirements only accelerated under Trump — despite his cabinet being stacked with coal backers, including Andrew Wheeler, a former coal lobbyist and Trump’s EPA chief. Yet even with so many industry advocates in power, the Trump administration couldn’t stop the inevitable. Despite its campaign to subsidize the Navajo Generating Station coal plant in Arizona, the largest in the western US, the plant and its nearby coal mine still closed in 2020.

The question now is how quickly coal will decline

Though the overall trend is downward, coal did see a resurgence during the Covid-19 pandemic due to rising natural gas prices. This slowdown in coal’s decline only makes it harder for the US to meet its climate change targets. Last year, President Joe Biden committed to cut US greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent relative to 2005 levels by 2030, but US carbon dioxide pollution rose instead.

So economics alone are not a reliable way to meet climate targets, and the rate of fossil fuel-powered generator shutdowns will have to speed up. Yet the Sierra Club counts 173 remaining coal plants in the US without plans to retire. Some plant operators have even sought bailouts, and utilities propped up money-losing coal plants with rate hikes on customers.

If the US has any chance of slashing its climate pollution drastically by 2030, every one of these plants would need to retire by then.

Activists are certainly trying. The Sierra Club, through its Beyond Coal campaign, has been working to accelerate coal’s downfall, making the case in local hearings and public meetings that coal power is dangerous and harmful. The campaign has led to coal plant shutdowns across the US and thwarted new plants.

Still, greenhouse gas emissions are not falling fast enough, and if environmental regulations get weaker, the dirtiest sources of energy may hang around longer. With energy prices surging and inflation growing during an election year, addressing climate change has become a lower priority. Getting on course demands a deliberate set of policies, like a clean electricity standard, but Congress is unlikely to pass any such measures this year. With its recent ruling to limit the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases, the Supreme Court is throttling another important avenue to limit the warming of the planet. But for the US coal industry, it is far too little and much too late.