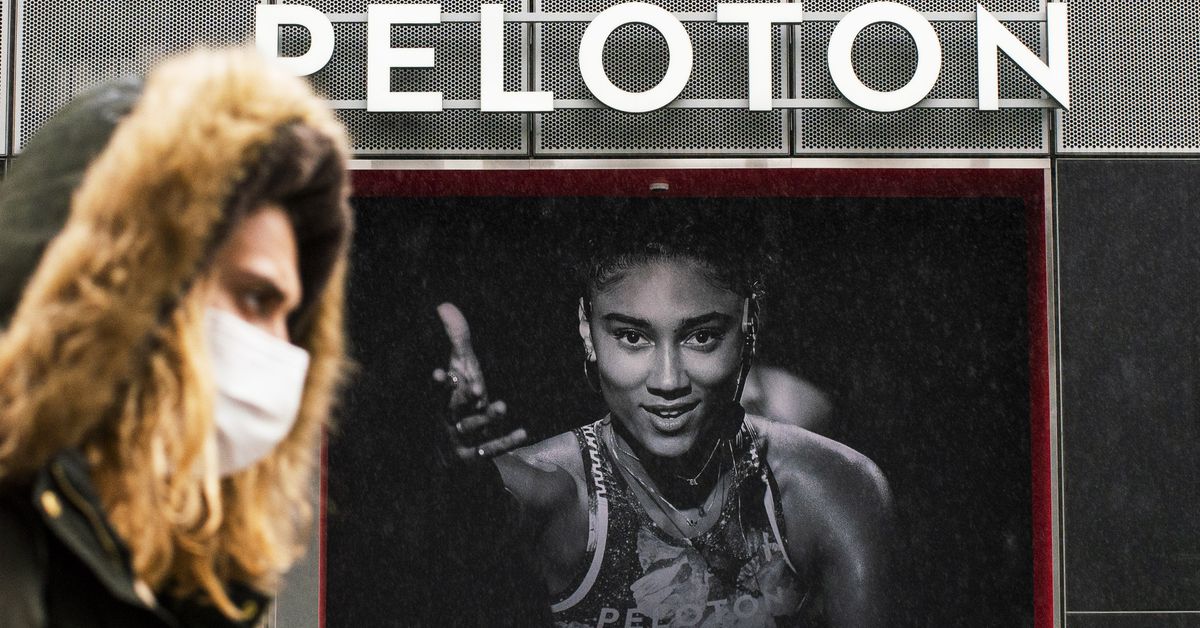

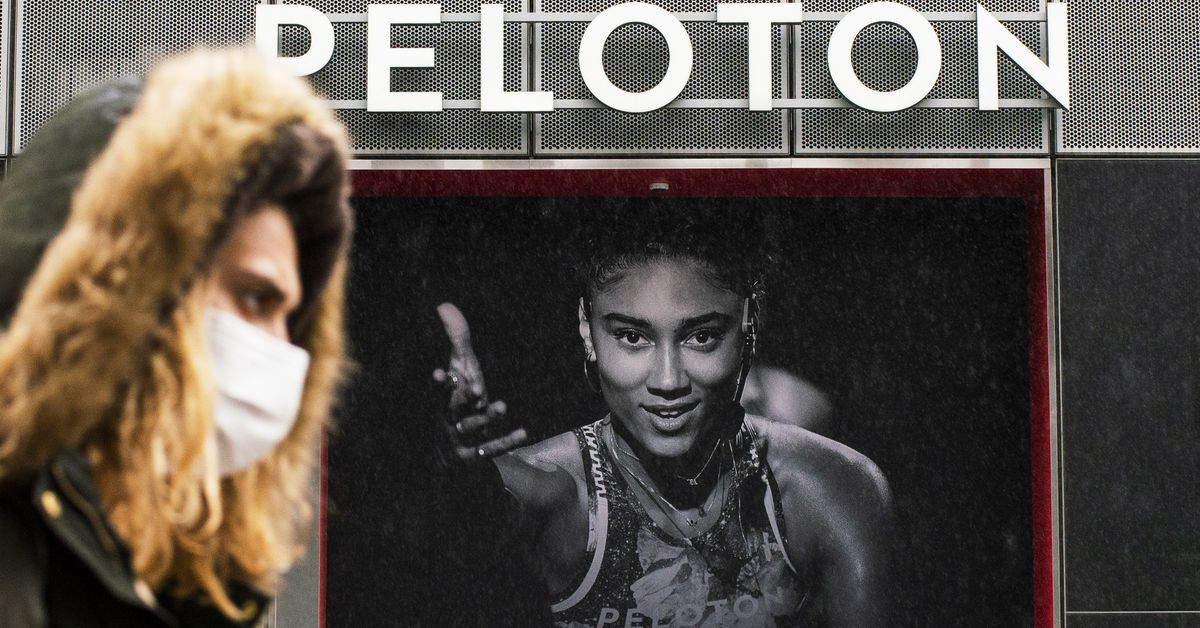

Peloton is spiraling, and its downfall could be a harbinger of real trouble for an entire industry. The at-home digital exercise company is one of several that thrived during the pandemic and promised to change forever how we work out. But now, it’s not clear if they’ll be around to finish the at-home fitness revolution they started.

There’s no denying that the pandemic made working out at home extremely popular. After gyms were forced to close their doors, people canceled their memberships and invested in exercise equipment and online class subscriptions instead. So much so that companies like Peloton couldn’t keep up with demand, leaving many customers to wait months for their bikes and treadmills to be delivered. But Covid-19 restrictions didn’t last forever. Eventually, when gyms started reopening, people stopped buying — and using — exercise equipment with the same enthusiasm they had in the spring of 2020.

Many of the issues Peloton faced were specific to the company. Some investors had argued that Foley — who led the company for a decade — just wasn’t up to the task of scaling the company so quickly. Peloton also had a series of slip-ups, including supply chain problems, a very public recall of its treadmills, and a controversial ad campaign.

But Peloton’s demise also coincides with a trend in more people working out like they used to do: at gyms. Demand for in-person fitness classes and gym memberships has rebounded, while Google searches for home gym equipment overall have continued to fall since their high in March of 2020. Foot traffic to gyms has now returned to the same levels as January 2020, according to data from SafeGraph, a geospatial data company. Planet Fitness alone said that, by November, it had recovered 15 million customers, which amounts to just half a million customers less than its pre-pandemic peak.

In the wake of the return to gyms, Peloton’s competitors are starting to see signs of trouble, too. Mirror is one of them. The company sells a $1,495 smart mirror that streams virtual exercise classes on the surface of the device as you work out. Just a few months into the pandemic, Lululemon bought Mirror for $500 million in a bid to capitalize on the big transition to at-home fitness. Over a year later, the athleisure brand has cut its estimated revenue expectations for Mirror in half.

