The name delta, meanwhile, comes from the WHO system, which is meant to simplify genomics for the general public. It gives names to related covid samples if it believes they may be of particular interest. There are currently eight families with Greek letters, but until there’s evidence a new sublineage of the first delta strain is acting differently from its parents, the WHO considers them all to be delta.

“Delta plus” takes the WHO designation and mixes it up with Pango’s lineage information. It doesn’t mean the virus is more dangerous or more concerning.

“People get quite anxious when they see a new Pango name. But we should not be upset by the discovery of new variants. All the time, we see new variants popping up with no different behavior at all,” says Brito. “If we have evidence a new lineage is more threatening, WHO will give it a new name.”

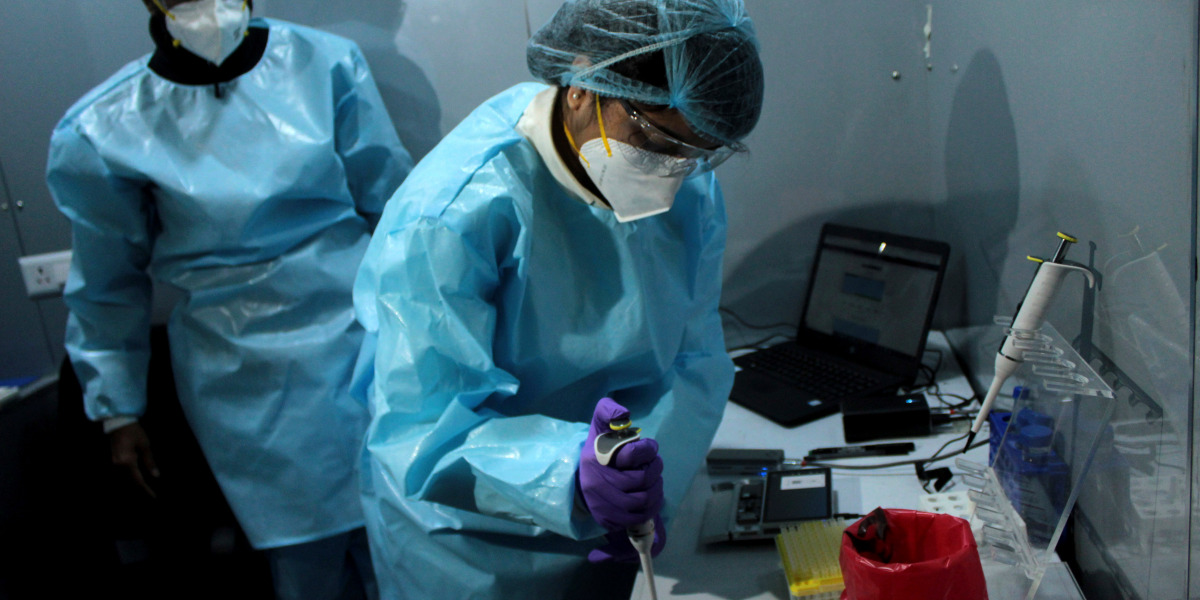

Tracking evolution

“For a genomic scientist like me, I want to know what variations we’re seeing,” says Kelsey Florek, senior genomics and data scientist for the Wisconsin state public health lab. “For the greater public, it doesn’t really make a difference. Classifying them all as delta is sufficient for communicating with policy makers, public health, and the public.”

Fundamentally, viral evolution works like any other kind. As the virus spreads through the body, it makes copies of itself, which often have small mistakes and changes. Most of these are dead ends, but occasionally, a copy with a mistake replicates enough inside a person to spread to someone else.

This week, scientists split delta’s “children” into 12 families in order to better track small-scale local changes. None of this means the virus itself has suddenly changed.

As the virus spreads from person to person, it accumulates those small changes, allowing scientists to follow patterns of transmission—the same way we can look at human genomes and identify which people are related. But in a virus, most of those genetic changes have no impact on the way it actually affects individuals and communities.

Genomic scientists still need a way to track that viral evolution, though, both for basic science and to identify any changes in behavior as early as possible. That’s why they are keeping a close eye on patterns in delta, especially, since it’s spreading so rapidly. The Pango team continues to split descendants of the first delta lineage, B.1.617.2, into subcategories of related cases.

Until recently, it had registered 617.2 itself plus three “children,” called AY.1, AY.2, and AY.3. This week, the team decided to split those children into 12 families in order to better track small-scale local changes—hence the total of 13 delta variants. None of this means the virus itself has suddenly changed.

“Especially at the margins, with these emerging variants, you are splitting hairs,” says Duncan MacCannell, chief scientific officer of the CDC’s Office of Advanced Molecular Detection. “Depending on how those definitions are crafted and refined, the hairs can split in different ways.”

What matters to the public?

It’s worth noting that not all variants with WHO nicknames are equally bad. When the organization gives a new family a name, it also adds a label telling us how worried we should be.

The lowest level is a variant of interest, which means it is worth keeping an eye on; in the middle is a variant of concern, like delta, which has clearly evolved to be more dangerous. Often, variants of interest are given that label because they share a mutation with variants of concern—they’re under surveillance.