Best Buy has revealed a curious way to cash in on worldwide shortages and shipping delays: subscriptions. This week, the company announced a $200-a-year program that promises consumers lower prices and exclusive access to hard-to-find devices. While the new membership also includes 24/7 tech support and free shipping, the idea of guaranteed product availability might be particularly appealing to shoppers worried that their orders won’t arrive in time for the holidays.

The new Best Buy service is a stark reminder that retailers don’t anticipate that supply chain issues, including the global semiconductor chip shortage, are going away anytime soon. In fact, it looks like they’re getting worse. A supply crunch for petrochemicals, which are used in everything from paint to plastics, has raised the prices on all kinds of products. Meanwhile, an emerging energy crunch in China has led to power cuts that have closed factories and disrupted daily life there. These recent developments are compounding the existing problems with the global supply chain and making logistical bottlenecks worse. Combine that with an ongoing shortage of shipping containers and truck drivers, and the end result is a huge slowdown in the delivery of goods.

“You’ve got labor-related issues. You’ve got issues of lack of availability of empty containers and space on vessels. Port congestion here in the United States, workforce issues with trucker availability and warehouse workers,” Jon Gold, a vice president for supply chain and customs policy at the National Retail Federation, told Recode. “The entire system has been stretched.”

While retailers are racing to import the goods and gadgets they think consumers will want during the holiday shopping season, the growing list of shortages has made it difficult for them to find enough stock. Now, experts say consumers should expect higher prices, delays, and opportunistic resellers as Black Friday and Cyber Monday draw closer. And for the next six months to a year, we just won’t see the same variety of products that we’re used to, according to Patrick Penfield, a supply chain professor at Syracuse University.

Supply chain problems are getting worse

Gadgets are particularly vulnerable to shortages because they include many different components. Consider all the parts that go into a PlayStation 5 or a new laptop, including their chips, outer shells, and screens. Many of these components require their own specialized manufacturing facilities, which are typically in different factories and often in different countries. For a device to be delivered on time, all of these parts need to be made in sync. Right now, that’s not happening.

“A lot of people who are working on this don’t really understand how diverse all the components that go into supply chains are,” Willy Shih, a business administration professor at Harvard, told Recode in August. “They don’t understand that I need capacitors. They don’t understand that I need power management chips. They don’t understand that I need inductors.”

Demand for these components has run up against efforts to contain Covid-19 in the countries where the production and assembly of many goods actually take place. Amid a recent delta variant outbreak and nationwide lockdown in Malaysia, the government designated electronics manufacturers critical businesses so that production could continue. In May, Vietnam directed vaccines directly to factory workers, while urging smartphone manufacturers working in the country, like Samsung, to do the same. (Vietnam’s Covid-19 challenges haven’t gone away: This past weekend, tens of thousands of workers fled the country’s commercial center after the government, which is still struggling to access vaccines, lifted pandemic lockdown restrictions.)

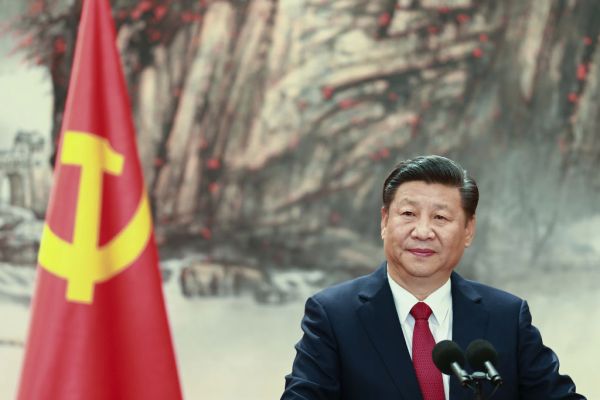

Now, planned power outages aimed at curbing energy use in China are making electronics manufacturing increasingly complicated. The situation is a consequence of several interwoven problems, including a global surge in fossil fuel prices; a dispute between China and Australia, which is one of the country’s main suppliers of coal; and China’s efforts to curb pollution ahead of the Winter Olympic Games. The resulting electricity cuts have had a devastating effect on people’s daily lives and left some homes and classrooms without power and water.

China’s energy crunch has also forced many factories, including those that build components for Apple, Dell, Tesla, and Microsoft, to pause or cut down on production. Meanwhile, appliance manufacturers and automakers in the country are bracing for a shortage of metal after metal smelters limited operations. Power shortages are likewise hindering companies responsible for things like chip packaging, chip testing, and phone assembly.

On top of all this, the shortage of petrochemicals, which are derived from oil, has made it more difficult and expensive to produce all sorts of goods, including paint, adhesives, and food packaging. In recent weeks, the price of polyvinyl chloride, a chemical used to make plastic, has surged 70 percent. Without those raw materials, makers of everything from credit cards to medical devices to cars are having an even harder time keeping up production.

“What will happen is that a phone will be delayed because they’re waiting on their plastic supplier, and the plastic supplier is waiting on the ingredient,” Penfield, the Syracuse professor, said. “It just takes one supplier — and it could be the base ingredient supplier — to fully screw up your supply chain.”

The disruptions in petrochemical manufacturing have many causes, but some are linked to companies that still haven’t recovered from the winter storm in Texas and several recent hurricanes along the Gulf Coast. This correlation shows how extreme weather exacerbated by climate change is having unanticipated ripple effects across many industries.

Rethink the holiday season

All these problems mean that consumers are seeing rising prices and shipping delays for a wide range of products. So those looking ahead to the holiday shopping season might want to get an early start, and not just on consumer electronics. As Vox’s Terry Nguyen reported last month, almost everything people might want to purchase for the holidays seems to be vulnerable to snags in the global supply chain:

Here is an incomplete list of consumer goods that have been subject to backorders, delays, and shortages: new clothes, back-to-school supplies, bicycles, pet food, paint, furniture, cars, tech gadgets, children’s toys, home appliances, lumber, anything that relies on semiconductor chips, and even coveted fast food staples like chicken wings, ketchup packets, Taco Bell, Starbucks’ cake pops, and McDonald’s milkshakes (in the UK, for now).

“Most likely, there will be some shortages on specific products over the holiday season,” Seckin Ozkul, from the University of South Florida’s Supply Chain Innovation Lab, said. “So, if consumers know what they want to buy for their loved ones for the holiday season, now is a good time to act on it.”

until sometime next year. When buying online, it may be worth looking to see if local stores have a curbside pick-up option. (One helpful tool for this is Google Shopping, which can include information about where an item is in stock at nearby retailers.)

Another strategy is just to avoid online shopping altogether and buy items in stores, the old-fashioned way. Bigger chains like Walmart and Home Depot have the resources to charter their own cargo ships, and they seem less likely to be out of items. Best Buy, of course, is hoping that some people will consider paying $200 to secure access to in-demand products, though the company hasn’t shared which products that program will include.

Regardless of how customers choose to prepare, they shouldn’t assume that supply chain problems will be resolved before the holidays. Given how easily shortages compound other shortages, there doesn’t seem to be an end date in sight.