“As you know, 2021 has been a challenging year for digital fitness,” Lululemon CEO Calvin McDonald told investors in December. “We have seen increasing pressures on customer acquisition costs that are impacting the entire industry.”

Meanwhile, NordicTrack’s parent company, iFIT, announced that it would go public last September, but a month later, it delayed the move, citing “adverse market conditions.” And Nautilus, which owns fitness brands like Bowflex and Schwinn, also reported late last year that some of its products haven’t been selling as well as they did earlier in the pandemic, though many are still more popular than they were back in 2019.

It’s possible that Peloton could find a path forward if a larger company acquires it. But there are reasons to believe that won’t happen, even with its new CEO. Some activist investors want a larger company to buy Peloton and have suggested at least 19 possible candidates, including Apple, Netflix, and Lululemon. But these companies may not be interested in an expensive but niche fitness business. Apple, for instance, is already wary of buying more companies and catching the attention of antitrust regulations. Netflix isn’t in the device business, and the streaming giant has generally avoided fitness content. Lululemon already has Mirror.

But as Peloton searches for a buyer, plenty of other companies are building streaming platforms for fitness content that allow people to use any equipment they want — and for a lot less money. These services include Apple’s Fitness+, on-demand home workouts from ClassPass, and millions of fitness videos on YouTube. These streaming options tend to make money through advertisements or low-cost monthly subscriptions without pushing people to buy specialized equipment.

Whether other companies will go the way of Peloton remains to be seen. Of course, this would hardly be the first time an at-home fitness fad has come and gone. Every generation of tech seems to come with its own spin on the home fitness revolution, from VHS aerobics to the exercise equipment sold on QVC. This time around, Peloton thought streaming and touchscreens would be the breakthrough to keep people hooked. Unfortunately for Peloton, the company may have just built another expensive clothing rack.

This story was first published in the Recode newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one!